by Benjamin Miller, Amanda Licastro, and Jill Belli

![]() We are the principal designers of the Writing Studies Tree (WST), a project we hope you’ve heard about since our launch at the 2012 CCCC in St. Louis. Briefly, the WST is an open-access site for gathering, visualizing, and analyzing “academic genealogies”: the often-invisible systems of affiliation and influence formed as individuals write dissertations, train as teachers, and study and research together throughout their careers. We had seen many of these “family” reunions at conferences, at which junior and senior faculty from across the globe turn into grinning alumni of (e.g.) Purdue or CUNY or Ohio State and take over publishers’ parties and hotel bars — but there was no place to track who had worked where with whom, so a lot of interesting connections were remaining unmade. How many panels or coauthored papers came together because their authors studied together, or (even harder to detect) because their faculty advisors studied together, years before? Individuals may have anecdotal knowledge of such things, but if left disaggregated from other comparable histories, they could be lost entirely. The Writing Studies Tree allows us to crowdsource and combine this information into a rich set of “boutique data” for ongoing exploration.

We are the principal designers of the Writing Studies Tree (WST), a project we hope you’ve heard about since our launch at the 2012 CCCC in St. Louis. Briefly, the WST is an open-access site for gathering, visualizing, and analyzing “academic genealogies”: the often-invisible systems of affiliation and influence formed as individuals write dissertations, train as teachers, and study and research together throughout their careers. We had seen many of these “family” reunions at conferences, at which junior and senior faculty from across the globe turn into grinning alumni of (e.g.) Purdue or CUNY or Ohio State and take over publishers’ parties and hotel bars — but there was no place to track who had worked where with whom, so a lot of interesting connections were remaining unmade. How many panels or coauthored papers came together because their authors studied together, or (even harder to detect) because their faculty advisors studied together, years before? Individuals may have anecdotal knowledge of such things, but if left disaggregated from other comparable histories, they could be lost entirely. The Writing Studies Tree allows us to crowdsource and combine this information into a rich set of “boutique data” for ongoing exploration.

Our Goals

When we set out to record, organize, and visualize the history of mentorship and collaboration in writing studies scholarship, we were both inspired and limited by the existing projects in other disciplines, including the Mathematics Genealogy Project, Phylo, and the AcademicTree network (NeuroTree, FlyTree, PsychTree, etc). While these sites worked to provide browseable data, the relationships they focused on left out many of the lines of influence in our field — not just dissertation advising, but also training by writing program and writing center directors, influential coursework or writing project participation, and more. And, as compositionists, we also wanted more than data: we wanted to promote meta-awareness and network sense. The Writing Studies Tree had to involve its users as active creators in a shared knowledge-making project across generations.

Given the data we were trying to compile, here’s what we knew we wanted from the platform:

- It had to be openly editable by large numbers of users. Not only did we want users to edit and curate the network collectively, for that active meta-awareness, but we also wanted to scale up rapidly from small acts of participation to useful amounts of information.

- It had to capture different kinds of connections simultaneously, e.g. among people and between people and institutions. Importantly, these connections had to be both reciprocal — the platform should be able to automatically link person B to person A when A is linked to B — and directed, i.e. we should know whether person A is the “ancestor” (mentor) or the “descendant” (mentee).

- It had to be able to interface with visualization tools, allowing us to consolidate large quantities of data through a visual graph, map, or tree.

