After returning to formal studies of writing after several years away, I realized that bots have begun to do a lot of on-the-ground writing work. While SmarterChild on AIM was fun to interact with way back in my early online life, my recent work as a content writer for a tech company informed me that bots are being used for a wide range of tasks, such as generating social media posts and automating messages to create sales contacts with minimal human effort. My hiring manager showed me several high-powered bots, but I took note of the free service dlvr.it, one function of which routes RSS feed updates to major social media platforms.

A Bot that Delivers

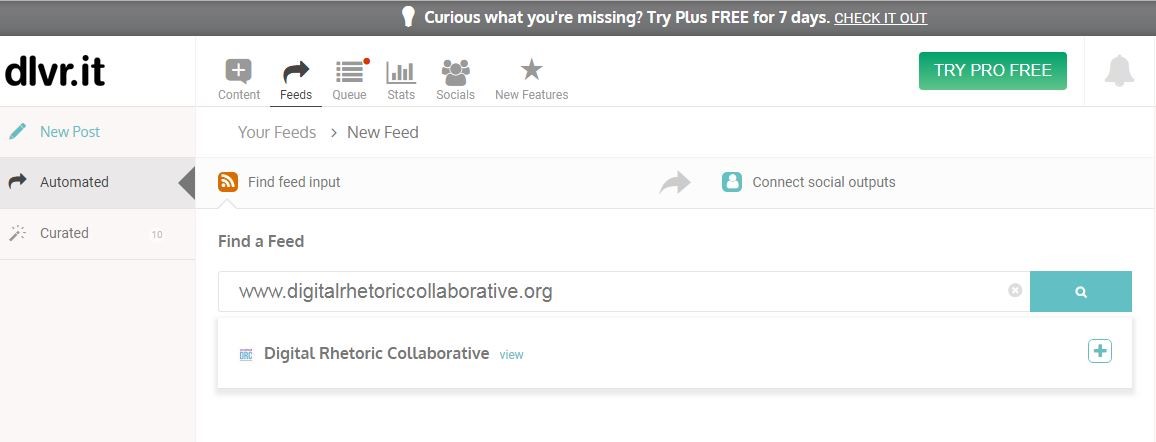

If I want to curate my Twitter feed so that a specific audience, for example potential academic employers, think that I am abreast of the latest in digital rhetoric, I would traditionally have to comb through the journals, sites, and blogs and share or create social media posts for each of the articles. To save time, however, I can go to dlvr.it and automate all of this through those publications’ RSS feeds. All you need to do is log in, click on “Feeds,” and then click “Add New Feed.” From here you can search for any website or key term, and it will populate a list of the closest matches. To test this out, I recently searched for the Digital Rhetoric Collaborative, and it populates their website.

Once I have added the DRC to my dlvr.it feed, it will begin importing posts into the social media accounts I allow it to access. You can even set a delay on when to share new items, which increases the perception that you have read and digested the contents of whatever post you are sharing. For those using the free service, however, the dlvr.it link remains on the post, which does give some indication how it was shared.

The Ethics of Bots as Ghostwriters

Ghostwriting is classically understood as the sale of Authorship rights to a client who will publicly claim the words. What interests me, however, is that bots function very similarly to ghostwriters in terms of hiding the labor involved in creating a piece of writing. In Ghostwriting and the Ethics of Authenticity, Knapp and Hulbert address this potential for misleading readers:

On this ethical terrain, one encounters concerns and questions of several varieties. The most apparent is the fact that the role of a ghostwriter is, by definition, not transparently evident to readers or hearers. For this reason alone, the practice is frequently condemned as an intent to deceive. (8)

Similarly, use of bots in Social Media (SM) works by mimicking human activity. For example, my dlvr.it service posts about 3-5 times per week under my Twitter and LinkedIn accounts, and those posts often see upwards of 50 impressions and frequently elicit engagements. Without having to read and evaluate each of the articles populated in my feed, I can set a bot to channel articles of concern to my field directly to my social media accounts. This is the same operation as using a ghostwriter to craft corporate announcements or write political speeches: I take the credit for written work someone or something else has done. But how ethical is this?

