Review by Don Unger

Read about Session c13 on the C&W conference site.

Panelists

Jonathan Alexander, University of California, Irvine

Jacqueline Rhodes, California State University, San Bernardino

When I entered room 202 of Washington State University’s Center for Undergraduate Education a few minutes before 3:00 pm on Friday, June 6, I prepared to take notes for this review. My laptop’s battery was low, so I began looking around for an outlet. I don’t normally take notes on my laptop, but then I don’t normally enter a presentation intending to review it. What does it mean to review something? Does a review distill others’ ideas for general consumption? I thought taking notes on my computer would make it easier to do just that. I would address the main ideas in Alexander and Rhodes’ work and make it accessible for folks who weren’t at the conference or this particular session. Put simply, they approached the relationships among identity and agency as a process of (dis)orientation and demonstrated how others (humans and objects) help shape this process. Still, a simplistic review can’t capture the complexity of Alexander and Rhodes’ work.

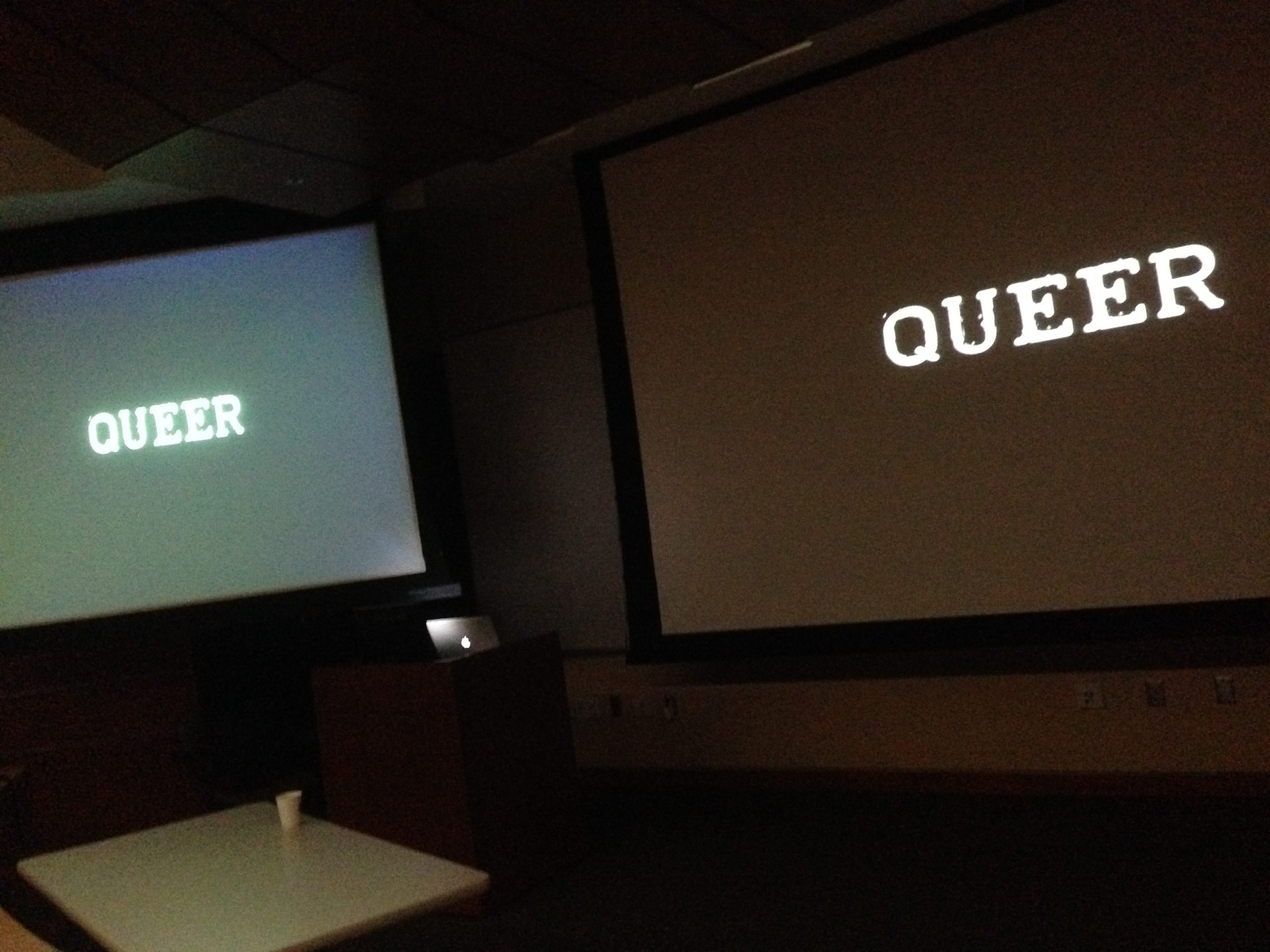

As I sit at home a week later and debate how best to represent their work, another strategy emerges. Instead of offering a review, maybe I can reenact a small part of the session and provide readers with a similar though less ambitious experience. Alexander and Rhodes billed “Techne: Queer Meditations on Writing the Self” as an installation, and the distinction between a presentation and an installation is an important one. The distinction pushes me away from representation toward reenactment. As I see it, a presentation offers the audience information: here is my analysis of the data. An installation presents an immersive experience: here is the way I’ve made meaning. Let me share it with you…

As I fumbled around looking for an outlet to plug in my laptop, Alexander and Rhodes set up their installation. For me, the scene looked something like this.

