I come to this blog carnival discussion wearing several hats: One as an online journal editor who publishes multimodal scholarship that integrates text, image, audio and video, but I also come to this as an English department chair knowing that our faculty members need models of support and reward for the development of digital teaching and research materials. I also come to this discussion as a graduate educator in terms of the obligation to prepare future faculty to both consume and produce scholarship in digital form and to be aware of the academic labor issues involved.

Sometimes I worry that in our roles as digital rhetoricians, we spend a lot of time talking to each other (preaching to the converted) when we need to help our faculty and administrative colleagues better understand what’s happening outside of the academy with regard to digital literacy practices, and to match that against what’s happening, or in many cases not happening, inside the academy, and address concerns about the future of digital scholarship and about sustaining a digital rhetorical ecology.

Our Nostalgia for Print

Think about a literacy moment in your own life, past or present…

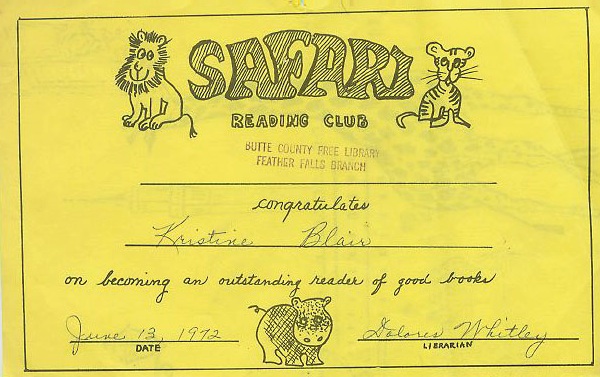

I include this image because I also come to this discussion as a scholar-teacher of a particular generation who grew up reading books. I grew up in a very rural area of Northern California called Feather Falls, a community where there was for a time a general store, a post-office, a school, and a library, and nothing more. The postmaster and the librarian were the same person. So books were my chance to escape that life—I even read the World Almanac; to this day, people will ask “How do you know that?”—and I owe this to my mother who was what Deborah Brandt has termed a “literacy sponsor,” teaching me to read, making sure that for every toy I received I also received a book, and encouraging me to participate in reading clubs. Today, I’m a type of literacy sponsor for my 81-year-old mom with tools such as Facebook, so in many ways, we’ve come full circle.

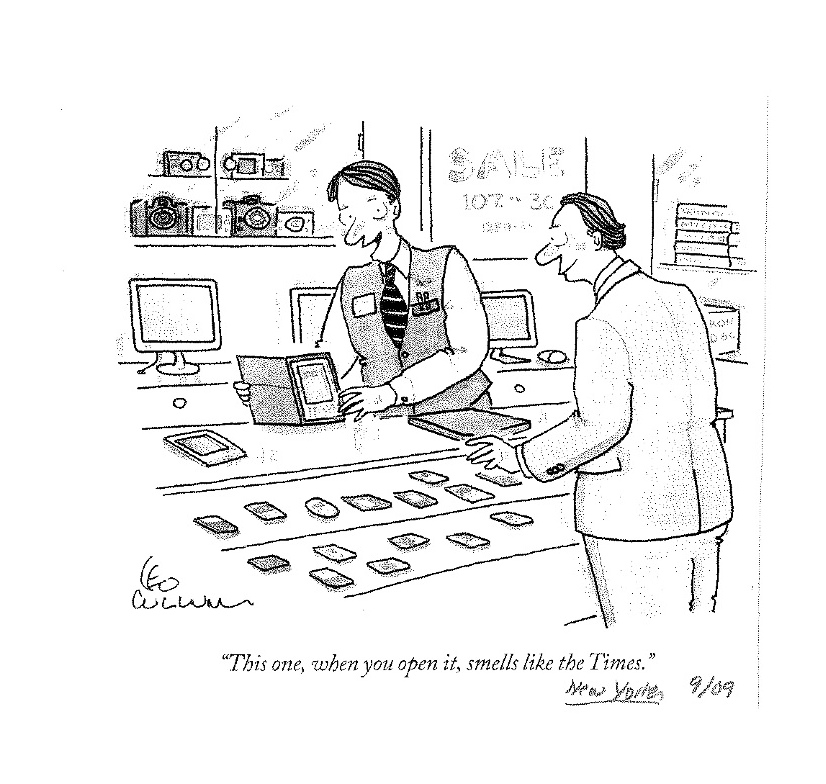

Despite these digital and generational shifts, there’s a certain nostalgia for many of us about printed books as much as there is for the words they contain; our memories of books have a lot to do with their materiality, their sensuality, and this cartoon from The New Yorker plays upon that:

I think I’ve made that transition in my own online reading practices and am about to update to a newer iPad. But what is gained and lost in the move from print to digital text?

