Thanks to freeware toolkits like AntConc, and searchable databases like the Corpus of Contemporary American English, or COCA, it is easier than ever to analyze electronically-available texts for linguistic patterns. This practice is called corpus linguistic analysis, and it transforms written language into word frequencies and patterns largely impossible to note in conventional reading. It therefore enables us and our students to be analysts of written language in new ways–even to analyze texts that have never been examined as such.

I use corpus linguistics in my work because I am interested in the tacit patterns that characterize academic genres (and thus the values and expectations therein), and so you will see that my recommendations below are related to both teaching and research. My primary research, which informs my teaching of writing, is rhetorical and corpus linguistic analysis of academic discourse, particularly what characterizes the writing of students new to higher education. Because academic writing can be a dense and high-stakes form of discourse, one of the many things I like about corpus linguistic analysis is the way it can demystify patterns in advanced academic writing and also clarify how students’ writing is sometimes different.

What exactly is it? In short, corpus linguistic analysis is the computer-aided analysis of linguistic patterns in and across naturally-produced texts. The object of study is called a corpus (multiple: corpora), which is a searchable body of naturally-produced texts for patterns like the following:

- Salient word frequencies (think word cloud)

- Concordance (words in textual context)

- Concordance plot (distribution of words in and across texts)

- Keyword analysis (salient words compared to other corpora)

- Collocations (words that co-occur; lexical company words keep)

- Clusters (clusters of words that appear frequently; e.g., it is * to note, or I will * *; see below)

- Lexical trends (frequency and distribution of particular words or kinds of words; e.g., those that understate or overstate, such as likely, somewhat, certainly)

- Lexico-grammatical trends (colligation: grammatical company words or phrases keep; e.g., negative, possessive, or modal—ex: the verb budge tends to be negative)

The emphasis on naturally-produced texts means that corpus linguistic analysis emphasizes studying language in use, rather than making claims about language and texts based on decontextualized (or few) examples, speculation, or prescriptive rules, and so the approach has much to offer the research and teaching of language.

What many researchers and students don’t know is that basic corpus linguistic analysis can be easy and fruitful.

Here are some basic steps, followed by an example use:

(1A) Identify linguistic features that you are interested in exploring further in a body of texts to which you have electronic access. Consider 2-3 linguistic patterns which interest you in texts you regularly examine, such as in student essays in a course you teach. In the case of teaching, these might be 2-3 linguistic features to which you think students could pay more attention.

(1B) OR Identify texts you want to examine without knowing what linguistic features you are interested in exploring. If you do not know what features you want to explore upfront, you can alternatively begin with step (2) and then run a word frequency or cluster list on AntConc to see what kind of patterns emerge.

(2) Create a corpus. You will want to create a corpus of the texts (e.g., of the student essays) by saving each Word doc as a .txt file (under “Save as”).

(3) Explore. Use AntConc to look (and/or have students look) for examples of the 2-3 linguistic features you have identified, and consider what patterns emerge.

(4) Compare. To see what might be particular to your corpus or not, you can compare the same patterns in COCA in or across registers (including the academic register, comprised of published research articles, as well as fiction, newspaper, magazine, and spoken).

AntConc and COCA are both user-friendly, but one good place to start with AntConc is the “Read me” file on the website above, and/or the article by Ute Römer and Stefanie Wulff called “Applying corpus methods to written academic texts: Explorations of MICUSP” (Journal of writing research 2.2 (2010): 99-127). This article has the added bonus of introducing readers to another valuable corpus, the Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Papers, or MICUSP, which consists of over 800, A-graded papers across 16 disciplines and 4 student levels (final year undergraduate through 3 years of graduate school). Likewise, COCA contains information and examples on its main interface.

Example: “Don’t use I” Using I in rhetorically appropriate ways identified via corpus linguistic analysis

We all know that the rule “don’t use I” that students often hear in high school is prescriptive and simplistic. But students sometimes move from “don’t use I” in high school to “use I sparingly” or “use I when it serves your purpose” in college, and these iterations may not be much more clear. After my own explorations of “I” in students’ writing and in published academic writing, I saw a key distinction between the two which was captured in formulations that began with “I will.”

