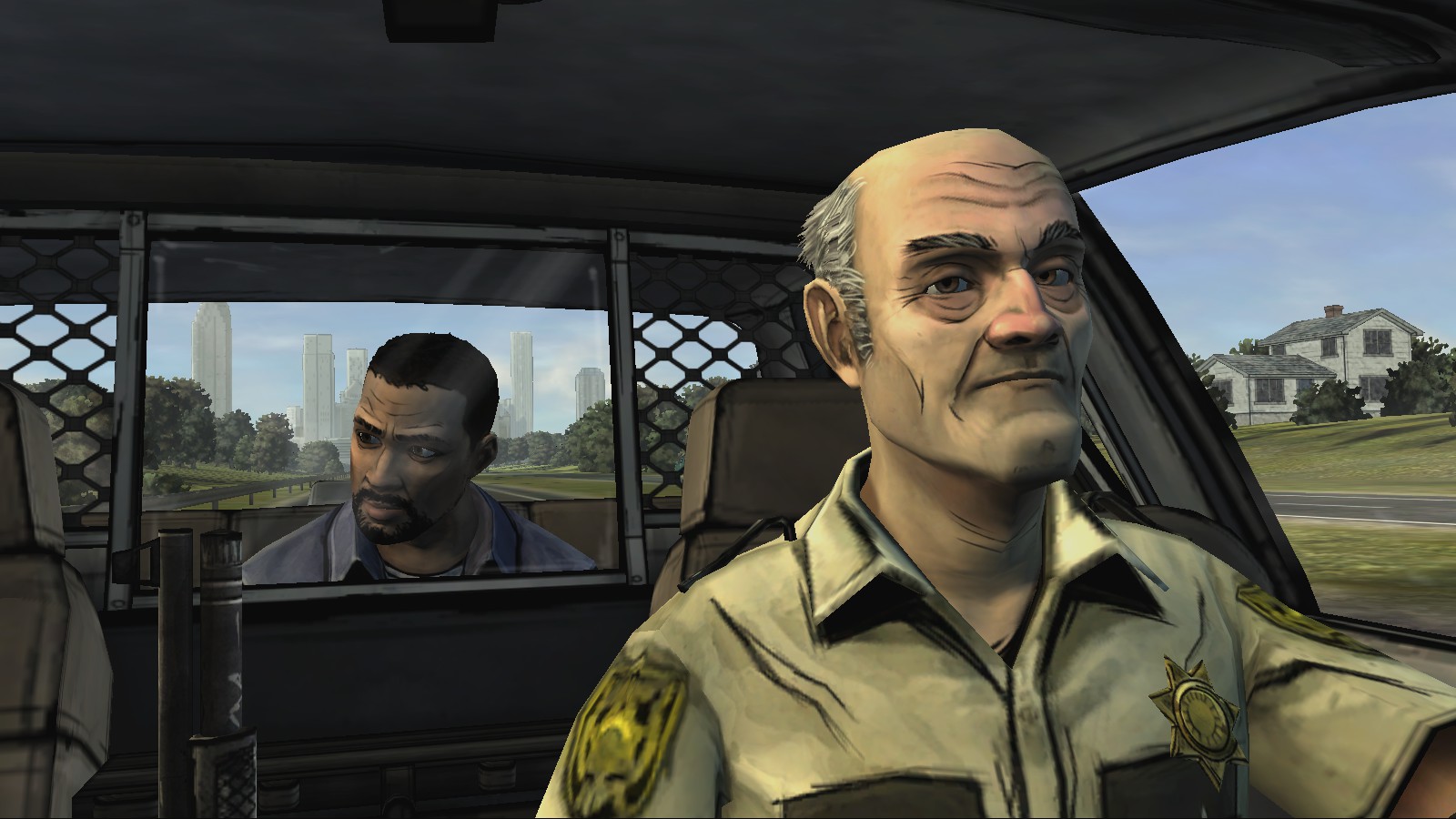

In 2012, Telltale Games released The Walking Dead, an episodic adventure game, to critical and commercial success. The winner of several Game of the Year Awards and many other accolades, The Walking Dead also is one of the best examples of a game that complicates the standard representation of black male characters in gaming and provides an opportunity for players to understand and craft racial identity. From the beginning of the game and throughout, players encounter a drastically different set of opportunities to experience and define race than those seen in games criticized for their representations of black male characters like Madden, NFL Street, or Grand Theft Auto. Some critics, like David J. Leonard, identify these games as “high-tech blackface” and note that “eight out of every ten black video game characters are sports competitors; black males, thus, only find visibility in sports games” (“High-Tech Blackface” 1). Thus, in these contexts, black male characters in videogames are typically rendered violent and aggressive due to the roles they are cast in without providing the player any choice or agency in these acts— they simply consume violent black masculinity. The Walking Dead, meanwhile, by virtue of being an adventure game with the mechanic of player choice at the forefront, allows players to participate in the construction of black masculinity instead of simply consuming it. Players do this by taking on the role of Lee Everett, a black male who opens the game on his way to prison outside of Atlanta, Georgia for committing murder, but Lee receives a second chance at life thanks to a zombie outbreak. By meshing together controlled narrative and the core mechanic of player choice, The Walking Dead encourages players to decide for themselves how to define black masculinity through their actions.

We can see how games encourage players to learn and experience race as what Anna Everett and S. Craig Watson call “Racialized Pedagogical Zones” (RPZs). RPZs highlight the way that “video games teach not only entrenched ideologies of race and racism, but also how gameplay’s pleasure principles of mastery, winning, and skills development are often inextricably tied to and defined by familiar racial and ethnic stereotypes” (Everett and Watkins 150). Thus, players are encouraged through gameplay experiences and mechanics to accept and understand ideological perspectives about race, and how racism manifests based on how games model the world around us. Two prominent examples illustrate how The Walking Dead models Lee’s race and encourages players to both respond to and construct Lee’s black masculinity.

