I think the best way I can show what digital rhetoric means to me is by showing how I have attempted to enact it.

Shortly after news broke about the suicide of Tyler Clementi, a young Rutgers student whose sexual liaison with another male student was video broadcast by his roommate, I wanted to compose a piece that would commemorate this young man while also drawing attention to the ongoing psychic trauma inflicted on young queer people growing up in a homophobic society. And yes, our society is homophobic, just as it’s also racist, sexist, ableist, and classist. If you haven’t yet accepted this reality, your head is still in the sand. And yes, I know, I know: gays can serve openly in the military. But isn’t it strange that they are securing this “right” at the federal level before marriage rights are offered? Gays can openly die for their country; they just can’t openly love in it. The message is clear: we’re ok with dead queers; we’re still unsure about living, breathing, loving queers.

And that’s the society that Tyler Clementi was growing up in. But he was also growing up in a society that has increasingly embraced its technological tools to enhance communication, to connect with one another, to build friendship networks, and to facilitate the sharing of information, ideas, and insights. We in composition studies have also increasingly embraced these tools, taking to heart the many ways in which they enhance students’ communicative abilities and expand our notion of what literacy and literate action mean. In our eager embrace, however, we sometimes forget that those tools of communicative possibility can also be tools of surveillance, of monitoring and disciplining interactions that individuals or larger groups find suspect. Tyler, unfortunately, discovered this lesson all too well, his private sexual embrace of another man caught on a webcam and discussed—and ridiculed—by others.

