What happens when public writing assignments get too public? This question surfaces each time I teach the final sequence of an intermediate writing course where students are asked to engage with writing in public while experimenting with mode. For many students, the thought of entering in and engaging with a public is intimidating, where students learn quite quickly that such rhetorical activity is unstable, temporary, and even volatile. A feeling of publicness—exposure to and within one’s community—rouses rhetorical concerns for how students access a particular audience, which calls them to think about modes. In particular, students must consider which mode meets the needs of that community. This blog post considers how we, as composition instructors, encourage students to theorize and respond to the failures inevitable in doing multimodal work for a public audience when we push students to experiment beyond more traditional forms of textual production.

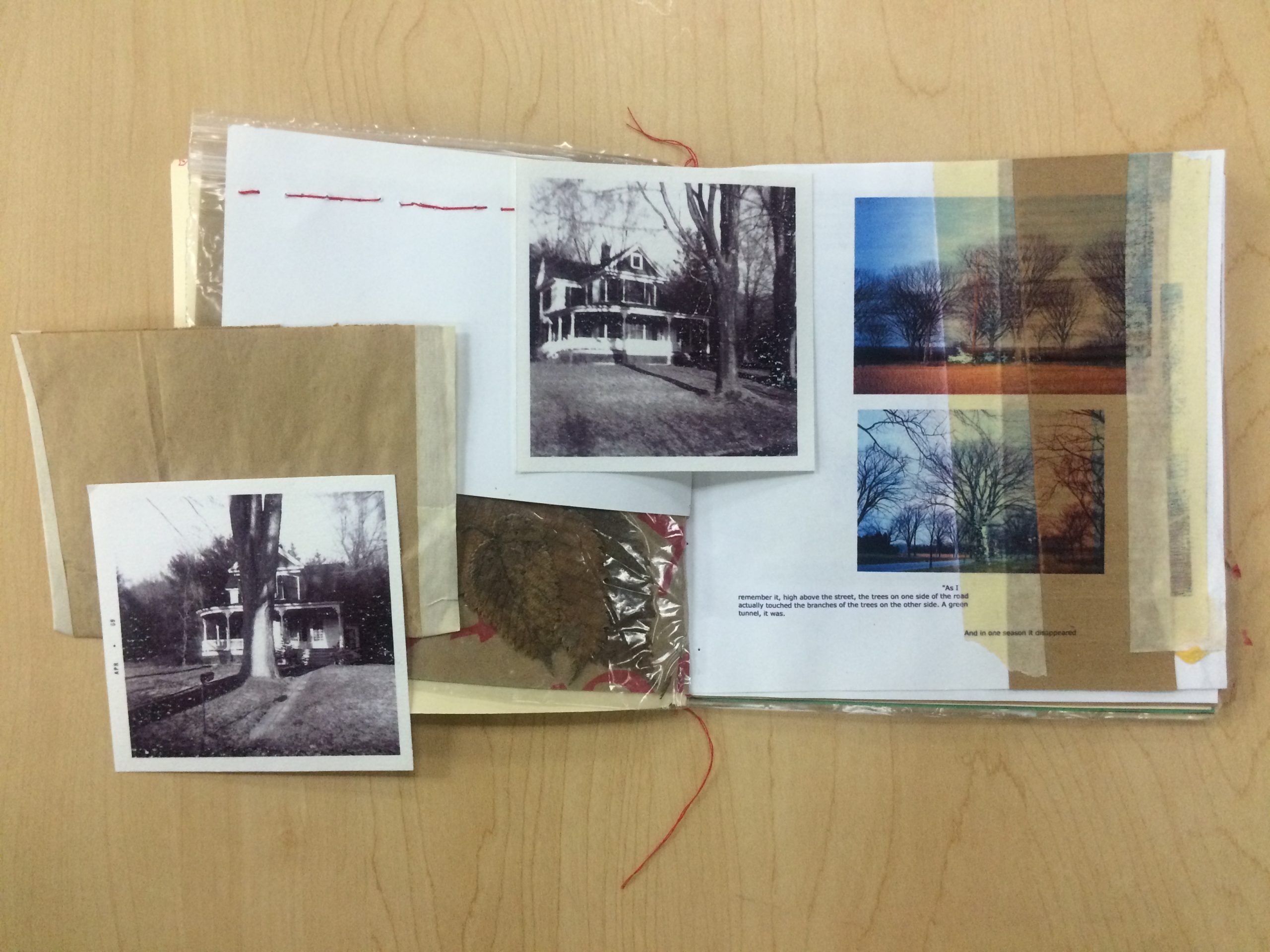

When I first experimented with this final multimodal sequence, I was insecure over the concerns students brought to writing workshops, which caused me to question how the assignment design, through its focus on multimodality, fostered precarious exchanges with diverse public audiences. One student revealed her experiences discussing trans identity with fellow dorm mates while revising her board game, while another commented on the xenophobia he encountered on Twitter for a project arguing geographic locations of debate during the Arab Spring, and one other student exhausted all communicative avenues when contacting local merchants she hoped would partake in her environmental campaign. These students encountered limitations for democratic engagement and questions of technological accommodation that problematized their preconceived frameworks for accessing audiences. While asking students to provide a solution to a cultural problem, these hiccups made me wonder if I had created a faulty assignment design that generated a whole other host of problems inhibiting the goal of practicing rhetorical production.

Although these are only a few of the many experiences students brought to class vulnerable over writing in and with public audiences, the fears of consequential failure connects these students’ concerns—first, the fear of rhetorical failure, compounded by the second fear of assignment failure. As a relatively new teacher at the time, I found myself making accommodations for the assignment worried that I had encouraged risky, difficult, and even hostile public engagement.

Yet I wasn’t left without any hope. I realized that I had to adjust the assessment features of the assignment to allow students to acknowledge where and how failures—rhetorical glitches—occurred throughout their composing processes as a way to mitigate their fear of assignment failure. Borrowing from Jody Shipka, I implemented her Statement of Goals and Choices assignment (SOGC) into my course, which asks students to articulate why, how, and in what ways their project is un/successful within its own situation involving its own set of rhetorical constraints (Shipka, 2011, pp. 110-129). The SOGC calls students to acknowledge where rhetorical failure happens when writing, leaving space for students to demonstrate their growth in rhetorical awareness regardless of the project’s success. Assessment of this assignment weighs such rhetorical awareness first before considering the aesthetic success of the project.