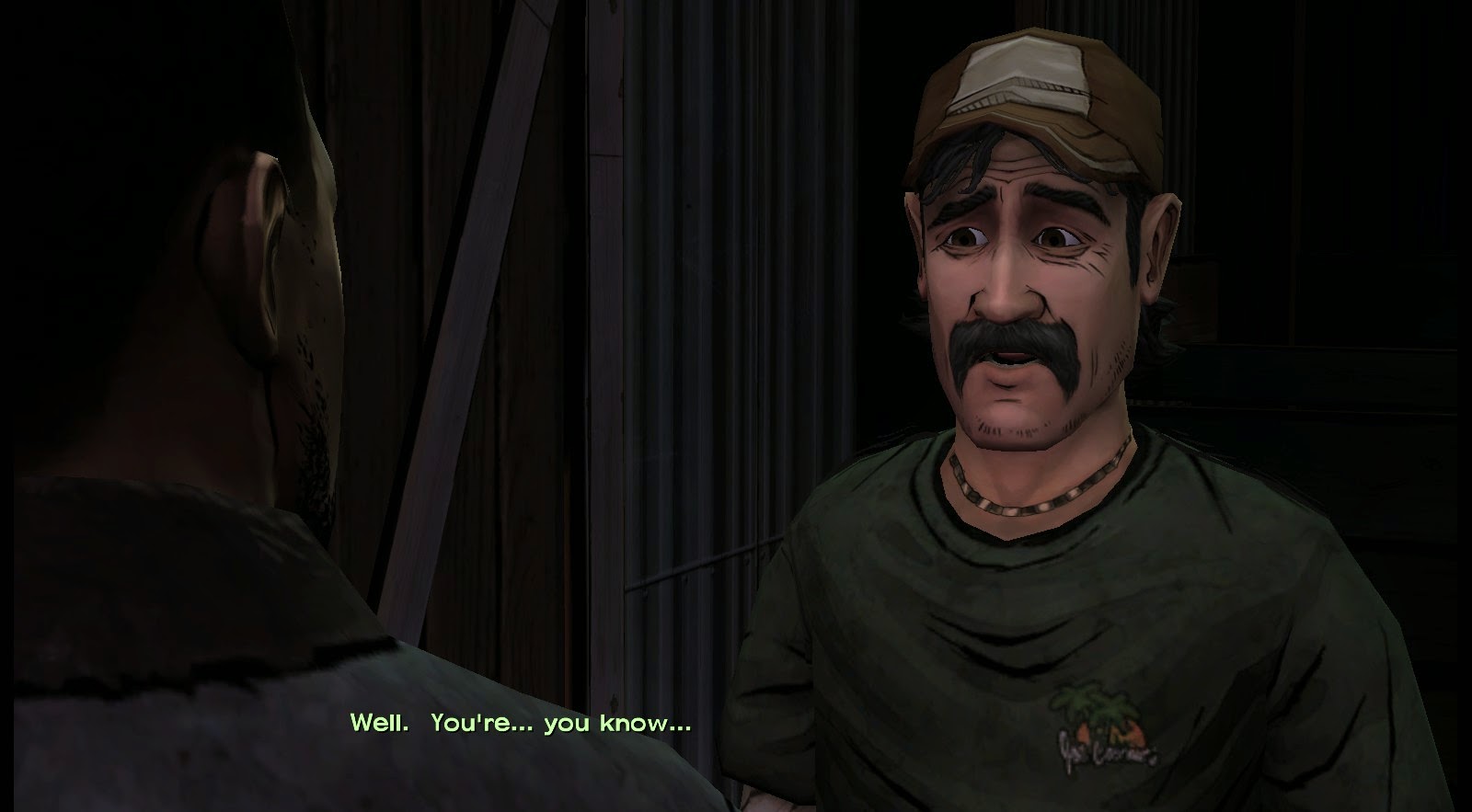

Early in season one, players meet a southern man named Kenny who exhibits subtle racism in his interactions with Lee. In the second episode, upon encountering a locked door, Kenny suggests that Lee knows how to pick locks, because: “Well. You’re… you know… urban?” In this case, the player has no direct control over Lee’s response, and he fires back: “Oh, you are NOT saying what I think you’re saying.” Moments like this strip the player of choice and force them to acknowledge what the developers call the “social facts of the American Southeast” (qtd in Augustine) and factor them into how they define Lee, his gender, and his race. We see that dynamic unfolding here with the player being forced to acknowledge that racism is, in fact, a part of this world and Lee’s interactions in The Walking Dead.

