How can I make the theoretical critique at the heart of the Introduction to Science, Technology, and Society course more tangible to my students?

This was my driving question as I began developing the syllabus for my STS 214 course at North Carolina State University. One of the assignments previously used in the course was an activity based around inventing a new technology. With this assignment, students worked together in groups to compose a simplified patent application. In 2013, NCSU libraries launched a new Makerspace with the opening of the Hunt Library branch. I had been brainstorming ways to integrate makerspace tools into my research and teaching; when I connected the availability of these tools with the possibilities of expanding the ‘inventing a technology’ assignment, the spark of excitement was immediate. The assignment was expanded so that students would invent new technologies using critical making tools such as micro-controllers, 3D printing, and augmented reality.

Enjoying our work on this project as it progresses. Soon we'll be making music with a Kinect! #ThinkAndDo #sts214 pic.twitter.com/a4kSAlvKKA

— AL-N Kishpaugh (@BBNips) October 8, 2014

One of the main lessons that emerged through this process of invention was that failure happens frequently. An idea for how to make something work might not pan out when using the available tools. I also gamified the course, which lined up quite well with this emphasis on the benefits of failure. In addition to badges, Experience Points (XP), leaderboards (to anonymize posted grades), and levels (in place of letter grades), I emphasized the importance of failure from day one, noting in the syllabus:

Learning from failure: Just as you can restart a level in a video game when you don’t succeed, this course design allows room for failure in a way that won’t necessarily ruin your final grade. I’m going to be asking each of you to challenge yourselves with projects that won’t be guaranteed to succeed. Often learning from failure is just as important as having something succeed.

Therefore, if a particular project or assignment (“quest”) did not work out as intended (or did not generate enough XP), students could either attempt the quest again or write a reflection on what they learned from the process of failure to earn more XP. The XP were ultimately translated back into a final grade. If you’re interested in exploring the concept of gamification and its relation to failure further, you can view a talk I gave at HASTAC 2015 about the topic related to this course.

Inventing a technology was one of the main quests available in the gamified version of this course, and it was divided into four stages, reflecting NCSU’s motto that students “Think and Do”:

1. Research: In this stage they researched their selected critical making tool and reported back via a class wiki with examples of how it has been used so far.

2. Make: After learning about the tools individually, they worked together in small groups to become more familiar with the technology as they followed tutorials to re-create a project that has already been done.

https://www.instagram.com/p/t1HRiiqWUv/?taken-by=sts_bendig

This student won the NCSU monthly Think and Do Instagram contest for posting their project, collecting a GoPro camera as a prize.

