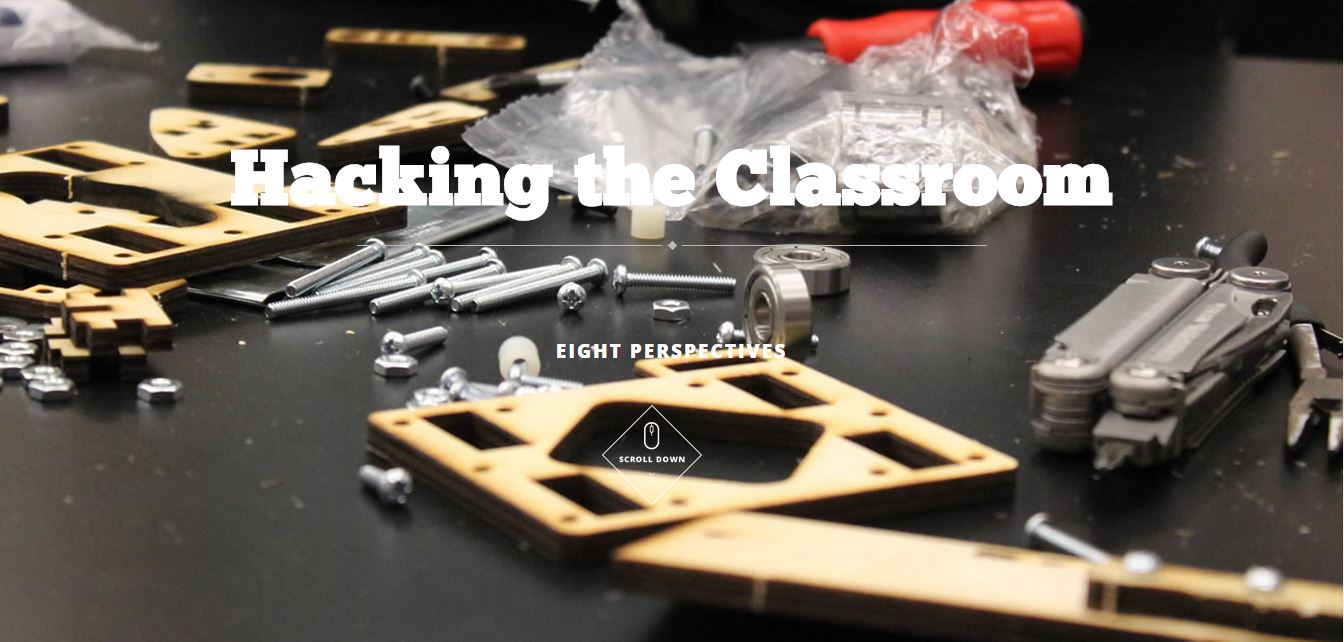

Text: “Hacking the Classroom: Eight Perspectives”

Authors: Jim Brown, Mary Hocks, Aimee Knight, Virginia Kuhn, Viola Lasmana, Elizabeth Losh, Jentery Sayers, Melanie Yergeau

Publisher: Computers and Composition Online

Publication Date: Spring 2014

If there was a 2014 year-in-review list for the Computer and Writing community, I would undoubtedly nominate the word “hack” as a top-of-the-list contender for the year’s most used (and mis-used) word. I’ll admit that I’ve often been bothered by the appropriation of the word “hack” to describe the process of re-thinking, remixing, remediating, or simply re-doing the ways that we teach writing or the spaces in which writing work happens. To me, applying the phrase “hacking” to these practices always just seemed like sexing up good teaching.

If there was a 2014 year-in-review list for the Computer and Writing community, I would undoubtedly nominate the word “hack” as a top-of-the-list contender for the year’s most used (and mis-used) word. I’ll admit that I’ve often been bothered by the appropriation of the word “hack” to describe the process of re-thinking, remixing, remediating, or simply re-doing the ways that we teach writing or the spaces in which writing work happens. To me, applying the phrase “hacking” to these practices always just seemed like sexing up good teaching.