Interior. Lecture Hall.

An audience of largely middle-aged academics slowly enters a well-appointed room with tiered rows of tables and chairs that arc around a podium at the front. As the audience takes their seats, a projection screen suspended from the ceiling above the podium and the surround sound speaker system come to life. George Méliès’ Le Voyage dans la Lune fills the hall.

Audience Member: Is this that Smashing Pumpkins video? (beat) What’s that song?

Reviewer: “Tonight, Tonight”? (beat) I think it’s based on an old French film.

Audience Member: Hmm. I just see the Smashing Pumpkins video.

Reviewer: I think it was in the movie Hugo, too.

The reviewer fumbles with his computer.

Reviewer: It’s called A Trip to the Moon.

A trip to the moon. Orientation weaves through the installation, specifically the ways that technology exerts control over one’s orientation and reinforces power relations. In this case, Google reorients me in a disorienting situation. It helps me find answers for an audience member’s question, which in turn reorients me as a reviewer. As a reviewer, is it my job to help answer these questions, or at very least help reframe the questions others ask in relation to the installation? Was it then, and is it now? Even before it officially begins, before Alexander and Rhodes introduce themselves, I am subject to their installation’s (dis)orienting effects.

With hindsight, I realize that I was already part of the installation, and there’s so much to it that I cannot represent in the space of this review. Explication falls short, so I return to description, egging the reader on as if to say, “This part clarifies something.” As Jackie Rhodes and her laptop orchestrated an overlapping series of images and video clips on the projection screen, Jonathan Alexander chronicled his ongoing battle with the voice recognition software on his smartphone, teased out the connections among Paul Dourish’s work on ubiquitous computing and Sara Ahmed’s work on queer phenomenology, and discussed how long before Latour’s work, the ballet Parade explored the collapsing of subject into object. At times, the videos and script overlapped in clear or immediately accessible ways. For example, I remember Alexander describing the disorienting effects of technology as Rhodes projected a video of a child spinning in circles across the screen.

With hindsight, I realize that I was already part of the installation, and there’s so much to it that I cannot represent in the space of this review. Explication falls short, so I return to description, egging the reader on as if to say, “This part clarifies something.” As Jackie Rhodes and her laptop orchestrated an overlapping series of images and video clips on the projection screen, Jonathan Alexander chronicled his ongoing battle with the voice recognition software on his smartphone, teased out the connections among Paul Dourish’s work on ubiquitous computing and Sara Ahmed’s work on queer phenomenology, and discussed how long before Latour’s work, the ballet Parade explored the collapsing of subject into object. At times, the videos and script overlapped in clear or immediately accessible ways. For example, I remember Alexander describing the disorienting effects of technology as Rhodes projected a video of a child spinning in circles across the screen.

At other times, I had difficulty making connections among the layers of moving images and the script. My notes evidence this confusion. At such points, I turned from divining the installation’s deeper meaning to documenting what was said and projected. I imagine any trip to the moon requires a fair bit of holding on for the ride, and that’s how I’d think about those moments where I go into description here in this review, holding on.

Again, I cannot possibly represent all the twists and turns of our trip to the moon, but maybe this reenactment can orient and disorient a reader. In that sense, I’ve tried to provide things to cling to when disorientation sets in, such as a few details about the installation’s structure and content, but I’ve also sought to orient the reader as he/she/ze considers what Alexander and Rhodes offered. Toward the former, I would say that the installation demonstrated the continued importance of critique in discerning when one is affected by and affecting others. Toward the latter, Alexander and Rhodes’ installation queers such discussions about how humans and objects (dis)orient one another in a number of ways. I leave you with two. First, the installation’s complex structure created an experience that defies simplistic representation; it allows for or even forces multiple readings. Second, its (dis)orientation identifies queering as a largely underutilized method(ology) for investigating the relationships among humans and objects within Rhetoric and Writing Studies.

To experience some of Alexander and Rhodes recent work, check out the links below.

Alexander, Jonathan, and Jacqueline Rhodes. “Queer Rhetoric and the Pleasures of the Archive.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture 13 (2012): n.pag. Web. 14 June 2014.

Rhodes, Jacqueline, and Jonathan Alexander. “Queered in Technoculture.” Technoculture: An Online Journal of Technology in Society 2 (2012): n.pag. Web. 14 June 2014.

Don Unger is a Doctoral Candidate at Purdue University. You can follow him on Twitter @donunger.