Review by Elizabeth Davis

Read more about session F12 on the C&W conference site.

Panelists

Carra Leah Hood, Richard Stockton College of New Jersey

Fred Johnson, Whitworth University

Jim Kalmbach, Illinois State University

Storify, printed texts, website templates. On the surface, three very different technologies and media of representation, but the unlikely juxtaposition of the three in this Saturday morning session of Computers and Writing 2013 resulted in a fruitful interrogation of the significance of the interface. Through their presentations, each of the panelists asked us to think about how form affects content and reminded us of the value of looking at the way the textual interface structures and influences the way we receive and interpret information. Though I was drawn to this session largely because of my interest in curation tools like Storify (highlighted in the title of Hood’s presentation), the whole panel served to deepen my conviction that we must continue to call attention to the way content is delivered.

Hood joined the panel virtually with a narrated slide presentation in which she provided some background on Storify, noting in particular the social media curation tool’s close association with journalism and events like the Egyptian revolution of 2011. She then moved to the main focus of her presentation, an account of how she used Storify to construct a multimedia presentation of her poem, “As the Crow Flies,” inspired by the death of her father. After reading the text of the poem, she walked us through the process of uploading the original poem and a brief written description of its context to the curation tool; the collection of multimedia elements like images, sounds, and links; and the fragmentation and rearrangement of all the elements into three separate versions. Her account highlighted the way invention and arrangement are integral to creation in Storify and the way the interface itself fosters a particular compositional practice. Hood then demonstrated the way the versions create different experiences of the poem, with multimedia elements like audio clips and fragmentation/rearrangement serving to emphasize literary devices like alliteration and enjambment. Such remediation naturally raises the question of which version of the text is “better,” but Hood’s answer to that was simple:

The remediation of the poem into a multimedia text and the use of Storify for a creative production (as opposed to a journalistic one) should cause us to ask not which is better, but what is important about such repurposing of tools and of texts, and Hood’s presentation effectively raised the issue of interface that became the focus as the panel continued.

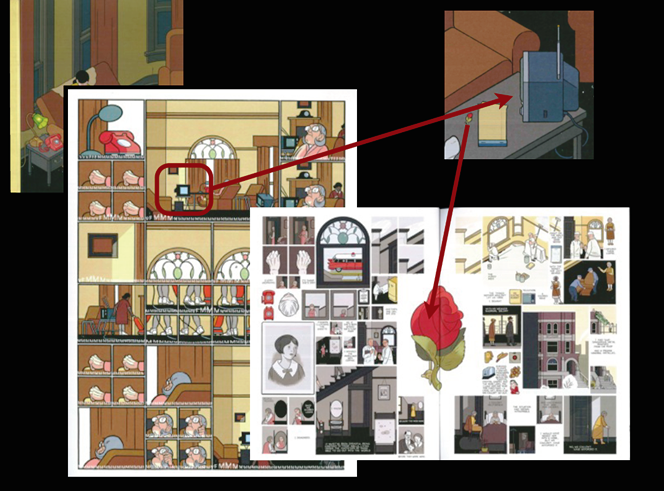

Johnson’s presentation focused on the artist and graphic novelist Chris Ware’s latest work, Building Stories. Even the title of the graphic novel prefigures its attention to the construction of narrative through the wide variety of textual interfaces that make up the “boxed set” that is Building Stories. Johnson’s goal with this distinctively undigital text was to put it in conversation with some key digital media theory, notably Collin Gifford Brooke’s argument in Lingua Fracta that we need to focus less on “textual objects” and more on “medial interfaces.” What does it mean to “read” an interface, which is really what we are being asked to do with Ware’s novel due to its complex presentation? One way, Johnson suggested, might be to consider it a hypertext, a claim he illustrated with an analysis of the way a particular image – a jeweled brooch in the shape of a rose – recurs in multiple places and how following the rose pin enables the reader to see similarities and patterns between elements of the text (even across different pieces of it) that we might not have noticed before.

In response to those media theorists like Lev Manovich and Jay Bolter who have claimed that such database-esque texts like hypertexts (or Building Stories) “free” us from narrative and the author(itarian)’s hand, Johnson cited Brooke’s argument that we should consider arrangement as a rhetorical practice of “patterning” that “invites interaction” in order to think about how authors can suggest pathways into narrative and meaning without forcing readers into a single experience of a text (think here, Johnson suggested, of Citizen Kane and the films of Sergio Leone).

Kalmbach’s discussion of organizational website templates and the “tragedy” (a term Kalmbach admitted was meant to be a provocation and not truly an indictment) of template rot, was nicely set up by Hood and Johnson’s attention to how interface structures both the composition and experience of a text. He started with the premise that templates have become the way we compose web documents of all types, including informational sites for companies, institutions and organizations.

Such websites are often complex structures in which pages and subsites exist in an information ecology where design plays a key role in establishing a coherent identity or message. So what happens when a template misaligns due to changes in the ecosystem’s design or architecture? Kalmbach identified three general strategies that site custodians resort to in the face of template rot: 1) Duct Taping, 2) Appropriation, and 3) Myspacing, each of which he illustrated with some well-chosen examples. While Duct Taping and Appropriation are mindful in their re-purposing of widgets or template elements, Myspacing, in which information is inserted willy-nilly into “cracks” in the template, seemed most interesting from a rhetorical standpoint to Kalmbach, and he noted that he intends to theorize that strategy further. Kalmbach’s main premise in the presentation emerged from the idea that we have to recognize the opportunities that arise out of template rot as a way to teach students how to best evaluate and, ultimately, use templates effectively in site design. Such a pedagogy must foster a through/at approach that asks students to consider not only the content of a site, but the interface itself in order to see the possibilities for rhetorically mindful action.

In thinking about the way connections and, if I may borrow the term from Johnson’s presentation, patterns, emerged from this panel, the idea of the interface again looms large. The mediating interface of the conference panel placed these presentations in conversation with each other in such a way that productive discussion about the composition of texts – whether creative or technical, digital or print – emerged during the Q&A, and, for this attendee, sparked a number of questions. How does spatiality affect the construction (literally and figuratively) of meaning? What design and rhetorical concepts are most vital to an interface-conscious composition pedagogical practice? Where is systems/network theory in all this? I expect to be happily grappling with the questions provoked by this panel for months to come.

Elizabeth Davis is the Coordinator of the Writing Certificate Program at the University of Georgia. She teaches writing courses in the Department of English and her current research foci are e-portfolios and curation as a digital media compositional process.