So, I approached my reading of the multi-authored webtext, “Hacking the Classroom,” published in the most recent issue of Computers and Composition online, with a heavy dose of skepticism. I initially wondered how these eight authors – ranging from emerging practitioners, established scholars, and even an undergraduate student – would use the term “hacking” in a way that wouldn’t seem like just another hip label for “good pedagogy.”

Yet the eight pieces included in this webtext convinced me that hacking should ultimately be a form of questioning. Here’s the key thing I learned: hacking should really turn conventional practices inside out to reveal both limitations and affordances. I can see now that when we “hack” spaces, when we “hack” scholarship, when we “hack” the academy, when we “hack” definitions of writing, and yes, perhaps above all, when we “hack” classrooms, we’re not just re-building; we’re actively resisting stagnation in our own and our students’ ways of looking at composing in the 21st century.

In this review, I’ll offer some of the highlights from the eight different segments of the webtext. I read this webtext as one linear series of articles because the webtext is organized in a long, vertical scroll; I enjoyed the fluid reading experience of moving from one author’s segment to the next. However, other users may find it more enjoyable to read the pieces out of order; clicking on an author’s name in the top menu will instantly take the user to any of the eight pieces.

In fact, the alphabetical orders of the authors’ names suggests that the webtext can (and perhaps should) be read in any way the reader chooses. Plus, in the introduction, Mary Hocks and Jentery Sayers cite inspiration for the webtext from the format of THATcamp, “unconferences” devoted to developing panel discussions and workshops based on the participants’ expertise and interests. Therefore, the webtext really strives to start conversation by providing a large frame for discussion, and allowing each author to apply that frame in a number of different contexts.

I’m going to do my best to keep this review short, but I find as I’m writing this review myself, there’s just so much to discuss and explore here! This is a very short list of the moments I found interesting or that I’d love to think more about:

Brown:

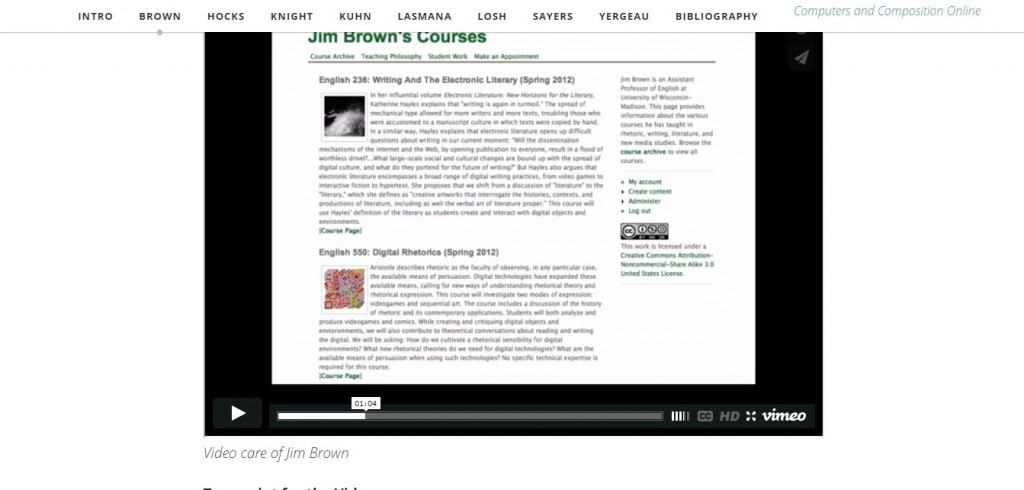

- Brown’s contribution is a short video that describes his motivation for making his classroom part of what he calls “the year of computational thinking.” His exigence is twofold: the need for students to develop greater digital literacy and the increasing need to make the value of the physical classroom space just as valuable as the online classroom space. Brown recognizes the value in online learning, but he states that they are not “the magic bullet” to educational problems. “Hacking the classroom” by thinking of it as a studio and workshop space, can be one way to explore its affordances more clearly.