False Literacy Binaries?

For some people, including James Tracy, Headmaster at the Cushing Academy, it’s more gain than loss. In 2010, the Cushing Academy, a college prep school in Massachusetts, began the process of dismantling its brick and mortar library of about 20,000 volumes for a digital library with kiosks and a number of different eBook readers to enhance access to vast amounts of information from across the disciplines. At the time, Tracy commented that

If I look outside my window, and I see my student reading Chaucer under a tree, it is utterly immaterial to me whether they’re doing so by way of a kindle or by way of a paperback.

Yet, for some it’s more loss than gain. Nicolas Carr in “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” and his later book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, laments the presumed impact of information overload and ecommerce on our ability to think critically:

The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds.

Carr acknowledges that his critiques are similar to Plato’s critique of writing in The Phaedrus, and that technology is an inherent part of our literate lives both past and present. But as Cathy Davidson notes in her more recent book Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention will Transform The Way We Live, Work, And Learn:

Pundits may be asking if the Internet is bad for our children’s mental development, but the better question is whether the form of learning and knowledge making we are instilling in our children is useful to their future…the answer more often than not is no.

The presumptions of a print/digital divide equally divide the academy, but here are some key definitional questions for us to consider as digital rhetoricians:

- when is a book a book?

- when is scholarship…scholarship?

- what does it mean to read, write, and research in a digital age?

Certainly, there are a number of relevant theories to describe the relationship between the print and the digital, between old and new media:

- Bolter’s remediation as the way in which electronic writing remediates, repurposes, and alters the conventions of the print book while maintaining some conventions of alphabetic literacy, implying that digital hypertext improves upon the linearity on print;

- Jenkins’ emphasis on convergence as the relationship between media to disseminate culture and ideology in a participatory system and;

- Lessig’s sense of the Remix as the creative borrowing and meshing of multiple media to create a read-write culture in which citizens use media to produce as much of that culture as they consume.

To get at some of our understanding of how these concepts may play out and the ongoing tension between the larger culture and the academy, I think a lot of the work from the Digital Ethnography project that Michael Wesch has developed with students at Kansas State is relevant, and while the viral nature of some of his work makes it familiar to many of you, it nevertheless provides a good reminder about the literate lives our students are living:

What’s explicit in much of Wesch, et al.’s video work is that there’s a gap between what students do with technology and what we don’t do with it, though I think it’s equally important that we not presume all students or all teachers for that matter have the same access levels.

Indeed, the common metaphor is that students are digital natives, ala Marc Prensky’s “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.” This is a particular cultural rhetoric of technology, and despite its frequent usage, we should view it as a false binary that reinscribes an us/them relationship and puts teacher-scholars, including those of us working in rhetoric and composition, computers and writing, the digital humanities, at a distinct disadvantage, suggesting everything’s changing, except us. But we are changing.

Our Digital Present and Future

Actually, we’ve made phenomenal progress in developing forums for creating digital scholarship, such as this video essay “This is Scholarship,” created by Katie Braun and Ken Gilbert and published in Kairos:

I actually reviewed this piece a couple years ago for the journal, and even for me it was a surprise to get a video submission and to reflect upon types of implicit criteria I applied as a viewer/reviewer to/of that video—now, such submissions seem natural, almost an expectation, for those of us working in this area, but they don’t just happen.

There’s admittedly an invisible labor issue with digital scholarship; how long do we think it took these collaborators to work on the video? How does that labor compare to print-based counterparts? Thus, another important issue is tenure and promotion, ensuring our documents are inclusive enough, valuing the publication of multimodal scholarship in online venues and recognizing the time and collaborative processes that so often comprise born digital texts. We have to ask how digital scholarship is being valued by the academy itself in terms of our incentive and reward systems, something for which our colleague Cheryl Ball has been a forceful advocate for change, using her own groundbreaking work as a model for others to follow, and something that’s been addressed by scholars such as Kathleen Fitzpatrick in her book Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy.