After reading through the students’ responses who experienced the most anxiety with public writing, I realized that instead of accommodating each student’s concern or issue, I had to deliberately reframe the assignment to make it about failure. In other words, students couldn’t avoid the obvious glitches that take place when writing in public simply because writing in public is always precarious—vulnerable, unwieldy, messy, and even hostile. So, I debugged the assignment and restructured the focus to be about theorizing rhetorical failure—theorizing glitch. Doing so allowed students to consider the processes and procedures of arguments—how identification with an audience, technological affordances, or preexisting contextual debates complicate how we write in public. In addition, such an approach to glitching revealed stronger and more authentic orientations to revision because glitching signaled the need to remake—thus revise—an aspect of their argument.

We live in a world dominated by accountability, testing, standards, and assessments. While I am not the first person to suggest the importance of failure in the classroom, I propose refining its use. For my students, the language of glitch helps shake off the baggage of assessment looming when the word “failure” is uttered and instead take seriously rhetorical failure. When writing glitches, the moving parts—an argument, its context, and the rhetorical situation—fail to fit together. I use fit not under the valence of fitness, but rather to imply composition as a set of terms or procedures that merely fit together in writing. When writers encounter glitch they are provoked to revise. In considering where glitches happen in writing, students reroute and recontextualize the failure not as individual blame but rather a larger concern of audience, intervention possibilities, argumentative gap, identification, technological affordance, etc.

Informed by the work of Ian Bogost (2010) and Jim Brown and Nathaniel Rivers (2013), I see value in how the metaphors of procedurality, tinkering, carpentry, and ecologies help foster productive glitching and failing faster in order to see the moving parts of composition. Additionally, I follow Kyle Jensen’s (2014) call to composition instructors to be wary of the mixed messages empowerment can send in traditional forms of process-oriented writing instruction. Students risk assuming autonomous control over their writing under the field’s current dominant model for composition pedagogy, and Jensen calls for new approaches to process-oriented pedagogy that offer students a more critical engagement with the conditions that make literate engagement possible.