- Perhaps my favorite part about Brown’s video segment of the webtext is his ending: hacking the classroom is not just something teachers can do, but that students can do themselves. I think this is a powerful statement; by asking students to take the agency in the classroom, they too can resist, question, and make changes to a space in which they may not necessarily feel immediately or intrinsically empowered. Asking students to create within the classroom space, as Brown does, responds not only to the external exigencies that Brown points out, but also the exigence of students in the classroom space itself.

Hocks:

- Hocks discusses her classroom assignment of asking students to record sonic soundscapes and to reflect on the experience of recording those soundscapes. Hocks makes the arguments that soundscapes offer students the opportunity to see that sound is an intrinsic part of our environment. Paying attention to how sound functions and what role it plays helps students become more rhetorically savvy. An assignment like Hocks’s is totally unfamiliar to me and I wish I could have seen materials like the assignment instructions to get an even clearer sense of how students approach the task. Making ambient sounds something more visible and clear does, indeed, seem to be a really exciting form of resistance, but I wonder how students responded to the assignment and how they would interpret it.

Knight:

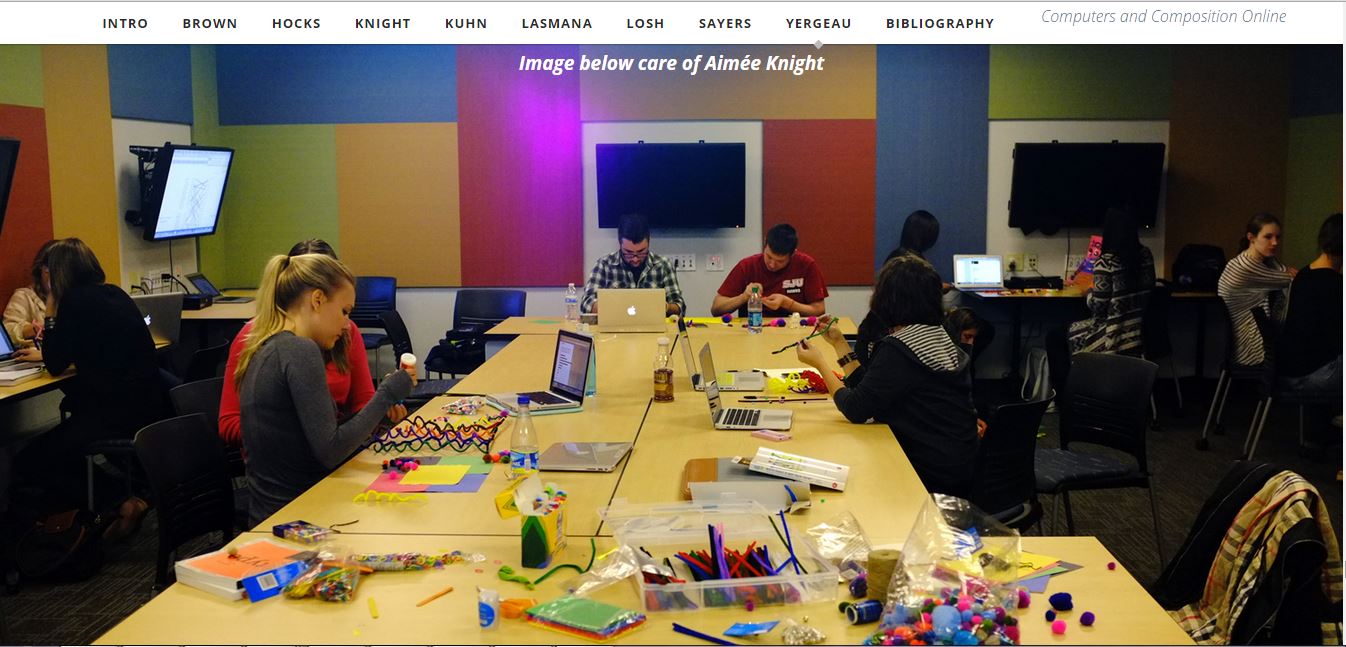

- Knight shares how her institution, St. Joseph’s University, has facilitated her class’s efforts to make the classroom a space that can be arranged and re-arranged to promote flexible learning spaces. This piece evoked some serious jealousy in me! It’s amazing to see how instructors like Knight an leverage resources to turn theories about learning and spaces into a reality. This piece inspires me to think more about how to disrupt my students’ own habits and practices in learning spaces, to facilitate the kinds of interactions that we know can promote collaboration.