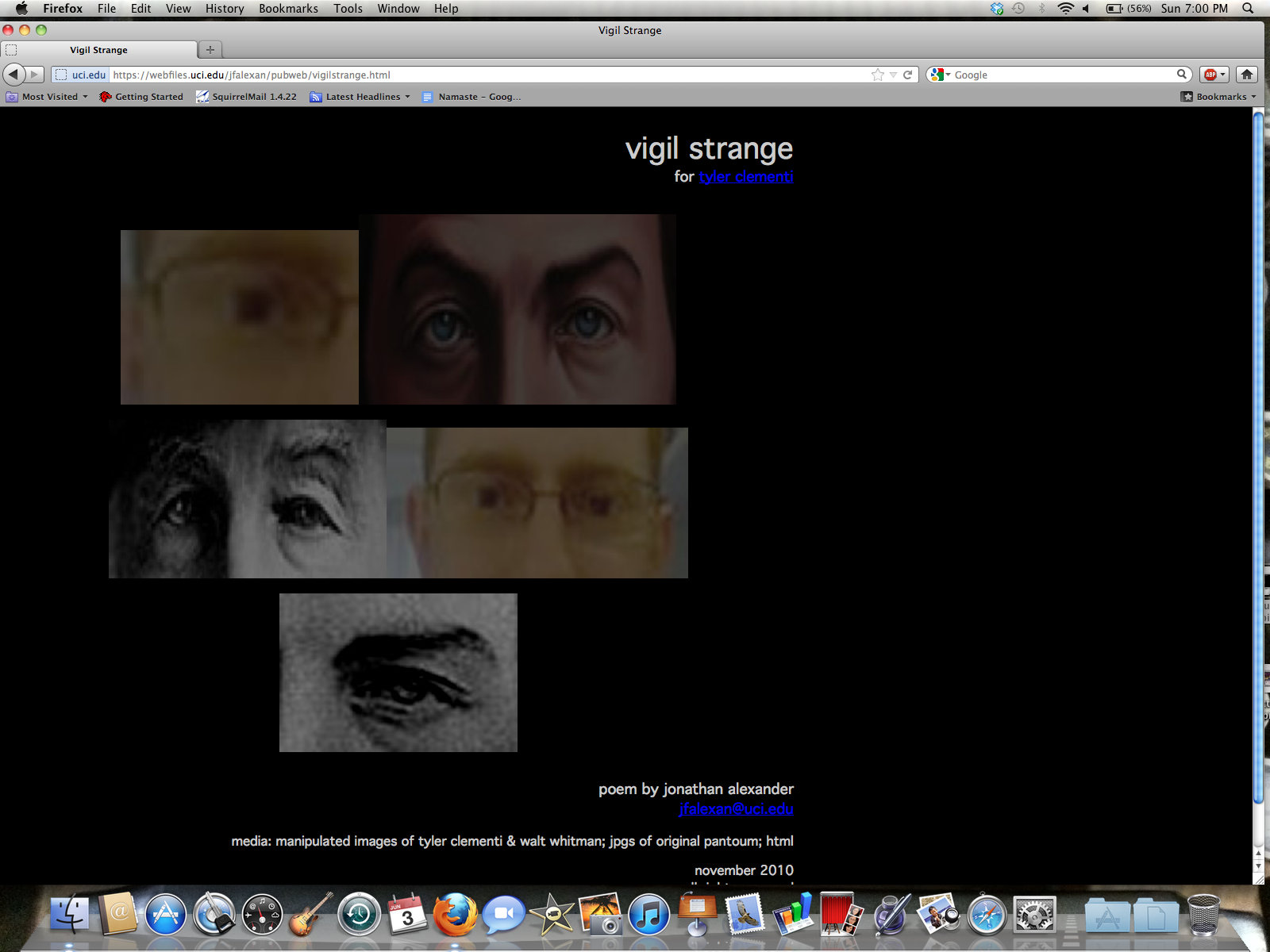

As I thought about what I would write in response to my own feelings about Tyler’s suicide, I kept coming back to the necessity of doing something online. I had started a poem, a pantoum actually, but realized soon that I wanted to create an interactive interface that might instill in readers a sense of the hauntedness that Tyler must have felt—the haunting specter of homophobic eyes prying into his life. I also wanted to connect his untimely death to a set of meditations on democracy and the promise of free association. Walt Whitman and his dedication to both democracy and the love of comrades seemed appropriate, particularly Whitman’s poems of the Civil War, in which he nursed many dying soldiers through a war that questioned to the core the very democracy he held so dear. So Whitman’s lines, the poet’s eyes, Tyler’s eyes, and lines from the roommate announcing Tyler’s sexual activities—all became mixed for me in an e-poem that I hoped would express poignant frustration at ongoing homophobic violence visited on young people: https://webfiles.uci.edu/jfalexan/pubweb/vigilstrange.html.

As I worked on this personal meditation, I began thinking of larger issues evoked for me—issues pertaining to the work that many of us have dedicated our lives. I quickly came to feel that Tyler’s unfortunate death brings together several issues that we in composition studies must face, particularly as we strive both to enhance the quality of our students’ literate participation in a pluralistic democracy and consider the increasing role of complex communication technologies in that participation. On one hand, we cannot ignore the many ways in which our students are practicing literacy and developing rhetorical skills through a variety of new media tools; new media offers us rich opportunities to think with our students about what literacy means in the 21st century as well as what kinds of rhetorical strategies they need to participate robustly in new digital public spheres. On the other hand, we need to be aware with our students of the ways in which such technologies can be used not only to monitor these public spheres but also to threaten or to silence voices. In some extreme cases, as we’ve recently seen in Egypt, entire networks used to mobilize protest have been shut down. In more subtle but still damaging ways closer to home, people’s communications are monitored in ways that limit their self and collective expression. Tyler’s roommate’s use of communication technologies is just one of many possible examples. Indeed, Tyler did not intend for his private sexual encounter to be made so public. The fact that it was, and the fact that he felt distressed enough about this revelation to commit suicide—both speak powerfully about interlocking systems of communication and surveillance that facilitate networks of homophobia. How can we challenge and resist such networks?

An unfortunate response to Tyler’s suicide would be further monitoring, more surveillance, particularly of students’ use of communications technologies. The goal shouldn’t be the limiting of access—but rather a newer and more complex understanding of how we use these technologies, what our relationship to them is, and how they become prosthetic extensions of ways of thinking. The organizers of the It Gets Better Project (http://www.itgetsbetter.org/) knew this quite well, as their response was not to argue for banning communication but enhancing it by creating hundreds and hundreds of videos of adult queers sending messages of support and encouragement to young people. The project’s aim is simple, its request heartbreakingly poignant: “Many LGBT youth can’t picture what their lives might be like as openly gay adults. They can’t imagine a future for themselves. So let’s show them what our lives are like, let’s show them what the future may hold in store for them. The goal here is to flood the network with positive messages, to use narratives of possibility to counteract the devastating effects of homophobic messages. The videos—now thousands of them—help young people develop a language with which to understand their lives as possible, as livable, as imaginable.”

This request for videos and messages of hope offers us a powerful way in which we can use our communication technologies—to imagine a future. I know this might strike some as naïve, but I increasingly believe that any hope we have for sustaining a pluralistic democracy will rest on our ability to imagine a future in which people’s choices for their lives are respected and honored across interlocking and shifting perceptions and understandings of race, sex, gender, ability, and intimacy. Further, I believe that much economic injustice is a direct result of a failure to respect individual and group choices for self-determination. In the process, we limit our imagination–individually and collectively–in envisioning a more just world. It Gets Better is in many ways both a promise and a hope that we will be able to continue to make good on that promise—that we can collectively work together to ensure for each other the best possible future. And indeed, some folks are putting such hope into practice. The necessary counterpart to It Gets Better is the Make It Better Project (http://www.makeitbetterproject.org/), which offers concrete advice to those seeking to improve the lives of LGBT youth.

For those of us in composition studies, It Gets Better and Make It Better should represent a powerful way in which issues of diversity and the possibilities of technology meet and embrace in hope for the future. Study it with your students. Investigate the rhetorical and material circumstances that have given rise to—indeed, that have necessitated—the development of such sites. Consider the circulation of messages across complex networks and their psychic and somatic impact on individuals and groups. And understand that we need both a better understanding of how to use these technologies and that we need a richer language to imagine diverse lives. Offering both to our students should be our highest priority, our greatest calling.