As Fitzpatrick notes:

Writing and publishing in networked environments might require a fundamental change not just in the tools with which we work, or in the ways we interact with our tools, but in our sense of ourselves as we do that work.

And maybe that’s the problem: Our own disciplinary culture remains so rooted in print ideologies that, as a result, such digital scholarly venues don’t yet exist. That’s why I believe that scholarly communities like the Sweetland Digital Rhetoric Collaborative, as well as the Computers and Composition Digital Press, are vital intellectual and ideological resources not only within our own field but also within the wide scope of the digital humanities.

Yet for me, the looming issue is training and exposure to digital composing processes within graduate education. We have to ask the same questions of graduate education that Davidson does with children above in the quote I included earlier. Do our graduate students understand what it means to be a digital rhetorician?

Graduate students have to the opportunity to experiment with multimodality through genres such as electronic portfolios and digital dissertations and need space within graduate seminars, preliminary exam processes and elsewhere in their teaching and research to learn code, design, and other elements of digital composing that our programs often fail to provide in a consistent way.

This is where I think we need to push harder to make such genres viable within English studies in general and rhetoric and composition in particular. For instance, we’ve been talking about the possibility of electronic theses and dissertations for over a decade, yet even when electronic submission is possible, it tends to be little more than a save a MS-word document as .pdf model. Some of it has to do with the academic labor issues I mentioned above, but it also has to do with policies and ideologies that presume a dissertation is at its best a single-authored print genre. The fact that our colleague Melanie Yergeau was able to complete a digital dissertation at the Ohio State University is major step in the right direction; how can we make such innovation the rule rather than the exception? This conversation is undoubtedly another step toward that goal as well.

Overall, in addition to grounding scholarship in multimodal composing processes to foster a digital rhetorical collaborative such as this, our field needs to look for ways to mesh technology with policy and ideology, to bridge the gap between what’s happening outside the academy and what’s happening inside to maintain our relevance in both realms, and support both current faculty and graduate students as the future faculty who will help us get there.

3 Comments

Kris,

Thanks for a thought-provoking post that ties some of the same issues I’ve been thinking about together. (Guess who I took that cue from?? 😉

We’ve been “doing” digital rhetoric with our undergraduates for years, and as faculty we do it (for tenure purposes, we hope) for a while as well, but while graduate students get to practice in their class assignments sometimes, they don’t often get the opp to make things for their comps and diss. Melanie is a great counter-example to that. (Two webtexts — both award-worthy — and a digital diss before she graduated? Awesome.)

At the Graduate Research Network this year, lots of folks asked the question about whether a digital diss was worth it. My answer is always someone cavalier: Someone’s got to take the chance; will it be you? It seems dumb to still have to say that — as if a digital diss or digital scholarship in general — a do-or-die proposition. Seems irrelevant in the bigger scheme of things. Except, doing back to Cathy Davidson’s quote: What disservice are we doing the world (yes, the world!) by not pushing for better rhetorical strategies in all our texts.

I look forward to taking up this conversation in my post later this week. Thanks for this week’s kick-off!

Oh, and here’s a link to Katie Braun and Ken Gilbert’s “This is Scholarship” piece in Kairos.

Cheryl.

I think there’s a negative cause-effect relationship here as well: If our graduate students do not have the opportunity to experiment with developing digital identities, and if they don’t have the chance to implement multimodality in their own research-writing processes and curriculum development, then our undergraduates won’t benefit from that experimentation and innovation in terms of literacy acquisition, and English studies (where so many of us reside) will continue to privilege composing models with diminished relevance both inside and outside the academy. Graduate students, as future faculty, should have the potential to become change agents.

And to what extent is digital rhetoric something we should all be accountable for in the undergraduate curriculum, not just in FYC or in tech comm and English education, but in the English major as a whole? Some programs have made that shift, but there are many that have not, and will not.

I really look forward to hearing your thoughts, Cheryl…thanks for the link; I linked to the video only and that worked fine initially, so not sure what got lost in translation, but I updated…

kris

Pingback: Digital Rhetorics: Simply Too Complicated a Phenomenon — Digital Rhetoric Collaborative