Panelists

Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, Michigan State University

Laura Gonzales, Michigan State University

Review

In “Remixing the Canon: Rhetorical Tools for 21st Century Composition,” Laura Gonzales and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss challenge us to broaden our theoretical understandings of the rhetorical canon. Gonzales and DeVoss began their session drawing from the work of Cindy Selfe, Steve Westbrook, Collin Brooke, and Diana George, reminding us how “the visual” and “the textual” are typically seen as discrete areas of scholarship and pedagogy. Yet, like Gonzales and DeVoss explain, rhet/comp scholars have been remixing/remediating the rhetorical canons in attempts to move past just print practices.

The presenters used this quote as the theoretical underpinning for their presentation:

“It is time to look to a new mapping of rhetorical activity, one that acknowledges advances in our understanding of language, semiotics, human development, technology, and society” (Prior et al, 2007).

Gonzales and DeVoss use Prior et al to push against the traditional view of rhetoric, which tends to be focused on linguistic texts and producer-centric. Instead, Gonzales and DeVoss encourage us to see rhetoric as a constellating of examples, always multimodal, and utilizing a variety of semiotic resources.

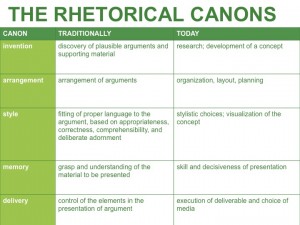

To respond to the challenge posed by Prior et al, Gonzales and DeVoss focus on the intersection of graphic design, civic engagement, and rhetorical theory to reimagine the rhetorical canon. Like DeVoss explained, graphic design scholars have used rhetorical theory to inform their theory and pedagogy. In fact, DeVoss showed an example of how graphic designers have used rhetorical theory in a book entitled, “Design Papers: A Rhetorical Handbook” (Figure 1). Because it is uncommon for rhetoric scholars to take up graphic design theory, DeVoss took this opportunity to encourage reading more of this scholarship, particularly of Ellen Lupton.

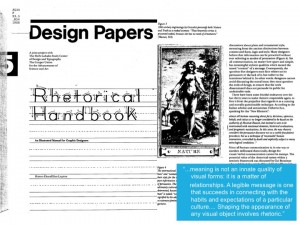

After explaining the reasonings behind why we might consider remixing the canon and discussing how graphic design theory might help us do that, Gonzales and DeVoss presented the following table:

This table underscores the complex, multimodal, and interactive nature of rhetoric. It gives us first the traditional understandings of the canon and then redefines the understandings to be more in-line with our current theoretical understandings and pedagogical practices.

The presenters then used the sites of their own writing contexts — two undergraduate professional writing classes at MSU — as examples of this remixed cannon in action. DeVoss began with an overview of her undergraduate Visual Rhetoric course. In her course, she students first researched their intended productions and then produced their texts based on the research they found. In this process, their meticulous research in the “invention” stage helped them later play with organization and style and eventually create memorable, functional projects.

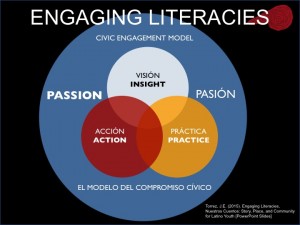

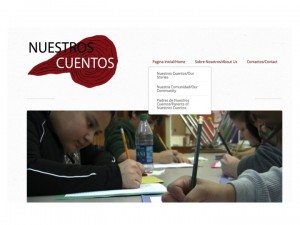

Gonzales then explained how she used this conception of a remixed cannon in her Introduction to Professional Writing course. She began by explaining how we need to combine and adapt the rhetorical cannon with our own communities of practice. Gonzales does this by effectively mapping the remixed rhetorical canons onto elements of the “Engaging Literacies: Civic Engagement Model” developed by Dr. Estrella Torrez at Michigan State University. Torrez defines Civic Engagement through the interaction of passion, action, practice, and insight (Figure 2). Unlike many rhetoric courses that only have the exigency of a writing prompt, Gonzales created a community partnership with Dr. Torrez’s Nuestros Cuentos project. Nuestros Cuentos is a collaborative initiative that connects college students with local youth in Lansing. The purpose of the collaboration is to highlight the histories and stories of Indigenous and Latin@ youth in the Lansing School District. Through this partnership, students in Gonzales’ class both learned from Dr. Torrez and her project and engaged in meaningful projects that allowed them to learn how to build and maintain relationships.

Like Gonzales argued, her students learned to be listeners first and then responders; they listened to the knowledge and needs of the community partner, used their own expertise, and effectively worked across difference. For example, when creating the bilingual website for Nuestros Cuentos, her students ultimately decided to put Spanish first given the primary language of most of the audience members that would be viewing the website (Figure 3).

Students also began seeing the interconnected nature of rhetoric. On a flyer explaining “a day in the life of a student from Nuestros Cuentos” (Figure 4), the students used footsteps as a visual aid to show parents the “path” that a student takes throughout the day. With Dr. Torrez’s guidance, the students plan to share these same footprints at an event designed to let parents experience the life of a student–this time on the floor of the event’s halls–to illuminate both the “path” of the daily life of the students but also the “path” that the event would take throughout the evening. These examples demonstrated how students effectively mapped the remixed rhetorical cannon onto their own practice.

Overall, Gonzales and DeVoss did an excellent job in helping us re-think the way that we have typically theorized the rhetorical cannon — and how we have then used this theory in pedagogy. In thinking about remixing the cannon, along with exploring their examples of students work, it showcases how important it is to see how rhetorical theory intersects with other theoretical constructs. Rhetoric is, like Gonzales and DeVoss argue, embedded in the social, cultural, and material — and we need to continue to re-envision and re-imagine how we might remix our view of the rhetorical cannon to be responsive to that.