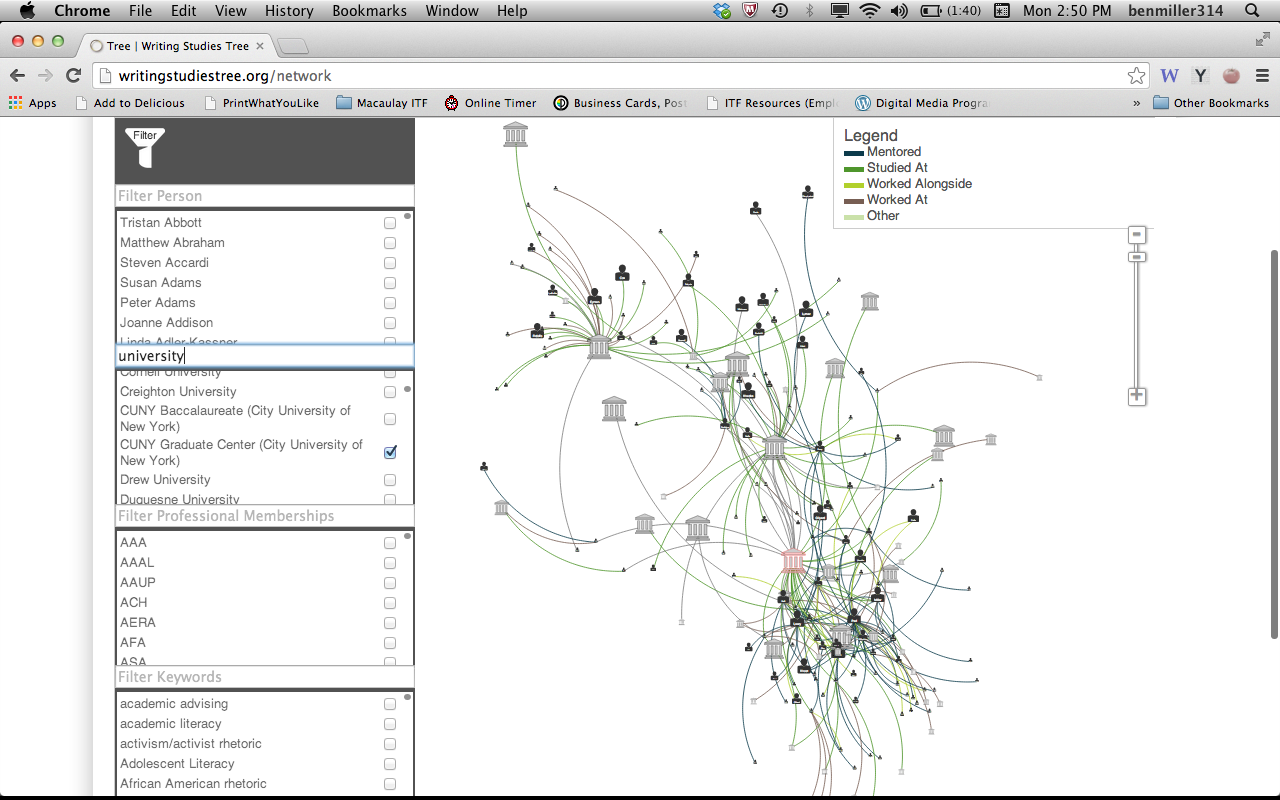

- Ideally, we wanted also to record and filter by specific types of relationships and timeframes, so that further analyses and visualizations could be conducted later on.

- Because of the crowdsourced nature of data-gathering, we had to minimize user error and vandalism; therefore, the platform needed to store revision history, and we decided to limit the data gathered to verifiable facts.

- Existing entries had to be searchable, ideally with auto-complete and default wildcard matching.

- Finally, both the backend and the frontend had to be manageable by the “non-techies” among us.

A Learning Process

According to those we consulted — including Chris Alen Sula, co-creator of Phylo, and Boone Gorges, lead developer for the CUNY Academic Commons — the natural choice of platform was Drupal, because it could take care of needs 1 and 2 out of the box, with modules for many others. However, we resisted that solution because of Drupal’s reputation for a steep learning curve (see need 7), frequent schedule of required updates, and policy of ignoring back-compatibility when updating. So we built and tested a slough of alternatives: A simple Google spreadsheet. Wikidot. XML. A wordpress.com site. A wordpress.org site with the Pods framework plugin. Omeka. DrupalGardens. Google spreadsheet Forms. Forms embedded in WordPress. All of them failed on one criterion or another, and most failed in more than one way.

So, in the spirit of failing forward, we gave Drupal a try… and it stuck. Learning Drupal was by no means challenge-free — we collectively watched some 200+ videos in the NodeOne Learning Library, narrated by the fabulous Johan Falk — but the advantages were clear, in large part because we now knew that Drupal was the best option for our needs. We’d already tried the others.

In particular, Drupal is designed around a node-based architecture, and assumes you’ll want to customize fields on those nodes. This means we can simultaneously provide open text fields for stories and anecdotes, and pair them with structured data (names, dates, relation types and subtypes) that make those stories more discoverable. A vast library of free modules such as Relation Add help guide users through the process of linking these nodes to each other. And, because Drupal is open source, we can modify these modules or contribute new ones to suit our needs.

