The photo above exemplifies how bilinguals communicate with hybrid sense-making strategies. I collected the image during my fieldwork at an after-school program in Kentucky–data from a larger ethnographic project exploring literacy practices in Latino barrios in New York City and Kentucky. As one can gather from the afternoon’s activities, the celebration of books was a social event for families, and one celebrated bilingually. Over 100 families from the community were in attendance, which was not an unusual number for this particular after-school program. Most of the adults in attendance were monolingual Spanish or English speakers. The majority of elementary and high school students, however, were bilingual, and the program conducted all events in Spanish first and English second.

Bilingual singing and play at an after-school program celebration for the end of the school year. The two singers considered themselves emergent bilinguals learning Spanish.

I have been researching bilingual after-school programs for nearly a decade. I’ve interacted with emergent bilingual youths, college students, and adults with expansive languaging repertoires. I use the term translanguaging as figured in activity rather than the nominative translingual, but I press this active definition further by de-linking monolingualized assumptions of bilingual practices by opting for translanguaging. Translanguaging refers to bilingualism movements as dynamic communicative actions. Rather than ignore emergent bilingualism or perceive it as a problem (García), translanguaging recognizes that emergent bilinguals extend their translanguaging repertoires as they develop stocks of practical bilingual experiences from which to strategically respond to daily activities (García, Flores, & Woodley).

- Comic strip by ten-year-old mentee in New York City. The stories in her collection recount events in her neighborhood. In this scene, she describes a violent encounter with a bully.

Translanguaging is a bilingual theory for social justice that challenges monolingual assumptions permeating current language education policy and monolingual ideologies. The unfortunate tendency in individualist social orders such as in the United States and global north is to internalize standardized measures as social aspirations, and thereby internalizing constraints standing in the way of standards as personal failure, even guilt, for speaking another language besides English. It is important for educators to critically question our “self-actualizing,” individualist impulses for standardization that structure certain legitimate forms of bilingualism from those considered illegitimate in the acquisition of measurable skills and knowledge (Horner, Lu, Royster, and Trimbur). The Translingual Writing website offers an exceptional database of current multidisciplinary research for the growing field of research.

Mentorship from teachers and communities has the potential to correct these individualized-monolingualized views by scaffolding collective learning. Targeting misinterpreted “deficit” views of language-minoritized students reorients views of English language learning to that of emergent bilingualism, or to a translingual orientation that applauds the innovative and creative abilities to shuttle across diverse language resources. Innovation and creativity are both essential to teaching and learning English, and if put in alignment with a pedagogy grounded in confianza, a translingual approach honors the literacy practices of local communities (Canagarajah).

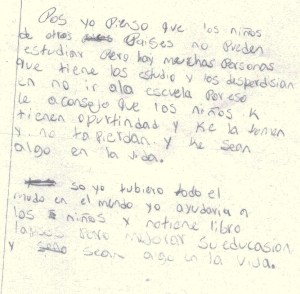

- A response to a photograph in a Spanish language newspaper composed by a fourteen-year-old mentee at an after-school program in New York City. The Spanish and translated English read: “Pos yo pienso que los niños de otros paises no pueden estudiar pero hay muchas personas que tiene los estudio y los desperdisian en no ir a la escuela. Pos eso le aconsejo que los niños k tienen oportindad y ke la tener y no lo pierdan y ke sean algo en la vida. Si yo tubiero todo el mudo en el mundo yo ayudaria a los niños no tiene libro lapices para mejorar su educasion y sean algo en la vida.” “Well I think that children in other countries aren’t able to study, but they are many people who want to study but who are lost because they can’t go to school. For this, I advise youth who have the opportunity to take it and not waste it so they can be something in life. I would give everything in the world to help the children without books and paper to improve their education and be something in life.”

Translanguaging Homework: Orientation in Practice

The NCTE Position Paper on the Role of English Teachers in Educating English Language Learners invites mainstream language arts and writing teachers to develop engaging curricula for emergent bilingual students that develop critical academic skills with relevance to students’ identities and communities. As the position paper rightfully highlights, teachers can help students develop English as well as support their bilingualism with sensitivity to their language and literacy needs, and those of their communities. The brief emphasizes that teachers’ sensitivities to the language and literacy needs of their emergent bilingual students necessitates learning about students and establishing connections of trust between students, families, communities, and schools. The position paper recognizes that relationships between teachers and emergent bilingual students must include knowledge of students’ families and communities. In the 2009 Standards for the Assessment of Reading and Writing, NCTE also takes the position that “families must be involved as active, essential participants in the assessment process” (Standard 11). This is the challenge teachers must face in involving the families of our students: to learn how to value the strengths of our students’ communities by gaining experience with our students’ communities.

