As someone who teaches a variety of academic, technical, and multimodal writing classes, I have drawn influence from a number of design studies sources. Texts such as Ellen Lupton’s Design is Storytelling, Carl DiSalvo’s Adversarial Design, Sasha Costanza-Chock’s “Design Justice,” and Mario Gooden’s Dark Space have had profound impacts on how I view design as an important part of rhetorical composing. However, I don’t know if I have found a line in any of these texts that has lingered with me more than when, in his handmade zine, Garnett Hertz claims,

“Design can be how to punch Nazis in the face, minus the punching”

(Disobedient Electronics).

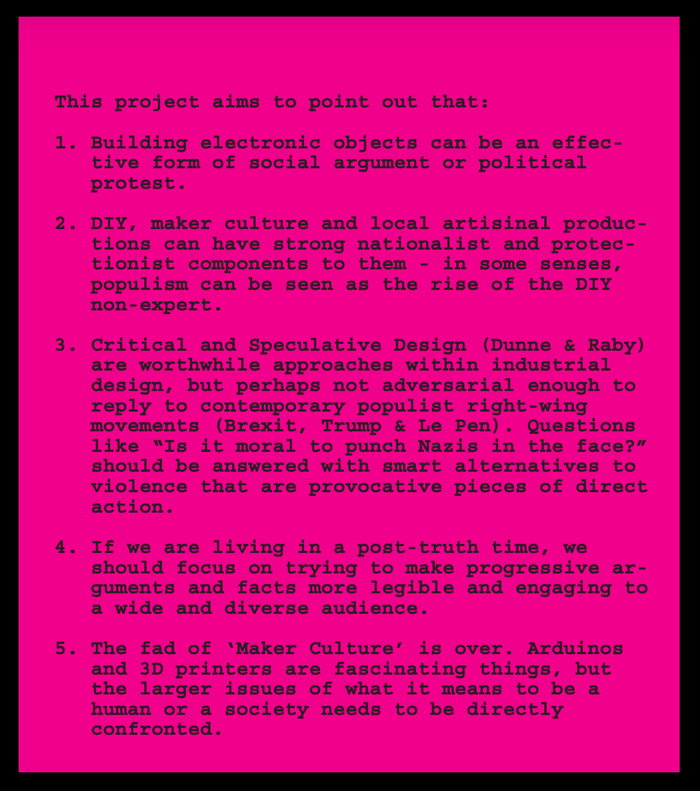

To be clear, Hertz isn’t advocating for violence, and neither am I. However, Hertz’s Disobedient Electronics: Protest was meant to be a disruption within the critical making and industrial design discourse communities. And, I will argue, in the brief space I have here, that this zine offers us, as writing and rhetoric scholars, a useful case study for considering how disruption fits into a conversation on design and social justice.

Disobedient Electronics is a text that disrupts conventions of academic writing. Its form blends together traditional D-I-Y methods and aesthetics with the conventions of an academic edited collection. It exists both as a limited run of 300 print copies which were distributed for free and as a website or pdf. Hertz describes the project as “a limited edition publishing project that highlights confrontational work from industrial designers, electronic artists, hackers and makers from 10 countries that disobey conventions” (disobedientelectronics.com).

In the introduction, Hertz tells us that he drafted the call for submissions the day after the 2016 election. Wanting to compose a text that responded to the election of Donald Trump, Hertz circulated a call for electronic media projects that rhetorically address issues such as “the wage gap between women and men, the objectification of women’s bodies, gender stereotypes, wearable electronics as a form of protest, robotic forms of protest, counter-government-surveillance and privacy tools, and devices designed to improve an understanding of climate change.” This is where his theory of design—as punching Nazis, without the punching—comes into play. It was designed as a means of disrupting a stagnant discourse by pushing design scholars toward more direct forms of public engagement.

One such project, the Abortion Drone, was used to fly abortion medications to women awaiting them in countries where they are illegal. The first flight, in 2015, launched from Germany, flew across a river, and landed on the banks Slubice, Poland. Immediately after the drone landed, two women quickly took the medications before German police crossed the border and seized the drone.

Most of the projects in the zine are not as potentially controversial nor do most involve the level of risk the Women on Waves activists are taking to deliver access to safe abortions. However, they are all designed in such a way to disrupt discussions surrounding social justice issues. Other examples include: The Device for the Emancipation of the Landscape, a massive sound canon used to project natural sounds “into sites of colonial, social, or ecological interest” (53), Phantom Kitty , a device which floods internet browsers with random data to resist surveillance, and the Dissenting Jabots (shown in first photo above) which are designs for electronic neckwear inspired by the collar Ruth Bader Ginsburg wears when dissenting from her Supreme Court colleagues.

Disruption in Design Advocacy.

In “The Rhetoric of Disruption,” Meg Worley provides a genealogy of the word “disrupt,” looks at the problematic ways in which it has been used in tech industries, and considers how it might be used more effectively within the Digital Humanities. According to Worley, much of Silicon Valley and technology industries define disruption as using new products

“as the pretext for a change in business models, a change that frequently leaves users worse off. At the same time that it is creative, it is inherently destructive: It does away with better products and the market for them and caters instead to consumers who didn’t need the product until they were constituted as a new market”

When technology industries disrupt, they often do so in ways that favor the privileged while disproportionately harming minorities. Disruption is seen as moving quickly, taking financial risks, and benefitting from introducing fluctuations into markets. This model for disruption can be summed up with Facebook’s original slogan “Move Fast and Break Things.”

But, as Worley points out, this is not the only model of disruption we have as writing and rhetoric scholars. There are methods of using disruption, not as violent interjections but as ways of shifting discourses. And, I believe that is what Hertz is getting at when he says that design can be “a way to punch Nazis, without the punching.” The zine disrupts academic discourse in design theory, pushes against conventions of academic publishing, and works to amplify the voices of a number of artists and activists. What I see as disruptive in Disobedient Electronics is not how it includes aggressive, in-you-face artistic creations; rather, it is disruptive because of the ways in which it was designed to advocate for renewed attention to social justice issues within design communities.

If we are to work toward a form of design advocacy—one in which we take seriously the call to action by Jialei Jiang and Jason Tham—then we ought to teach and practice design methods which “consider design as a social action for sponsoring ethical rhetorical practices, and accordingly, as an avenue for fueling social justice work.” As such, Hertz’s zine is a model that demonstrates a number of ways in which students can approach design advocacy and disrupt discourses surrounding systemic forms of oppression.

The disruptive approach I am suggesting is one that encourages students to actively expand and interrogate what material forms students use, the audiences they address, and the ways in which their arguments are framed. As I continue to work on these ideas in my own teaching, some questions I am dwelling on in relation to design, advocacy, and disruption are:

- How might we disrupt the emphasis in student writing away from proving or disproving particular arguments toward an emphasis on locating, curating, and synthesizing particular voices and perspectives? And, what would this look like in a multimodal writing classroom?

- How can we disrupt particular assumptions about writing conventions in our classrooms? And, how might we work to value unconventional compositions outside academia?

- How can we reframe the aim of design in our classrooms to privilege broader social justice concerns over persuasive marketability?

- And, borrowing from Hertz, how can we shift discussions of design in digital writing away from valorizing the latest trends or shiniest technologies towards active engagement with social justice issues?

Works Cited

Hertz, Garnet. Disobedient Electronics. 2017

Jiang, Jialei and Jason Tham. “Multimodal Design and Social Advocacy.” Digital Rhetoric Collaborative Blog Carnival. 2019.

Worley, Meg. “The Rhetoric of Disruption,” in Disrupting the Digital Humanities, 2017.