My love affair with Castlevania has been long in the making. I like to tell people that Castlevania: Symphony of the Night made me an 18th century scholar, since it takes place in 1797 and features prickly harpsichord music composed by the marvelous Michiru Yamane. Symphony of the Night plays up a perfect contrast of creepy and polite that I would later find in 18th century gothic novels. I didn’t learn until very late in my career as a graduate student in English that video games are a viable area of study, until I read Rhetoric/Composition/Play through Video Games. The fanboy in me found himself vindicated at last.

I have since grown interested in bringing video games into the classroom, along with the problems and challenges they can bring with them. There are the logistical challenges: video games and gaming consoles are costly, nor can an instructor assume that the class is already familiar with gaming culture. Castlevania in particular caters to an entrenched and specialized fandom: it’s a gothic game, but not necessarily a horror game like Silent Hill; it’s an action-adventure, but not necessarily a puzzle-solving fantasy like Zelda. Even the newer games feature frequent winks and nods, hints intended for an audience steeped in the franchise’s lore.

There are also the ideological challenges video games pose, challenges that can lead to provocative discussion. Many games presume a heterosexual male audience, an imbalance that Anita Sarkeesian and many other video game critics have attempted to redress for years. It is for this reason that I think Castlevania, despite its specialized fandom, illustrates how deep the gender divide in the gaming industry runs.

The gender polarization of gaming fandom is well documented. Rebekah Shultz Colby, for instance, highlights that same kind of division in her first-year composition class taught through (and as) World of Warcraft. Reflecting on the success of her class which used the MMORPG as its platform, Colby observes that her class “segregated” along gender lines. Male students banded together, sharing hints with one another, and, for the most part, leaving the female students to fend for themselves (136). Castlevania‘s deliberate turn towards traditional masculinity typifies a similar shoring up of a particular kind of gaming community against perceived encroachment.

Some background on the Castlevania series as a whole would help establish the franchise’s record for attempting to portray strong female protagonists. I base my information here on the timeline laid out in the Castlevania Wiki. The first Castlevania game, released for the NES in 1987, establishes the basic narrative structure: Simon Belmont embarks on a quest through Dracula’s castle to slay Dracula with a holy whip that has been passed down through generations of Belmonts before him.

Every 100 years, Dracula returns from the grave, and every 100 years a Belmont descendant answers the challenge to defeat him. In Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse (released for the NES in 1989), Trevor Belmont enlists the aid of a mage named Sypha Belnades, beginning the tradition of the male Castlevania protagonist backed by a secondary female character.

In later years, the franchise would experiment with female protagonists, sparingly. Sonia Belmont, the heroine at the center of Castlevania Legends (Game Boy, 1998) presents one such prominent example: the Konami developers claimed her as the matriarch of the Belmont clan, establishing a strong female presence in a privileged place in the series’ canon.

Years later, though, Konami rewrote its own canon by making Leon Belmont the clan’s founder instead in Lament of Innocence (PlayStation II, 2003), replacing their previous matriarch with an angsty male lead.

Perhaps the franchise’s boldest move in creating a strong female protagonist—one who needs not share her stage with a male counterpart—would later come in 2008 with Order of Ecclesia. This installment was one of the last games in the Castlevania franchise directed by Koji Igarashi. Igarashi worked on numerous Castlevania games, including the iconic Symphony of the Night. Unlike its predecessors, Ecclesia usurps the typical Sypha Belnades role by making this magic-wielding female support character the hero in her own right.

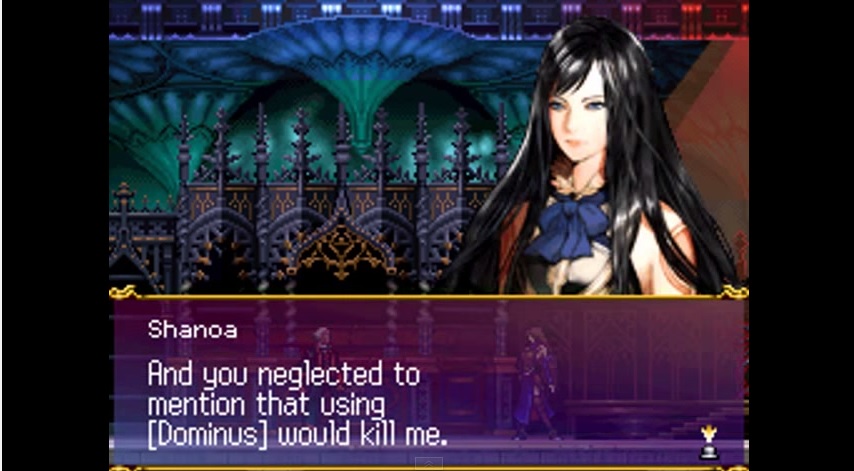

Ecclesia‘s main character is Shanoa, a witch who has been robbed of her memories and emotions. In many ways, Shanoa’s is a story of traumatic self-discovery, a painful process of realizing that Barlowe, her mentor in her order, has been using her all along to retrieve Dominus. The Dominus glyph would seal Dracula in slumber forever, but destroy its user. It turns out that Barlowe concealed that last potentially vital bit of information:

So Shanoa must turn against her old mentor and destroy the vampire by herself. Igarashi’s team stages Ecclesia in a Victorian setting, designing Shanoa with a daring backless dress, and equipping her with a system of glyphs that involve absorbing enemies’ powers directly into her body, where she can store and release them as attacks. Igarashi claims he decided on Shanoa as the heroine because his fans had been “requesting a female lead.”

In 2014, Konami released Mirror of Fate, directed by Jose Luis Márquez after the art style introduced by Hideo Kojima in Castlevania: Lords of Shadow in 2010. David Cox, the Lords of Shadow producer, billed this turn in the series as a “reboot” of the franchise, hoping to make the game more mainstream. Retelling the interrelated stories of Simon Belmont, Trevor Belmont (who later becomes Alucard), and Gabriel Belmont (who later becomes Dracula), Mirror of Fate weaves a rather baroque tale of square-jawed, musclebound knights, each only superficially different from the next. They each have the same attacks, the same build,1 and the same paternal anxieties. This “rebooted” version of Simon sets out to destroy Dracula because he’s convinced that Dracula killed his mother, but along the way he finds out that Alucard is really his father Trevor, who left when he was just a boy to destroy Dracula himself, but never returned. Trevor himself was Gabriel Belmont’s son back before Gabriel became Dracula, and Dracula, right after killing Trevor, realizes this a moment too late and preserves Trevor’s life by vampirizing him, etc., etc., etc.

We’ve met these fatherless men before in countless stories; Shanoa, even without her emotions or memories, has a more compelling story than any of the new Belmonts. The only female characters in Mirror of Fate are an unnamed succubus, the vampire Carmilla, Gabriel’s wife, and Trevor’s wife. The succubus and the vampire appear only as eroticized monsters; the two wives appear only as accessories for their husbands. Gabriel’s wife, also unnamed, bids Gabriel farewell in the game’s prologue:

While Shanoa’s mile-long legs and daring décolletage suggest that female power can only come with sexuality—a problematic trope in its own right—the series’ attempts to explore female characters shows the tantalizing possibilities it could have attempted if its art direction had chosen a different audience. However, rewriting its own canon, Castlevania opted for a particular kind of male gamer over all others. The alluring witch has been replaced with more whip-toting jocks who eclipse all female presence.

With its long history and polarized gender iconography, the Castlevania series can present teachers with a compelling case study to demonstrate the systemic nature of GamerGate in the classroom. By showing how these politics play out not only among fandoms but also among designers, the franchise dramatizes many of the anxieties GamerGate claims to react against, and the ways these anxieties appear when games tacitly cater to them. In this way, we as teachers can use the Castlevania series to consider, as Heather Lang and Paula Miller point out in their CFP for our Blog Carnival, how “instructors [can]capitalize on games as a means for teaching for social justice“. While contextualizing these games might require some additional work for anyone wishing to teach with them,2 both illustrate the ways in which games emerge not only as products of politics, but as embodiments of them.

Works Cited

Colby, Rebekah Shultz. “Gender and Gaming in a First-Year Writing Class.” Rhetoric/Composition/Play through Video Games: Reshaping Theory and Practice of Writing. Ed. By Richard Colby, Matthew S. S. Johnson, and Rebekah Shultz Colby. Palgrave Macmillan: 2013. Print.

1. TVTropes.org applies the Walking Shirtless Scene to Gabriel, who wears only “his Badass Longcoat and trousers, exposing his glorious man-abs”, as well as Simon Belmont’s rather pectoral barbarian getup..

↩

2. While the Castlevania Wiki features a thorough timeline of all the games, the video Castlevania Retrospective on GameTrailers.com recounts the same narrative, and might be a more student-friendly way to present the game’s multi-tiered backstory while focusing on the game’s recurrent tropes. Since both Ecclesia and Mirror of Fate are Nintendo DS games, it wouldn’t be feasible to ask students to purchase both the games and handheld consoles themselves. A less expensive alternative would be to locate one of the numerous playthroughs of both games, many of which can be found on YouTube.↩