Right around the time that we started discussing the theme for our newest blog carnival (Makerspaces and Writing Practices), queer, crafty friends of mine shared with me Melissa Rogers’ project on Hyperrhiz titled “Making Queer Love: A Kit of Odds and Ends.” I was eager to see how Rogers theorized “crafting” and what it might bring to our upcoming conversations about “making,” which often tends to be dominated by robotics, metals, circuits. Rogers’s work raised some really important questions for me about people invested in both crafting and making–and what it means to bring them into academic spaces. Her work explores what happens when we “make” love in a material sense, provides an important perspective on the challenges of documenting making and crafting, and helps us see beyond circuits and wires when it comes to the concept of making (though Rogers does her fair share of electric crafting, which you can check out on her website).

Making Love

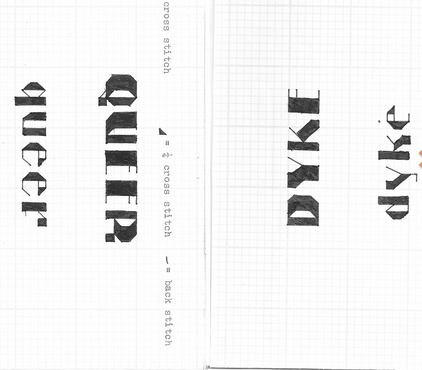

Rogers’ project consists of mailing small kits with thrifted cross-stitch material and a zine with queer patterns and poems to queer crafters to both strangers and friends. A particular focus of the project is to explore what it means to make love and to consider the construction of love, especially in queer ways. As she puts it, “[t]hinking about lovemaking as a project in much the same way that the execution of a craft kit is a project draws attention to making love as a kind of labor that requires the investment of energy, time, and material resources.” The reframing of love, and queer love in particular, as something made collaboratively, something that takes time, and something that is material gives us insight into the social and rhetorical impact that making and crafting can have more broadly.

Though making love is a highly personal act, Rogers’ project seeks out queer feminist crafters that she both does and doesn’t know. Mailing the packages to queer feminist crafters she admires but doesn’t know personally stitches together these different communities spread across time and space. Maker spaces similarly seek to bridge communities and build connections, and Making Queer Love helps us see how the potential work that maker spaces can do can spread throughout a disconnected community. The way that making can accomplish bringing people together across what seem like hard and fast borders reminds me of the work that happens in the space of the Madison Public Library in Madison, Wisconsin. Spaces like the Madison Public Library’s Bubbler bring in artists who work to bridge disparate communities in Dane County and show how making can be a bridge to bring about greater change. For example, projects like ARTinside: filling spaces fill empty spaces in Dane County’s Juvenile Detention Center to connect the broader community to the issues that youth in the detention center face.

Documenting Making and Crafting

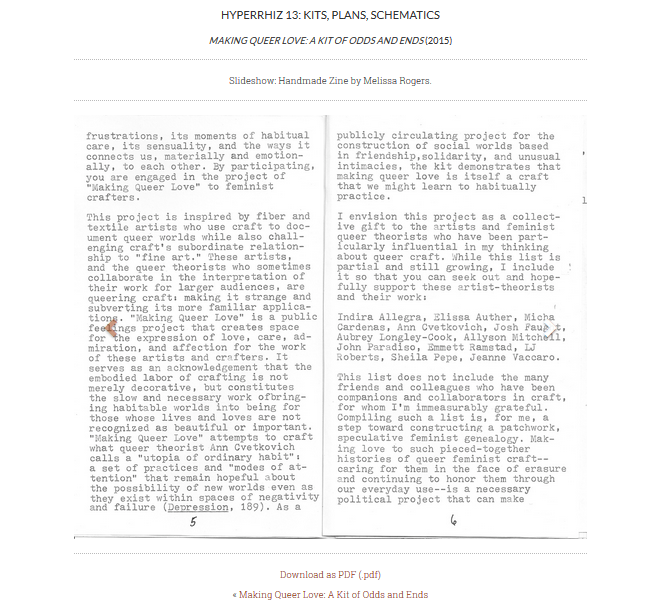

In addition to offering critical insights about queer craft and making, Rogers’ work shows a new way of documenting and experiencing academic work in digital journals. The project unfolds over a series of webpages, divided into components that guide the readers’ experience (I recommend taking a moment now to flip through the project over on the Hyperrhiz site). The page “About This Kit” offers readers photographs of the kit in a series of detailed shots, including a photograph of a partially completed cross-stitch. The staged-but-endearingly-messy collection of decorative odds and ends raises a major question about executing this as an academic project–how do you document the haptics of making and crafting in a flat, visual environment? I wanted to experience the cross-stitching myself, to touch the fabrics and to rummage through the box. Because the design of the webtext invites exploration and lingering, there is a sense that viewers can participate in the project visually if not tactically.

Another challenge in presenting the objects that make up this kit occurs with the representation of the zine. Zines are a genre of writing that should be important to those invested in making — they are texts where the production and distribution of the text is as integral as the words selected. Representing zines in a digital environment is challenging because part of the joy of reading them is flipping through them and enjoying the handmade layouts. Hyperrhiz chose to present Rogers’ zine as a slideshow, open to page spreads. This representation allows the reader to digitally flip through the zine, though the slideshow also automatically turns abruptly at certain moments.

Because Rogers’s work is a kit, the project opens up the potential for the circulation of maker spaces. We often think of maker spaces as places set aside by institutions for the sponsorship of making (perhaps a new way of thinking about Deborah Brandt’s concept of literacy sponsorship in Literacy in American Lives). The containability and portability of Making Queer Love highlights how queer making extends beyond institutional spaces and enter into homes and personal spaces. This seems particularly important for considering the pedagogical possibilities of making and crafting, as teachers are often bound to particular types of spaces.

Craft Supplies, Making Materials

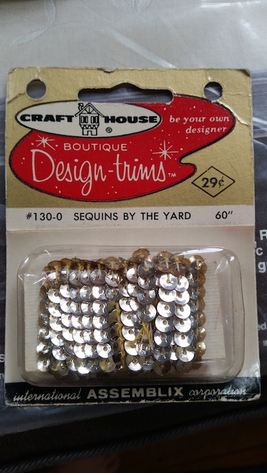

Rogers’s piece asks us to consider what “counts” in maker cultures by attending to the world of craft. Containing materials like thrifted seam binding that proclaims it looks like “pretty underwear” and sequins by the yard that call the recipient to “be your own designer,” the intimacy of the materials within this project challenge the typical plastics and metals used in maker spaces. Rogers aligns this focus “with queer theorists who sometimes collaborate in interpreting their work for larger audiences, these crafters are rethinking and reclaiming the marginality of “low,” domestic feminine crafts such as knitting, crochet, quilting, sewing, and embroidery, using these techniques to make interventions in both the white cube of the art gallery and public spaces.” For people invested in maker spaces, this project asks us to think about how we might more broadly incorporate the potentials of craft materials and challenges the objects we often are oriented towards in maker spaces.

Exploring Making Queer Love helps widen the conversation we’re having about making and its rhetorical and pedagogical potential. I hope you’ll take the time to explore Melissa Rogers’ project on Hyperrhiz as well as her work on her personal website!