Knapp and Hulbert use a series of six questions to help readers consider the ethical implications of specific instances of ghostwriting, which I will replicate here to discuss potential ethical issues with the use of bots in our social media profiles.

Is it ghostwriting?

Yes, my social media brand gathers the impressions and engagements separately from those recorded in dlvr.it’s data. Compare the following analytics reports from dlvr.it and Twitter respectively to see the benefit I gain from work generated by dlvr.it.

Why are ghostwriters involved? What alternatives are available?

Keeping current with all of the research in our field is tedious work. The alternative to using bots to curate our digital professional identities is clearly to post everything manually, but time and financial constraints often forbid this. For graduate students and contingent academic labor, especially, time and funding are not allocated for us to be so heavily involved in the constant reading and promotion of new methods or theories in our fields. Nevertheless, we contingent laborers benefit the most from building these SM identities that support our job materials in demonstrating our stake in academic matters. A free bot service then provides an excellent resource to bolster our academic and pedagogical identities within our material realities of coursework, teaching, preparing, researching, comping, dissertating, writing job materials, shopping publications, and fighting for funding.

Whose interests are at stake in these projects?

For a SM profile, the account creator’s interest is almost exclusively at stake. I have used Twitter and LinkedIn to develop a professional persona, catering largely to my academic interests, and I have done this by live Tweeting conferences to populate my Twitter followers with other academics. While I cannot be sure who else uses these bot services, as I cannot access their systems to verify, I have noticed that many academic publishers engage with SM posts that involve their books or series even if they were not tagged in the post or following the particular account that posts.

What consequences may result from a decision to use a ghostwriter?

The basic consequences are that SM posts will reach a wider readership. By posting topics from blogs about writing and digital rhetoric and gaining reactions from those posts, searches for these topics in SM platforms are more likely to bring my posts to new readers. By increasing this readership, I intend to appear as a leader in my field who is frequently engaging in academic pursuits on public SM platforms.

What principles or duties are at stake?

As a rhetorician thinking about my own ethos in my SM posts, my use of bots bolsters my position as someone who can operate in current modes within SM and who knows what content will be useful in my future endeavors. At the same time, I know that even though dlvr.it arranges to post to my account for my gain I am ultimately responsible for all of the content and any misleading information I may give my readers.

How might the ghostwritten work affect the personal authenticity of the client?

Because the dlvr.it link remains on the free service posts, there is little reason to doubt the authenticity because the link is readily apparent to readers. If I were to remove that link by paying for the service, however, claims about my intent to deceive could then be leveled against me, arguing that I have failed to be authentic or transparent in my use of the bot service.

While Knapp and Hulbert’s list does not exhaust the questions pertaining to the use of bots and other forms of AI in rhetorical spaces, I believe that their questions open up a dialogue that we can all continue to ask of various forms of AI we encounter on a daily basis. I think it’s important to remember with bots, just as with ghostwriters, that invisible labor always poses a threat to the credibility of a message – without proper thought regarding the ethics of the practice, such use could easily harm our standing as credible speakers, writers, and thinkers.

Works Cited

dlvr.it. app.dlvrit.com/login. Accessed 29 March 2018.

@GrimmProspects. “Digital Rhetoric, Surveillance Studies, & Health.” Twitter, 29 March 2018, 8:03 a.m., twitter.com/GrimmProspects/status/979373483166593024.

@GrimmProspects. “#SatanInAPoncho.” Twitter, 9 October 2014, 7:01 p.m., twitter.com/search?f=tweets&q=%23Sataninaponcho&src=typd.

Knapp, John C. and Azalea M. Hulbert. Ghostwriting and the Ethics of Authenticity. Palgrave MacMillan, 2017.

Twitter Analytics. Twitter, 30 March 2018, analytics.twitter.com/user/grimmprospects/tweets.