Kuhn:

- As a graduate student, I was really glad to see Kuhn bring up the challenge of working with graduate pedagogy to promote multiliterate thinking! Much of the literature on “Hacking” the classroom focuses on the undergraduate experience, but Kuhn suggests that there’s still plenty of “hacking” that needs to be done to re-think a lot of assumptions about graduate education, including linear alphabetic text as the primary means of publishing tenure-worthy scholarship. Kuhn’s list of “don’t’s” for teaching at the graduate level ultimately shows the need to make one’s individual theories and ideas transparent, so that both student and instructor can communicate more clearly.

Lasmana:

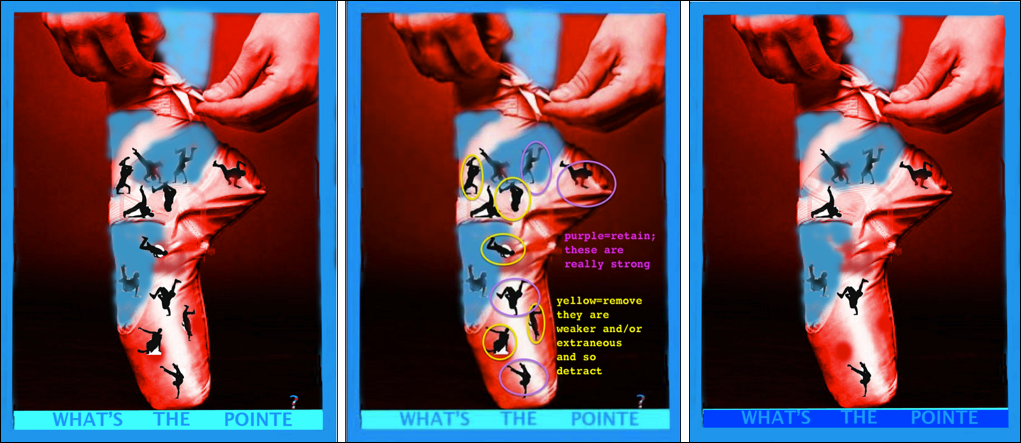

- Lasmana is one of Kuhn’s former students, and she does a great job of showing what she learned in Kuhn’s classroom and how she applied her knowledge of assemblage and remediation to her own work. Lasmana’s presence in this webtext is one of the real strengths here; it’s rare that we get to see an undergraduate student talk about her own work and apply what she learned in a scholarly context. Lasmana provides a lot of compelling reasons for including the kinds of assignments that Kuhn discusses in her own webtext, though Lasmana’s contribution could stand alone as a reflection on the value of developing multimodal literacies for re-thinking humanities scholarship.

Losh:

- Losh perhaps offers one of the clearest definitions of a “hacktivist” pedagogy in the entire webtext, so I was grateful to get to see a very direct expression of what it means to “hack” the classroom.

- Losh’s “to-do” list for encouraging a hacktivist pedagogy made me laugh out loud precisely because she makes very visible the problems with applying a set of practices in broad strokes. By suggesting that teachers both “Teach Code and “Don’t Teach Code” makes very visible the importance of being an instructor aware of the contexts of her classroom and the potential for various practices to either be disruptive (or not) in various classrooms.

