Title: The Data Drive

Author: Daniel Kolitz

Publication: Useless Press

Release Date: August 3rd, 2015

Website: http://www.thedatadrive.com

When researching and practicing digital rhetoric, as in all disciplines, it is often far too easy to forget to aim one’s critical lens not only at the rhetorical content of the platform in question, but also the platform itself. This is only natural (whatever “natural” means), and applies to more than just the digital; in fact, many have argued that a good text—again, whatever “good” could possibly mean—is so engrossing that the means of its delivery seems altogether transparent. If it is not natural to forget the medium, or platform, or channel, then it is at least “good” by this account. When watching whatever iteration of Star Wars is in the theater, it is good to forget the theater; when listening to Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood,” or watching the music video on YouTube, it is good to forget the speakers, the screen; when reading To Kill a Mockingbird, it is good to forget the book itself—or the Kindle, or the Laptop, or the iPad, or whatever device being used. And when sharing your thoughts, celebrations, arguments, feelings, milestones, animated gifs, videos, quotes—every little detail of your life to a group of friends or followers—it is good to forget the platform itself. It is good to forget Twitter. It is good to forget Tumblr. It is good to forget Reddit. It is good to forget Facebook—and, thank goodness, most of us have forgotten MySpace.

But good for whom?

Our Webtext of the Month, The Data Drive, created by Daniel Kolitz, follows in a long line of texts that purposely increase the opacity of a medium in order to render visible its very real effects on the audience; and if it does not answer the question “good for whom?” it at least prompts the audience members to ask it themselves. A thoroughly political work, you might call The Data Drive a parody of Facebook: it exaggerates the often invisible facets of the platform in order to magnify the somewhat frightening seams that bind together what seems to be a seamless experience. This is strikingly done, at first, by the way in which The Data Drive is visually composed: each section was constructed on pieces of paper, much like collage, and then scanned as a digital image to be used for the text. The effect is immediate: instead of the clean, CSS-driven interface of Facebook, which either frames elements in crisp right angles or hides elements altogether, The Data Drive exposes the cut-up logic of Facebook (and web design in general) by highlighting the rough, uneven edges of the pieces. Of course, The Data Drive uses that very same logic, given the modular nature of HTML, CSS and JavaScript; but instead of passively using it as a principle of design that is rarely acknowledged by the average user, Kolitz makes it explicit.

On its own, the visual assemblage is spectacular enough—but the real critique lies within the interactivity and parody. Perhaps the first thing noticed is the proliferation of advertisements, one of which promptly pops up and, when closed, immediately opens an ad for the same thing: “Facebook wants YOUR story.” With a bit of clicking around, you learn the backstory: Mark Zuckerberg has run off with all of data the company has collected over the years and is now in hiding, using a variety of disguises. The new Facebook CEO, a surly Texan cowboy-slash-mattress-salesman-slash-cartel-leader named Buck Calhoun, needs your help not only to find him, but also to recreate all of the lost data through the newly designed social network, The Data Drive—and, of course, with donations too. Replacing what some might call the sleazy practices of Facebook (like this, or this, or this, or this, ad infinitum) with even more sleaze, Buck Calhoun is here to save the social media day, while Zuckerberg trolls the world with the wealth of information he stole once with Facebook, then stole again from it.

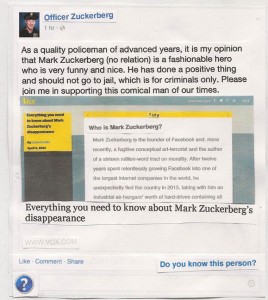

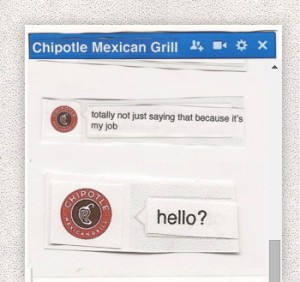

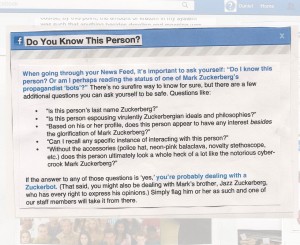

Okay, okay, “stole” is a harsh word. But the point is clear: social media is a dangerous game, and even with its dark satire, The Data Drive doesn’t even compare to the subject of its parody in nefariousness. For instance: Kolitz was not even aware of the fact that Facebook had paved the way for corporations to privately message users, and yet one of the first elements to pop up on the screen is a chat window with Chipotle (who seems a bit stalkerish, but then again we are talking about a platform that sometimes knows more about us than we know ourselves). And then there is the parody of the “Report this Post” button that so many people use and abuse, except on The Data Drive there is a particularly paranoid twist: “Do you know this person?” When clicked, a window pops up that suggests quite plainly that the person in question might in fact be Zuckerberg himself, the Leon Trotsky of social media—who that leaves to be Joseph Stalin, we’ll leave up for debate. Instead of friends, we have a thousand eyes waiting to report us, to envy us, to watch us make the slightest misstep—a parody that sometimes, though not always, might be more “Facebook” than Facebook itself.

All in all, you could spend a good hour on The Data Drive and still have much to explore, and to describe every detail here would be to betray the intent of the text in the first place. The point is to read it, experience it

yourself—or, perhaps in this audience’s case, the point is to assign it. As far as multimodal compositions go, The Data Drive excels as an argument, and its execution is uncomplicated enough not only for students to navigate, but to model their own work on: with some paper, scissors, a scanner and a little bit of html (and yes, ingenuity), any number of webtexts can be parodied, critically dissected and argued in a unique way. And perhaps it is about time that all of us, students and teachers of rhetoric alike, digital or not, start to be more critical of that which we love, which we study, which we use five, ten, a hundred times a day—not so that we can stop using social media (I dare you to try to stop me!), but so that we give the dangers thereof more than a token nod and then a sweep under the rug. It is webtexts like The Data Drive that push us to remember what is so easily forgotten (what is so purposefully hidden): that these texts, platforms, interfaces, channels and media lay on top of problematic foundations. And although we like to congratulate ourselves for already knowing this, it never hurts to have a perfect reminder every so often; and it never hurts, every so often, to remind our students of the same.