Demystifying school policies, procedures, and assessments—such as standardized tests and college readiness indicators—increases school involvement and improves communication among language-minoritized communities and schools at all levels. In the example of the spelling test above, a mother asked me for suggestions and advice about how she could help her son better his spelling scores. The “self-actualization” for her in this case was admitting responsibility for her son’s failure, taking a sense of guilt because of her language-minoritized status. Together, mother, son, and I devised a system of notecard quizzes to practice with at the beginning of each week when the teacher distributed spelling words tested later each week. Though a small gesture, such translingual mentoring between schools, universities, and communities of families can foster further dialogue around assessment issues, trusting relationships on a common ground that disrupt meritocratic definitions of success or failure. With confianza, or the development of sustained trust, members of the school community can conduct honest and important dialogue about assessment. Families and educators collaborating can share their important perspectives on local and national conversations about homework, testing, literacy, and language learning. After-school programs with the expertise of K-12 and university educators will be able to look carefully and strategically at school assessments while also preparing and mentoring families for academic success. With the confianza of mentors, parents alienated by their children’s schools and the English language could directly come into contact with the language without institutional scrutiny.

Translanguaging Community Research

Ethnography by its social nature is a project in the genre of “Life Writing” which teaches its practitioners that we study something because we already know something. It teaches us about what we need to know in order to know more, and that we actively participate in our learning as we collect, sort, and theorize about data and artifacts. The substances of the ethnographic interrogation are the lives, or bios, that make social life. Composing ethnographic research as a localized discourse frames, categorizes, interprets, and critiques social life, but also its own discourse and the position of its researcher’s life. The researcher’s position becomes something like a broker between untheorized practice and practical theory, producing new knowledge from raw data collected in the field.

I have chosen to use an ethnographic methodology that gives precedence to the immediate experience of first-generation immigrant families. The activities and logics of agents in this study, myself included, should be understood as rational responses to structures into which we found ourselves historically embedded. Social interactions were the substance of our activities in the bilingual after-school programs fostered. The mutual acquaintance of individuals of different ages likewise represented an inter-generational chain of shared mutual knowledge, language differences, and how these shaped communicative practices between links. Years of data collected from diverse fields have shaped my community literacy research but also how I understand myself as researcher and emergent bilingual.

Interview with an after-school mentor in New York City about the educational devotion of families despite the program’s low budget.

In the interview with the mentor above, I was curious about his thoughts concerning the temperature issues facing the after-school program as the New York winter loomed. His answer moved away from what I expected in terms of fundraising and into how the cold would not deter families, as it hadn’t in the past. My expectations as a researcher have consistently been wrong when conducting fieldwork, especially as my perspective consistently changes as I participate with communities. The first fact one comprehends when conducting ethnographic research is awareness that careful observation can reveal only a slice of social life. As an anthropological method of research, ethnography provides a detailed, in-depth description of a corner of everyday life and practice within various configurations of social relations. The critical aspect situates inquiries within broader projects of social analysis within theories of narratives, languages, citizenship, education, and inequality.

Collecting data from students and analyzing for civic participation builds discussions about community cohesion and social ties that intersect with shared educational interests. Student-teachers conducting ethnographic research of emergent bilingualism analyze community fieldwork, from which students individually or in groups derive themes and words of special consequences. Contact zones are spaces for coding data collected in students’ fieldwork. Analyzing linguistic exchanges in contact zones recognizes moments of collision in diversity. For students negotiating language and identity, it is pivotal to understand their selves as students and members of communities. Such is the case in the following interview with eleven-year-old Luis in New York City. At 1:20 he language brokers between his mother and me about his visions for himself in the future.

Interview with a fourth grade homework mentee in New York City about what he knew of his mother’s schooling in Mexico.

Writing teachers likewise can gain from organizing community learning fieldwork projects for assignments for students, such as this community profile of local libraries submitted by a group of four first-year students enrolled in a Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Studies course at the University of Kentucky. Ethnographic projects with bilinguals in the community and programs that offer multilingual services can be a space for student researchers learning about and archiving local literacy practices. Writing teachers and students gain from learning about how local literacies function in day-to-day practice in their communities and homes with research involving families, neighbors, and additional members of students’ social networks develop ethnographic reporting procedures essential for academic research writing.

Ethnographic research can also take on different genres. The clip from the documentary film below comes from another community engagement ethnographic project. The short documentary explored an after-school program in New York City from the perspectives of parents, mentors, and scholars studying immigrant academic achievement and challenges.

Hunter College M.F.A. thesis documentary project by Christina Hernandez. The documentary helped a New York City after- school program to secure donations from different organizations.

Building on the strengths of communities means finding links between the profound resources for universities involved in community outreach, multilingual teacher training, and student mentorship programs for future teachers. Teachers at all levels must analyze and engage students’ funds of knowledge (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & González), or the bodies of their everyday knowledge learned through participation in home and community practices. One of Paulo Freire’s first tenets for literacy learning was for educators to prepare themselves for critical teaching in a community by first researching the language and conditions of students from which the lessons and themes of the syllabus will be generated. An extension of this, I propose, is also a personal connection with the communities one teaches, or a two-way sense of confianza.

3 Comments

Pingback: A Community Literacy Narrative for National Poetry Month - Literacy & NCTE

Pingback: Community Literacies en Confianza, Part I - Literacy & NCTE

Pingback: Community Literacies en Confianza, Part II - Literacy & NCTE