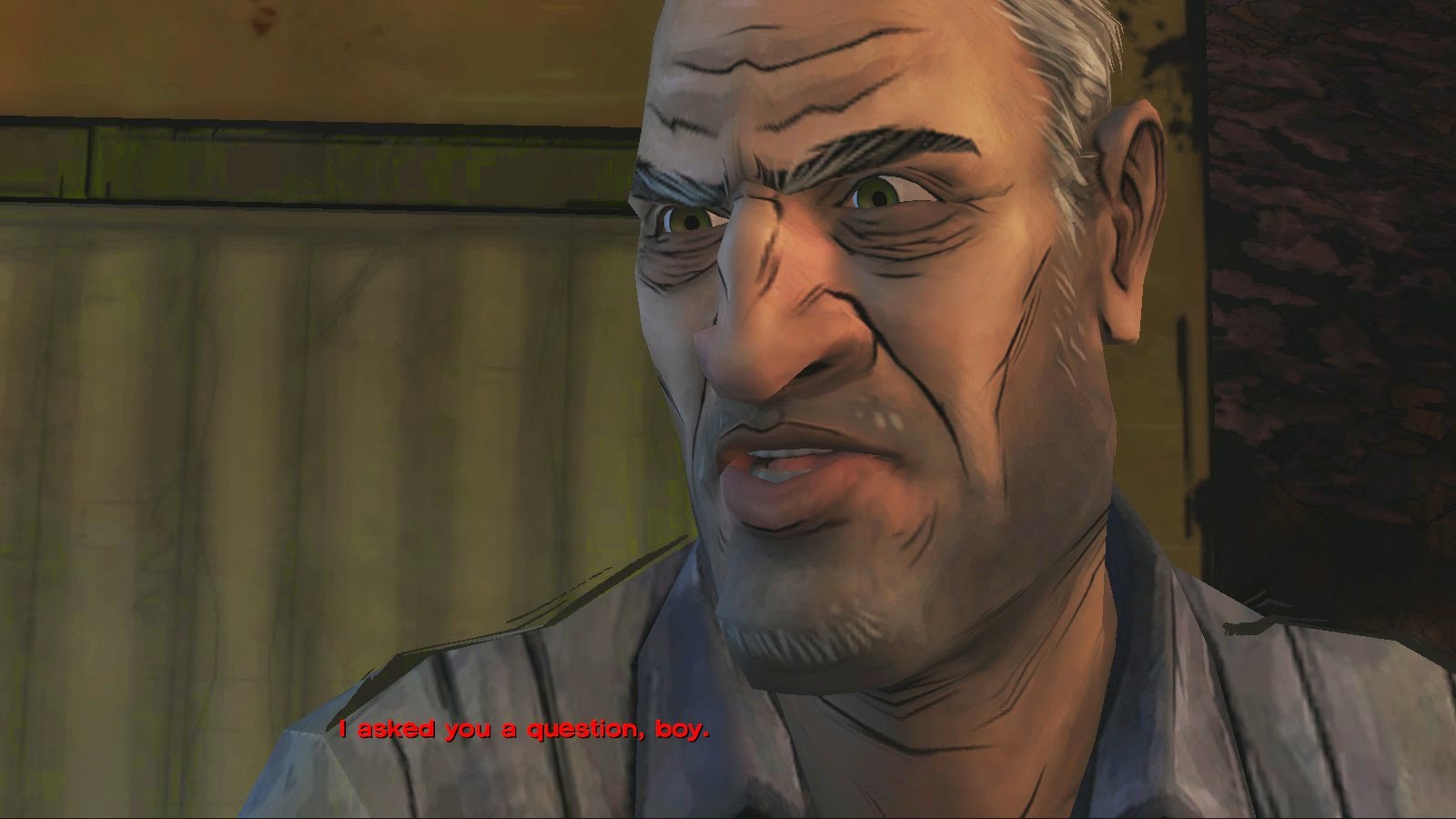

Another important example that feeds into the player choice mechanics starts unfolding in the first episode with Larry. Larry is introduced as a hot-headed, hyper-aggressive older white man who distrusts Lee. By the end of the first episode, it becomes clear that Larry has a racial prejudice against Lee— before the episode’s end, he physically assaults Lee, and later asks whether or not Lee likes his daughter, Lilly. This is followed shortly thereafter with Larry telling Lee: “I asked you a question, boy.” Larry is made an ever-so-slightly more complex stock racist character by only making racist barbs at Lee in passing, but also by contextualizing his concerns through his daughter. It is clear, however, that Larry is concerned about the possibility of Lee, a black “boy,” interacting with his daughter in any capacity. Players are given a chance to respond to another character about how they see Larry through a dialog choice, one of the main areas player choice manifests in The Walking Dead. When asked why Larry seems to dislike them so much, players can choose to reply with more benign comments like “I have no idea,” or a more pointed “he’s an old racist asshole.” Lines like this confront the player with the role of race and racism in this world, and force them to make a choice about how they perceive it simultaneously.

