Theme: Social Media & Activism

Chair: Rebecca Robinson

Panelists

Rebecca Robinson, Arizona State University

Abigail Oakly, Arizona State University

Molly Daniel, Florida State University

Tracey Hayes, Arizona State University

Review

This very enthusiastic and engaging panel discussed a variety of theoretical underpinnings for using social media in composition classes, and offered models of class assignments and activities (and critiques of those models) using social media as a tool for learning and as the subject for analysis.

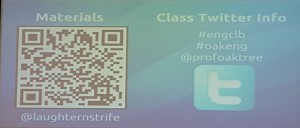

Abigail Oakley and Rebecca Robinson teamed up to present their use of Twitter to enhance their collaborative writing and learning environment. Their presentation materials included a Q code for accessing more information. They noted that they began their search for ways to encourage out-of-class interaction with and among students by looking at pedagogical research. They also highlighted the results of studies presented by Junco et al on using Twitter to enhance student engagement, and listed their goals for their classroom Twitter project. Oakley and Robinson used the 7 principles of good practice from Chickering and Gamson to evaluate the effectiveness of their introduction of Twitter into the classroom.

Oakley and Robinson explained their assignments and the Twitter component that they set up for students. The class was asked to analyze a public apology presented on social media. After setting up their own twitter accounts for class, students were to write at least 2 tweets per week and use collaborative hashtags for each tweet.

As it turned out, the student engagement wasn’t as robust as they had hoped; a review of student participation in class Twitter activities showed student tweets tended to be very general in nature, and less frequent than assigned. As a result of this mid-semester evaluation, Oakley and Robinson tried some new tactics, including live tweeting during class sessions. Still, engagement lagged behind what was expected. Comparing their experience with the class described in Junco et al., Oakley and Robinson found some key differences that could explain discrepancies:

The pedagogical self-reflection here was helpful and informative. Many instructors seem to face the same issues; we see the strong potential for reinforcement of writing and critical thinking skills in social media use, but have difficulty eliciting a strong buy-in from students. Oakley and Robinson made recommendations that definitely seem worth trying:

- Set up common themes and terms

- Find common activities that use twitter functions

- Address preconceptions about twitter culture; model the type of interaction desired

Molly Daniel provided another experience with Twitter in the classroom. She provided a handout rather than a slideshow for the audience. Daniel noted that she had made use of Twitter for 3 years, and that she finds that she is always making changes and adjusting. For her classes, Daniel sets students up in the class twitter account on the first day. One interesting note was her observation that students from earlier classes still visit the class twitter and offer encouragement to succeeding classes.

One other key point was the importance Daniels placed on hashtags, which she described as a rhetorical situation illuminating and facilitating the circulation of ideas and arguments, helping to create an audience.

Daniel, like Oakley and Robinson, used a live twitter feed for class. She made this a regular feature, with the Tweeter of the Day leading online discussion for the 1st 15 minutes of class meetings as the feed scrolled in front of the class. This exercise, she found, warmed up the class for verbal discussion. Daniel also noted that she used questioned posted by students on the class twitter feed for exam questions; students were thrilled to find their questions used for the entire class. This definitely sounds like a useful feedback and response loop to foster engagement with the class. To make it easier for students to follow and connect, Daniel storified the class feed each week.

Daniels described her final assignment, which involved students choosing a cause or event to cover on social media and expand its audience–in other words, go viral.

The final presenter, Tracey Hayes, analyzed the co-option of the #mynypd hashtag by activists. She began by addressing the argument over “slacktivism”–whether online, social media activism accomplishes any results–by pointing out how often targeted regimes shut down or attack these movements. She noted that we have to look beyond binary definitions of success. Not all movements, online or otherwise, can topple a regime, but they can create and motivate publics as they organize and coordinate activity. In the case of #mynypd, for example, Hayes argued that Twitter, and the #mynypd hashtag, became the site of protest itself, subverting the intention of its creators. In April, 2014, NYPD started a campaign to burnish its image, asking people to tweet pictures of themselves with NYPD officers. The hashtag was taken over by sarcasm and images of police brutality. As Hayes notes, the creators of the #mynypd hashtag failed to anticipate the rhetorical velocity of the medium and the publics it would attract.

Hayes explained the 7 features of “a public” described by Warner, and also looked at Gee and Hayes’ 15 features of “affinity spaces” from Nurturing Affinity Spaces and Games Based Learning to explain how this all happened. Since there is no gatekeeper in this medium, anyone can be a producer as well as a consumer. When an unanticipated public begins participating and responding rather that merely absorbing, they can exert control over the message. The result was appropriation and subversion..

To conclude, Hayes pointed to other potential spaces–such as #bluelivesmatter–and noted that researchers in the field need to work on collecting data and harvesting material from these online sources.

The Q & A session started by asking about Institutional Review Board and ethics issues. Panelists noted that IRB requirements are often behind the times when in comes to public, online material. In the examples presented, students were given the option to open accounts devoted to class tweets and keep them from the general public, but 2/3 of the students who already had personal accounts decided to keep them. The issues of student release or permission, collection of tweets, and use of student tweets are still fuzzy. This can take on more urgency with international students; in some countries, citizens are not allowed to use some of these platforms, and what they say online may be monitored. Extra care needs to be taken with these students to make sure they understand and monitor content and privacy settings.

Another question addressed the issue of instructors participating in protests or activism themselves. Could this lead to trouble, especially with an online record? Daniel noted that she had participated in online debate over her university’s presidential search, but that she had to be very careful–as most of us would be.