I propose that we deliberately make our writing assignments about failing faster and theorizing that failure so students can encounter what meaningful process-oriented approaches to writing look like. In this way, hostile audiences, missed rhetorical opportunities, failed technological platforms represent glitches. Glitches mimic the kind of precarious rhetorical work we encounter in the public everyday. By asking students directly to fail—to acknowledge, encounter, and tackle the moments of glitch that arise when writing—students begin to unlearn the empowerment Jensen warns as a potential risk to genuine writing experience. In this vein, students theorize rhetorical failure as they confront the vulnerability and potential anxiety faced when writing in public with an experimental mode.

Please feel free to visit www.stephanieraelarson.com for more information about this assignment and other courses I teach.

References:

Bogost, I. (2010). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Brown, J. J., Jr. & Rivers, N. A. (2013). “Composing the Carpenter’s Workshop.” O-Zone: A Journal of Object Oriented Studies, 1(1), 27-36.

Jensen, K. (2014). Reimagining Process: Online Writing Archives and the Future of Writing Studies. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Shipka, J. (2011). Toward a Composition Made Whole. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

5 Comments

I love the way you hinge glitching/failure to revision and process-oriented writing instruction. And I think it’s really interesting that in your experience asking students to write to the public is what brought rhetorical failure to the forefront. And that happened in the final assignment of the course when failure followed by revision seems like a crucial component of the writing process. Do you think we need public audiences in order to introduce students to rhetorical failure/glitching followed by revision? Is there a way we can bring these failing/glitching experiences to the forefront while using the classroom and the teacher as the audiences? Or does writing to a public audience create more of pressing need to revise? I am always trying to teach students what revision REALLY is, but I think it needs to be experienced, and that experience like you say comes from failing to access an audience. So my question is, can we provide that opportunity with the classroom as the audience?

Thanks so much for your comment, Annika! Yes, I think we can make glitching an opportunity of all writing assignments. For me, the public audience is what shed light on the issue of glitching, but I think we can expand this framework to all types of writing situations regardless of audience. I started having students incorporate a journal into their writing process that calls them to write each time a glitch comes up while writing. An assignment like the SOGC also helps encourage a deliberate recognition of what worked or didn’t work while writing, and I’m interested to follow Shipka as a model for asking students to fail, document, and theorize that failure.

Great article, Stephanie! Thanks for sharing your assignment and furthering my thinking about “failure.”

I’m always interested to hear how instructors who champion failure design their assessment to allow for it–in other words, grading might limit a student’s willingness to glitch (or perhaps, conversely, create the need to fake/ dramatize a glitch). Is that where Shipka’s work comes in for you?

Also, I’d love to hear more about Jensen. “Additionally, I follow Kyle Jensen’s (2014) call to composition instructors to be wary of the mixed messages empowerment can send in traditional forms of process-oriented writing instruction. Students risk assuming autonomous control over their writing under the field’s current dominant model for composition pedagogy, and Jensen calls for new approaches to process-oriented pedagogy that offer students a more critical engagement with the conditions that make literate engagement possible…students begin to unlearn the empowerment Jensen warns as a potential risk to genuine writing experience.” Are you saying that the field is moving towards an uncomplicated, unproductive cheer for empowerment? Also, is your idea of glitching similar to “writing as recursive,” or are you claiming something beyond that?

Again, I really appreciate your ideas here. Looking forward to incorporating glitching-type language in my class.

Thanks for your comment, Virginia! I can’t say that I think the field specifically is moving towards an uncomplicated, unproductive cheer for empowerment; however, as I read Jensen, his work helps me consider how students can approach meaningful writing situations that acknowledge the constraints of any literate engagement. Empowerment is a bit of a sticky word though, and I’d be more than happy to get together and talk more. And, yes, how you’re thinking of writing as recursive is very in line with a glitch approach to writing—the question for me becomes how do we encourage that recursive practice and build it into our assignment design.

This is great stuff. I look forward to sharing it with my pre-service K-12 teachers and eventually, their students.