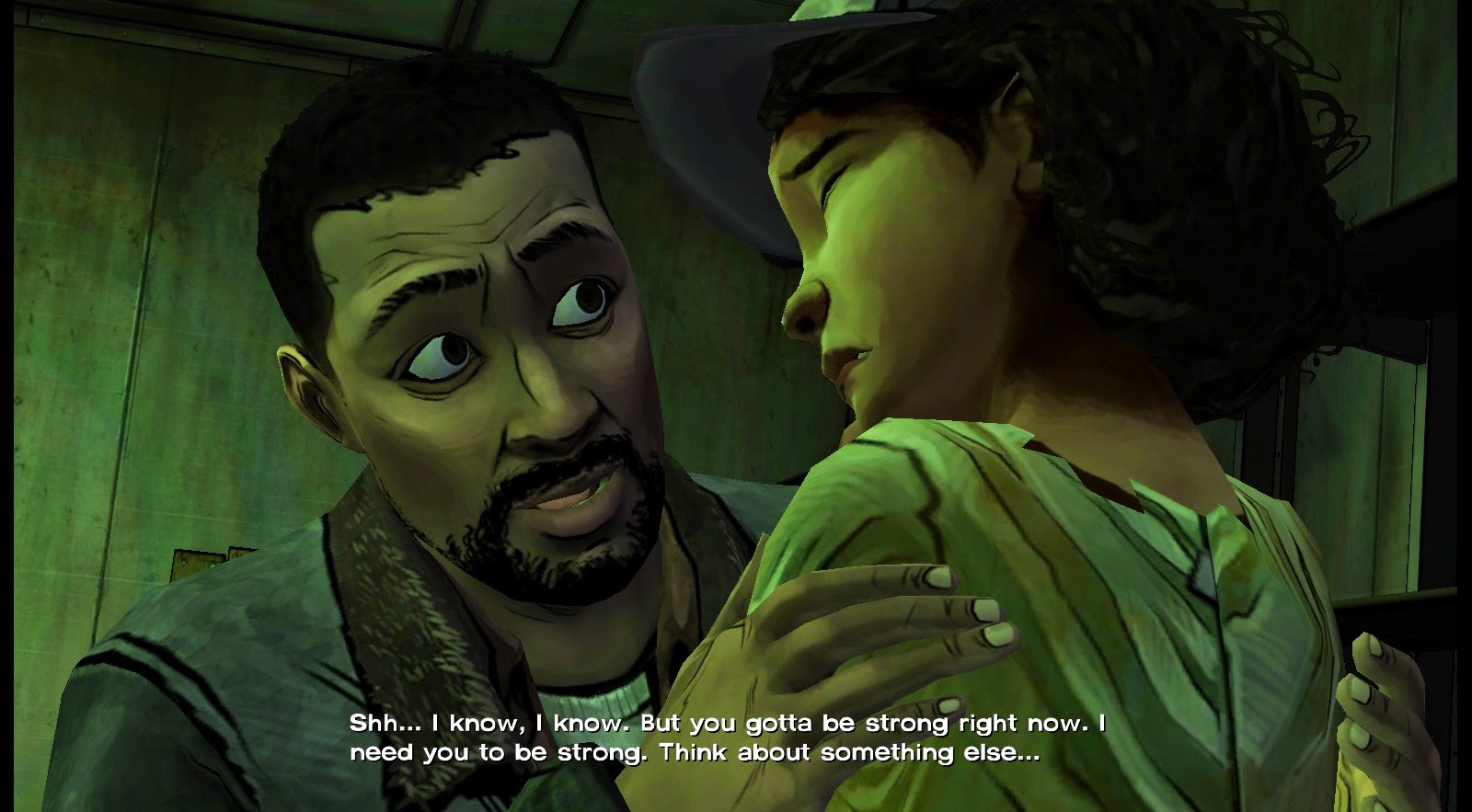

Beyond firing back verbally, players also have a chance to enact a more visceral form of revenge against the antagonistic Larry later in the second episode. The chance for revenge, however, comes under the watchful eye of Lee’s companion and surrogate daughter character, Clementine. Clementine is a young mixed race girl and the starring character in the second season of Telltale’s The Walking Dead who the player indirectly shapes through their actions as Lee in season one. This adds another layer of depth to the player’s interaction with characters like Larry— players must decide not only how they respond to physical attacks and racial slurs from a white man as a black man, but also as a father figure to a frightened young girl searching for her parents. By forcing players to experience and acknowledge racism through other characters and making them respond with their choices, The Walking Dead allows the player a great deal of agency and make the experience of “playing race” in this Racialized Pedagogical Zone far more complex than it is in many other games.

Whereas games like Grand Theft Auto requires the casual murder of other characters, The Walking Dead sets these moments up as crescendos where players controlling Lee have the agency to decide how they wish to enact race. Through the choices set up by Telltale Games, players can define Lee’s response to the racism he encounters how they see fit, be it forgiving or vengeful. In my first playthrough, I found Larry’s abrasive attitude towards Lee (and me by extension as The Walking Dead welcomes players to embody this role) overbearing and chose to enact revenge on him when the opportunity arose. I did not, however, reflect on how this action shaped Lee as a black male, his surrogate father role with Clementine, or how the rest of the group might respond to him afterward. Upon replaying the first season with Everett and Watkins’ notion of Racialized Pedagogical Zones in mind, however, and picking up on the subtleties of the racism projected by Larry and Kenny, I became conscious of how Lee’s actions shaped a young girl under his care, as well as shaping how the other white members of the group he travels with might perceive him and his race through these actions. While being black is not Lee’s main character trait, it is still a vital part of how