Sayers:

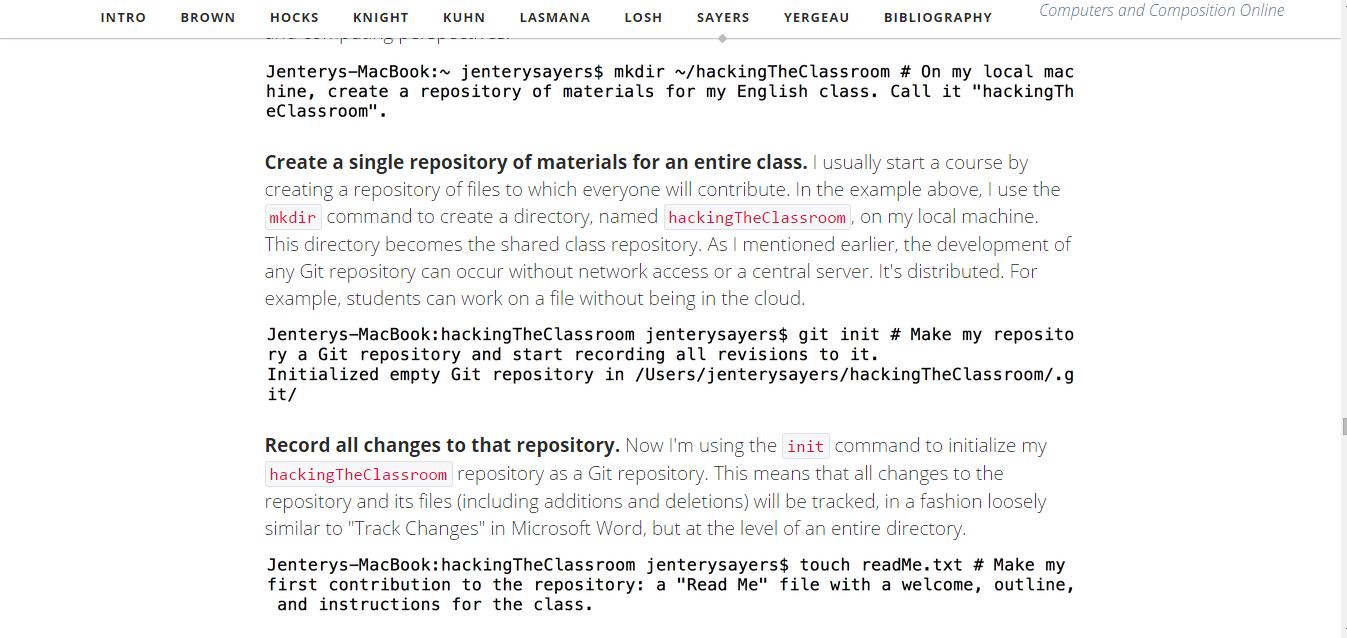

- As someone still learning the ropes of reading code, Sayers’s contribution proved the most challenging read, primarily because much of it is written as a demonstration of how he uses Git, a version control and source code management system, in his writing classroom. He makes the argument that instructors should consider using Git, not as a way to bring the sciences to the humanities, but as a way to support learning objectives related to collaboration and critical thinking.

- The final point of Sayers’s contribution is, in my mind, the strongest: a technology like Git facilitates sharing and individuation at once, practices that we want to encourage in any kind of writing class context. It can be challenging to simultaneously emphasize the value of individual contributions while promoting collaboration and the ways that Git make visible the changes that users make to each other’s codes and contributions can emphasize the value of creativity and teamwork.

Yergeau:

- I appreciate that Yergeau’s work typically brings in an engaging narrative, and this piece is no exception. Yergeau picks up on the argument that the “hackathon” uses the problematic language of “disability telethons” to exclude disabled coders and writers rather than include them in the process. She tells the shocking story of hackathons devoted to “curing autism” that include not a single autistic individual as part of the hacking and coding process.

- Yergeau’s argument that disability should be treated as something that needs to be included rather than fixed is crucial; this, to me, is a prime example of not only “hacking” the language of hackathons themselves, but “hacking” conceptions of disability at large and discouraging rhetorics of normalization.