Product and Prospects

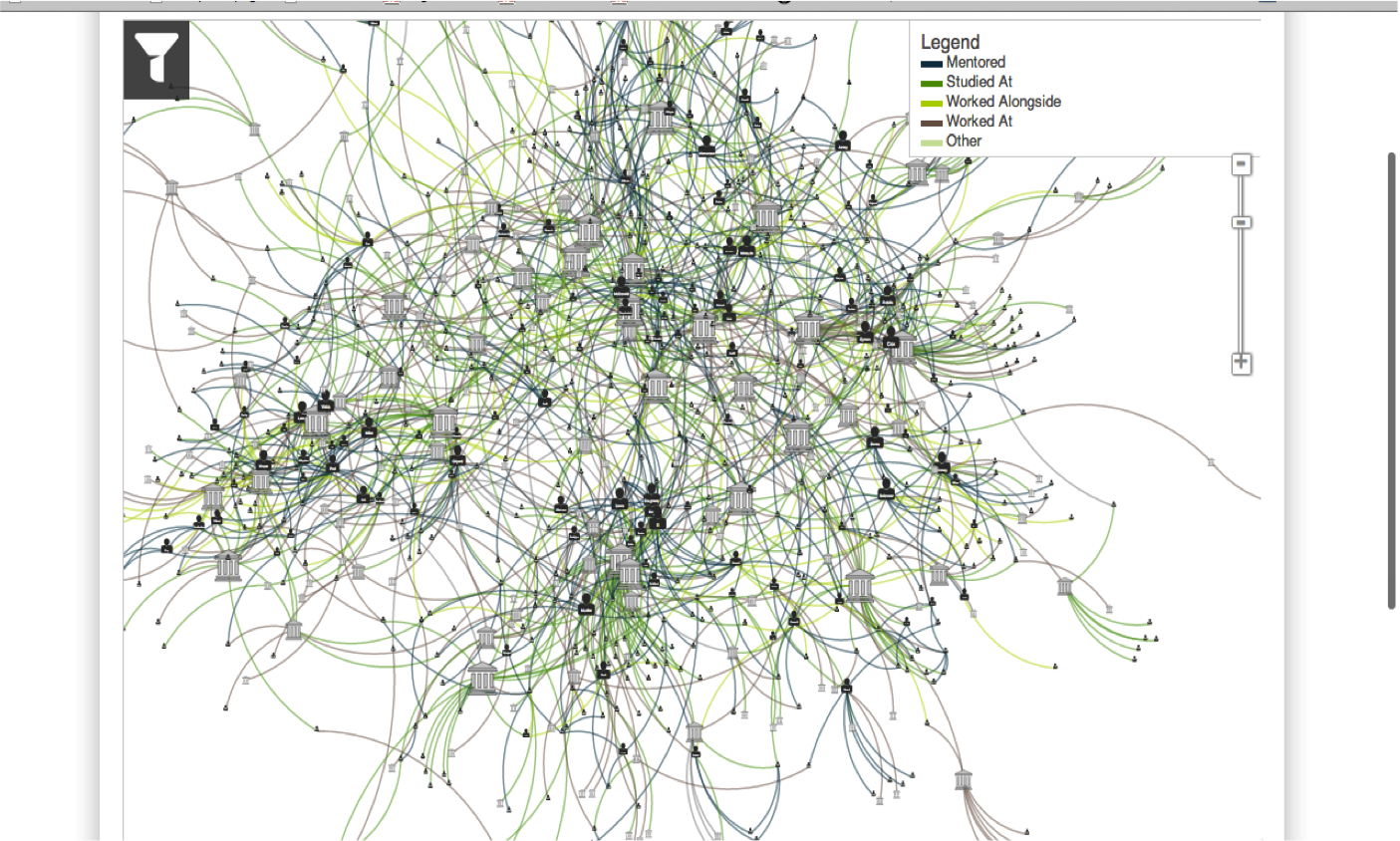

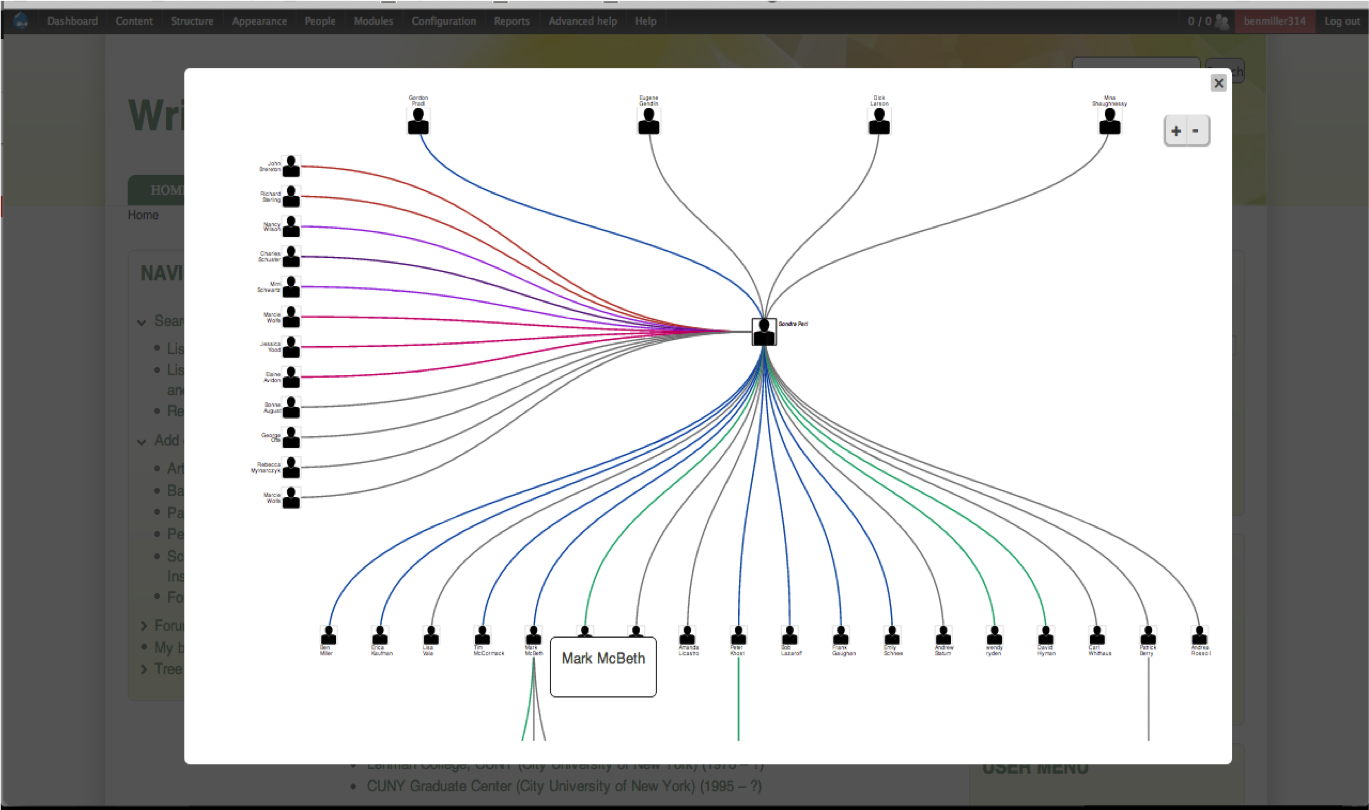

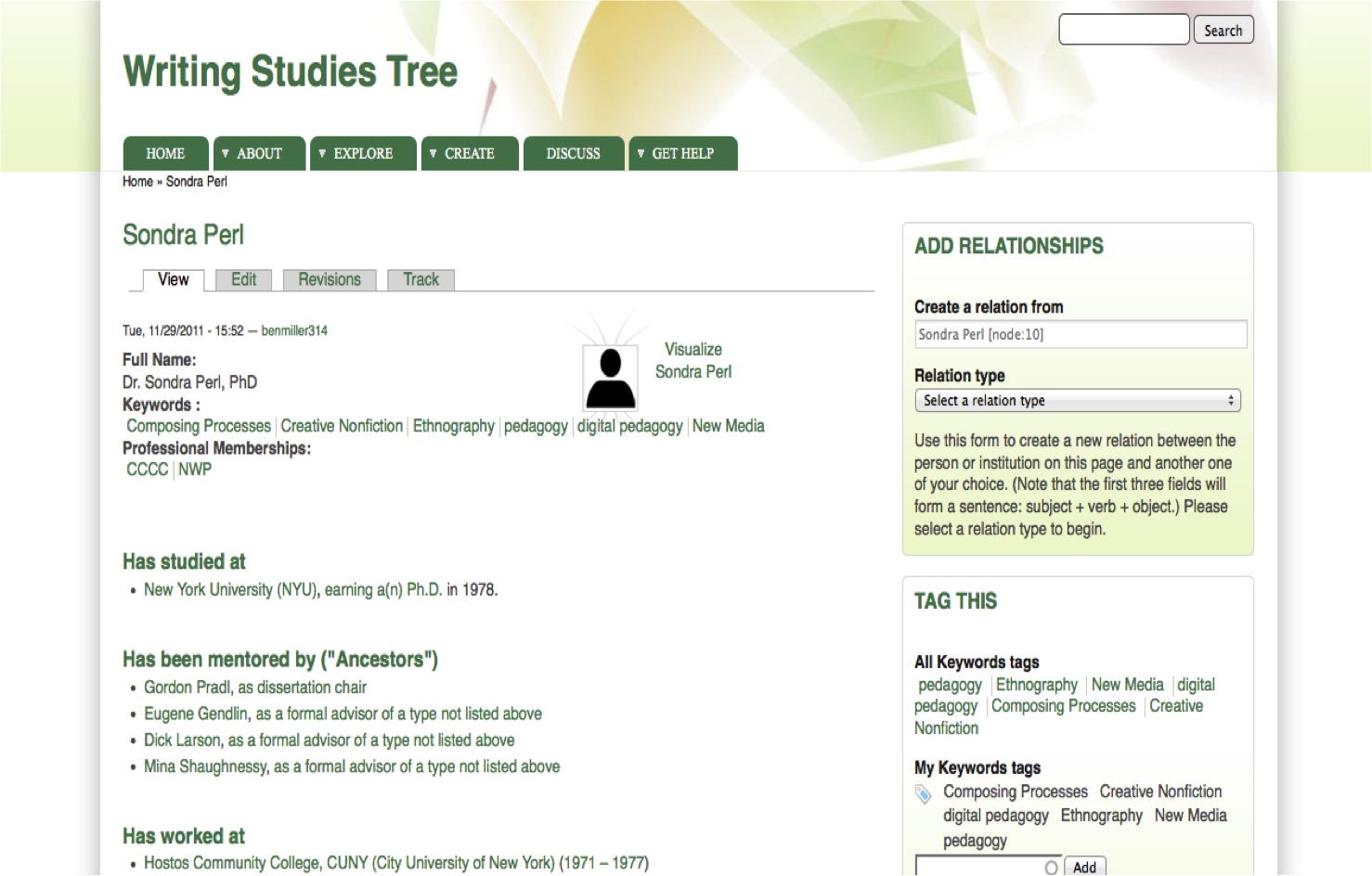

To date, the Writing Studies Tree incorporates many of our original goals: users can add people and places, and connect them via an array of relationship types. You can explore the data in at least three interlinked ways, including a family tree view, a profile view with “siblings,” and a force-directed graph of the full network of people and institutions.

With support from our project advisers Matthew K. Gold and Sondra Perl, we were awarded funding from two Provost’s Digital Innovation Grants (2012, 2013) at the Graduate Center, CUNY. These funds enabled us to contract programmers Matt Miller and Jeffrey Binder to implement some filtering features that help enhance the readability of the visualizations, as well as to hire Jamie Kutner to design our branding materials.

And as we like to say, the Writing Studies Tree is in perpetual beta. Between the requests we receive on our user forums and at our conference presentations — and our own scope creep — the possibilities for growth seem boundless. Our work is ongoing, including an effort to enhance the usability of the site, refine our visual impressions of the major clusters emerging in the full network view, and add additional visualizations such as a timeline or map view. We are actively in search of collaborators who can work with us to overhaul the site’s appearance and interaction architecture, which have been in place since our first forays into Drupal.

Most importantly, we need participation. This tool relies on the knowledge of users to grow, and feedback from the field to thrive. Visit the site or come see us at MLA in Chicago and CCCC in Indianapolis. We welcome questions, suggestions, and collaborators of all kinds as we continue to build a tool that is useful and usable for our community!

1 Comment

Thanks for sharing this wonderful and important work, Ben, Amanda, and Jill. The way you describe the trials and errors behind pairing the WST’s project goals with an appropriate platform is really useful for anyone in the early stages of crafting a digital environment. It had been such a pleasure to contribute to this project and to watch it evolve!