players experience this world, and serves as a tension players must wrestle with as they play The Walking Dead, consciously or not. Considering games as Racialized Pedagogical Zones, however, allows us to consider not only how race is constructed across a range of games and mechanics, but also to play games like The Walking Dead and consider how it encourages, and in some case forces, us to experience and construct black masculinity.

As noted by Leonard among others, videogames afford players a unique opportunity to engage in what essentially amounts to blackface without public performance or consequences. By “bypassing any economic barriers of travel and societal stigmas, video games provide daily opportunities to try on other bodies and experiences. Whereas tourism allows individuals to ‘indulge in the other’ because you are on vacation only once, video games offer a similar experience without any consequence or cost” (“Live in Your World” 5). In many cases, this chance to insert one’s self into the role of the black “other” with “high-tech blackface” is used to support stereotypes and culturally held beliefs about how race is constructed and operates through gameplay mechanics that encourage and force players to experience blackness as inherently violent and negative through stereotypical characters and wanton bloodsplatter contextualized as mindless fun in realistic playscapes. These concepts go a step further when considered as Racialized Pedagogical Zones, or places where the player is actually learning something from the experiences gathered while coated in the pixelated cloak of high-tech blackface. The Walking Dead deviates other titles featuring black main characters in important ways that allow players to experience, construct, and assess race and racism for themselves. Rather than using the main character’s race as a ticket to ghettos and inner cities where players don a crude blackface meant to reinforce and require players to see the height of blackness as playing sports and killing other minorities or innocent civilians (as seen in GTA and titles like NFL Street), The Walking Dead uses its first episodes as a platform to establish mechanics and character interactions that force players to consider what it means to be black in this Racialized Pedagogical Zone only to move into more active constructions based on player agency.