I wanted my students to witness these patterns and interpret them for themselves, so I invited first-year students to analyze the use of “I will” in their own papers compared to the same in the COCA academic subcorpus. We started with 4-word phrases beginning with “I will.”

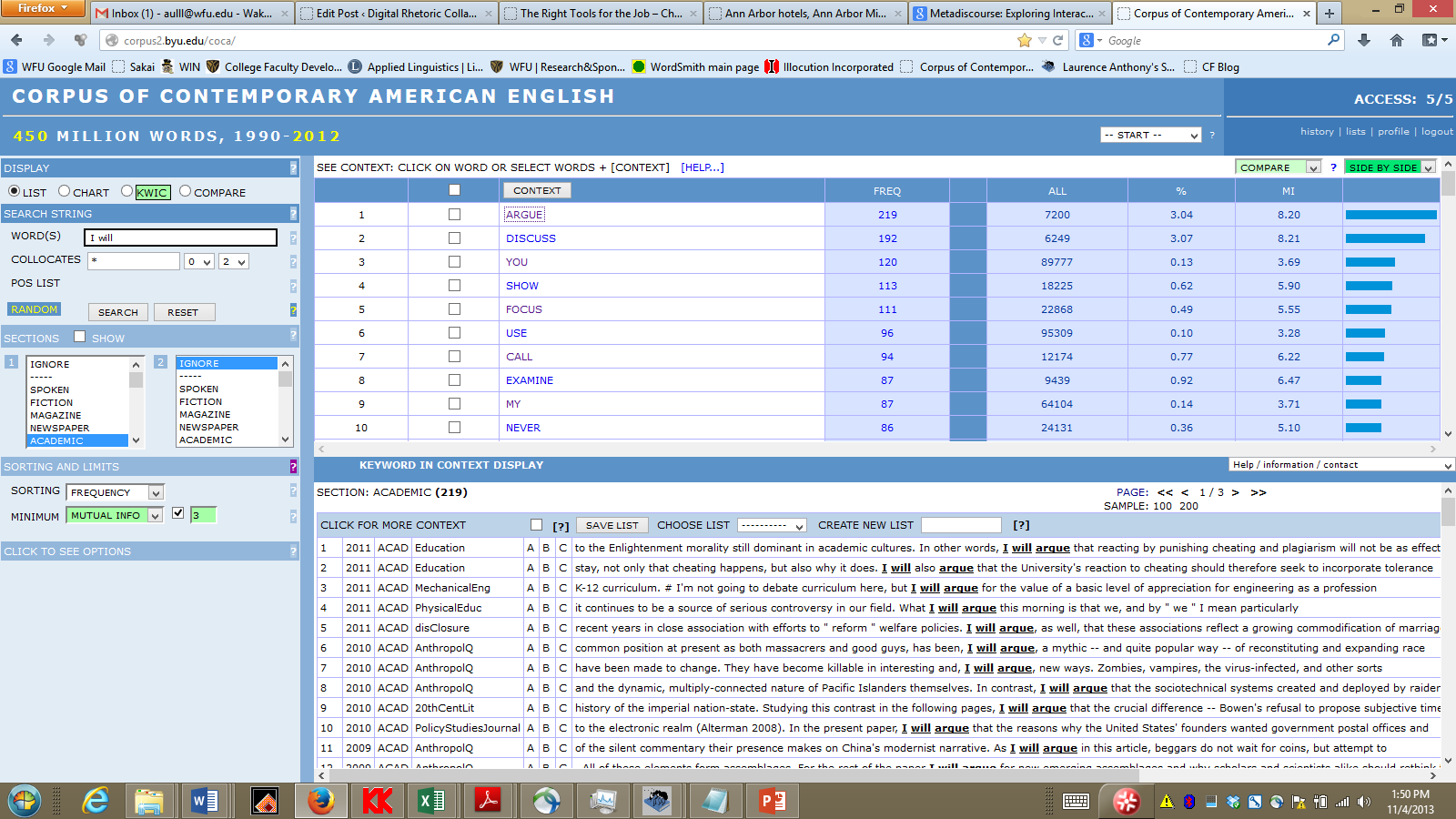

First, using the COCA academic subcorpus, the students looked for words one and two to the right of “I will” using the “collocates” tool (see left panel in screen shot below, which restricts COCA to academic texts only). Reading the collocates and the examples in use (which appear below the list when one clicks on any given collocation), they found that advanced academic writers use “I will” formulations as a way to create a logical sequence for their readers (e.g., I will focus on) or to stake a claim (I will argue that).

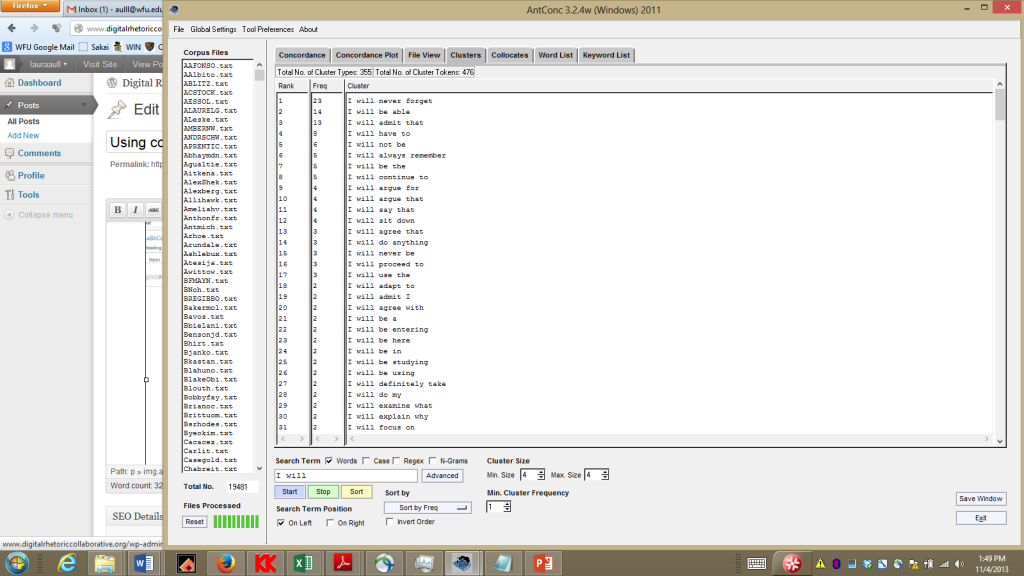

The students then used AntConc to look at their own writing and, using the “clusters” tool, looked for four-word clusters beginning with “I will.” They found that in contrast, they most often used “I will” in narrative and subjective forms–e.g., I will never forget, or I will admit that–rather than in the ways that more advanced academic writers used “I will” to carve out space for an argument or to lead a reader through it.

After the students observed these patterns in their own and in published academic texts, they began to pay more attention to how they could use “I” to their advantage in academic discourse. They likewise had a place to go for example uses. It didn’t mean that students could or did adopt examples they saw without question, but it did mean that they had patterns and examples with which to make informed decisions about their own reading and writing of texts. One of my students, now a third-year student at Wake Forest University, said it this way: “It is cool to think about writing by looking at tons of words instead of rules.”

1 Comment

This is fascinating! I was just talking about this shift in attitudes towards use of “I” in undergrad academic writing at a staff meeting, and wondering how better to communicate to my students about its nature as a rhetorically sensitive choice rather than a rule. This kind of analysis seems really well suited to having them arrive at that kind of realization on their own – and is something I did not know was possible, let alone in a manner easily accessible to FY students. Thanks so much for sharing this!