Panelists:

Kevin Brock, University of South Carolina

Ashley R. Kelly, Purdue University

Annette Vee, University of Pittsburgh

James J. Brown Jr., Rutgers University

The three papers featured in this panel – Kevin Brock and Ashley R. Kelly’s “Rhetorical Genres in Code”, Annette Vee’s “What Happens to Rhetoric When Code is Law?”, and James J. Brown Jr.’s “Rhetorical Dissection and Tinkering in the R-CADE” – each examined a specific modality of digital rhetoric while seeking to engage code at various levels of abstraction. The focus of the panel seemed to congeal around the idea that code itself can be persuasive in many contexts, including programming, law, and design.

Brock and Kelly’s “Rhetorical Genres in Code” asked us to consider the hypothesis that code is a persuasive genre in the same way that traditional writing is. Their talk focused on an analysis of rhetorical activity within the context of coding communities and sought to attend to the different genres that codes and coders use to negotiate and persuade one another. They argue that code genres are particularly interesting since it is there where one can discover the persuasive effect of codes. Much of the talk described their case study that looked at a group of software projects, including “spam control modules for the Drupal content management system (specifically, CAPTCHA, ReCAPTCHA, Captcha Riddler, and BOTCHA).” Brock and Kelly examined the iterations of those tools along with particular coding techniques to illustrate how coders persuade one another via code development. The notion that code itself maintains persuasive rhetorical effects as a genre is an interesting one worthy of further consideration. Indeed, the topic seems to be at the center of digital rhetoric as a subject. Just how is code rhetorical? Brock and Kelly will hopefully contribute further to answering this question in their future work.

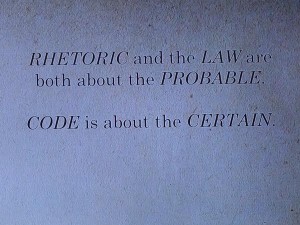

Annette Vee’s paper, “What Happens to Rhetoric When Code is Law?” drew on the work of Lawrence Lessig and focused on legal code and computer code, arguing that each are engaged in a certain push-and-pull or a type of reciprocal relationship. Vee discussed examples where legal code can constrain or afford computer code (and vice versa) and examples where problems might arise for democracy and the rights of citizens who are caught in between. Vee asks “if the deliberation, passage, justification, codification, and implementation of laws has always been a domain for rhetoric, what happens to rhetoric when computer code is effectively inseparable from law—when code is law?” This is an interesting point and it would have been nice to hear more about some of the previously existing literature on this topic (if there is any). Yet, computer code, Vee tells us, can also open space for deliberation and spaces of rhetoric. Her presentation analyzed this new space of rhetoric by working through several examples of computer and legal code (Common Terms, Creative Commons, and Common Accord). Each of these, she claimed, offer new and exciting possibilities, and also challenges. Vee argued that rhetoricians should give special attention to computer code since it is becoming inseparable from legal code. Overall, the presentation was an interesting one. The potential for rhetoricians to engage the work of legal scholars seems timely and appropriate.

James J. Brown Jr.’s paper, “Rhetorical Dissection and Tinkering in the R-CADE” offered an analysis of a hacked Game Boy. Specifically, he asks whether or not rhetoricians have anything to say about hardware instead of only software and code. His answer seemed to be an emphatic “Yes!” while arguing that rhetoricians should pay attention to the specific components of technological systems. He offered a close analysis of a digital artifact – the Game Boy Camera – to show how rhetoricians might focus on detailed discussion of the technological objects themselves while finding new and exciting ways to engage their design and historicity. The presentation was entertaining and audience members were able to pass around the Game Boy Camera to take selfies with it. Brown reminded us that the camera swiveled its head to take selfies, a technique that was ahead of its time in 1998. The Rutgers-Camden Digital Studies Center was also discussed, specifically the Rutgers-Camden Archive of Digital Ephemera (R-CADE), an intriguing sounding collection of digital artifacts collected for research purposes. The R-CADE seems to encourage the hacking of these old gadgets, and judging from the Game Boy Camera analysis presented, this is a worthwhile pursuit. The presentation was fun and it was nice to pass around a tactile object to get a ‘hands on’ feel for the technology.

In summary, Session 4 was a highly engaging and useful one for helping to stimulate discussion about the various modalities of digital rhetoric and the ways that code can be engaged at multiple levels of abstraction. It is clear that computational code, legal code, and design can all inform the work of digital rhetoricians in new and exciting ways.