#thinkanddo #STS214 pic.twitter.com/vy5vdJd6mI

— Jenna Davis (@jgdavis4) October 3, 2014

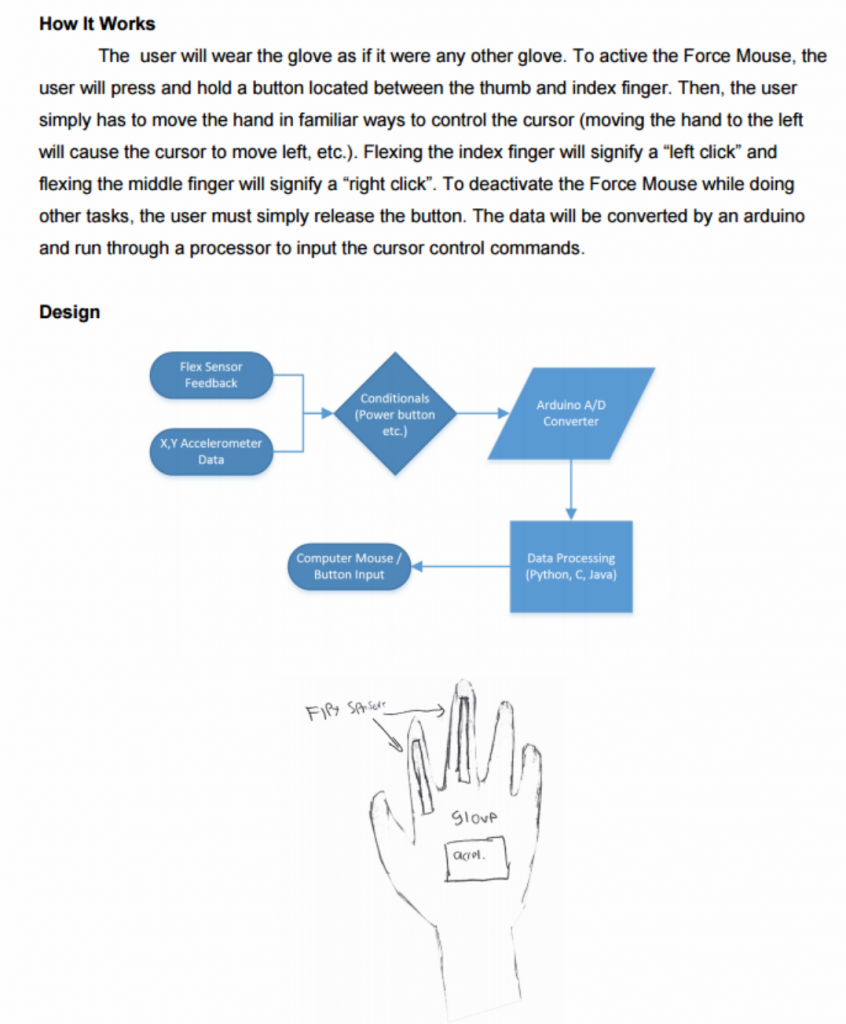

3. “Think” phase: The students brainstormed a new or innovative way to use the technology. They submitted a plan similar to a patent application, that showed how their invention is different from other similar technologies. It also contained drawings, designs, and descriptions of their planned project, which went through an iterative peer and instructor review process.

A portion of of the patent application students created while brainstorming their invention.

4. “Do” phase: Students worked together to bring their invention to life using the critical making tools. They created the invention itself, and a multi-modal project that explained the new invention and how it connected to the theories that they learned in class.

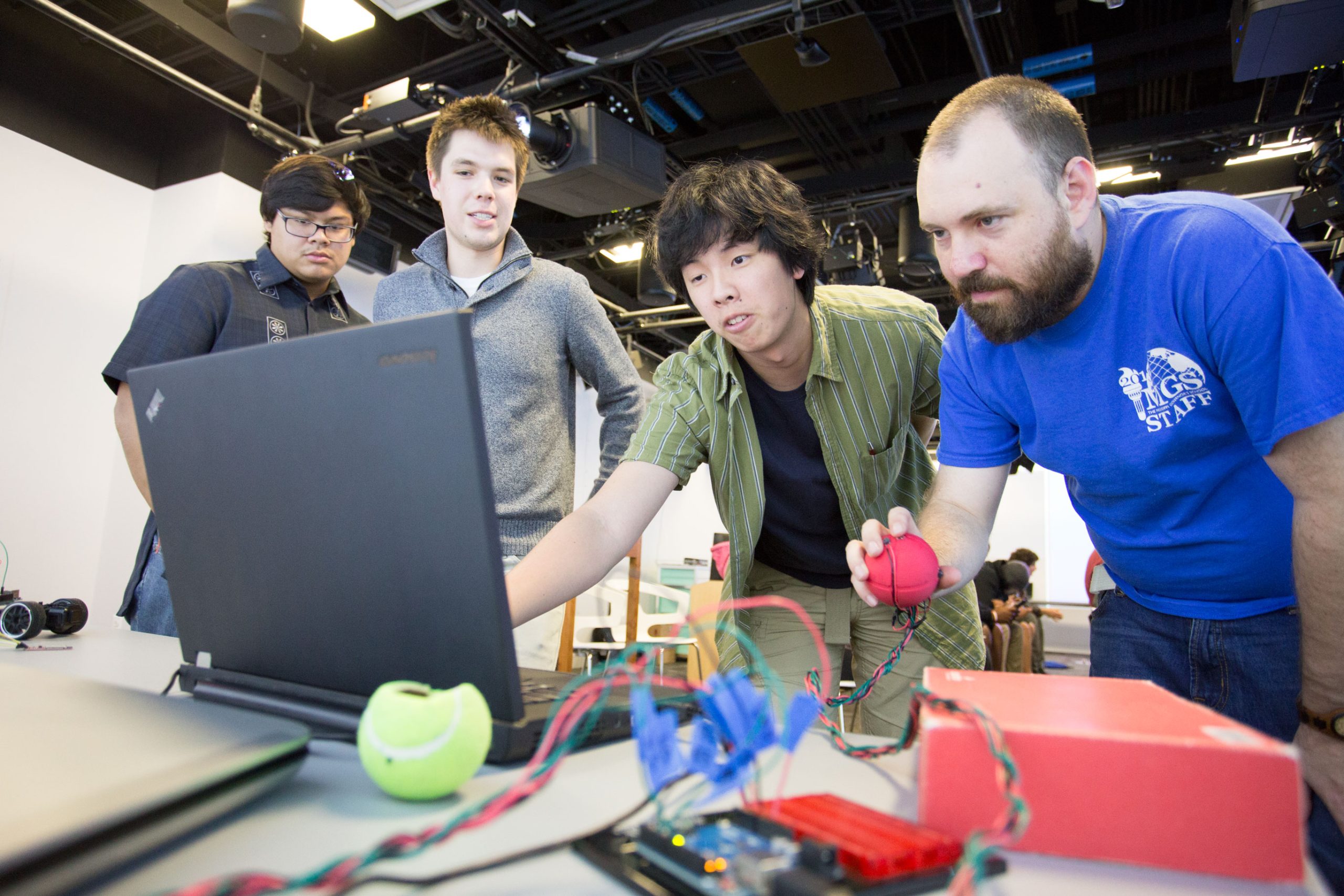

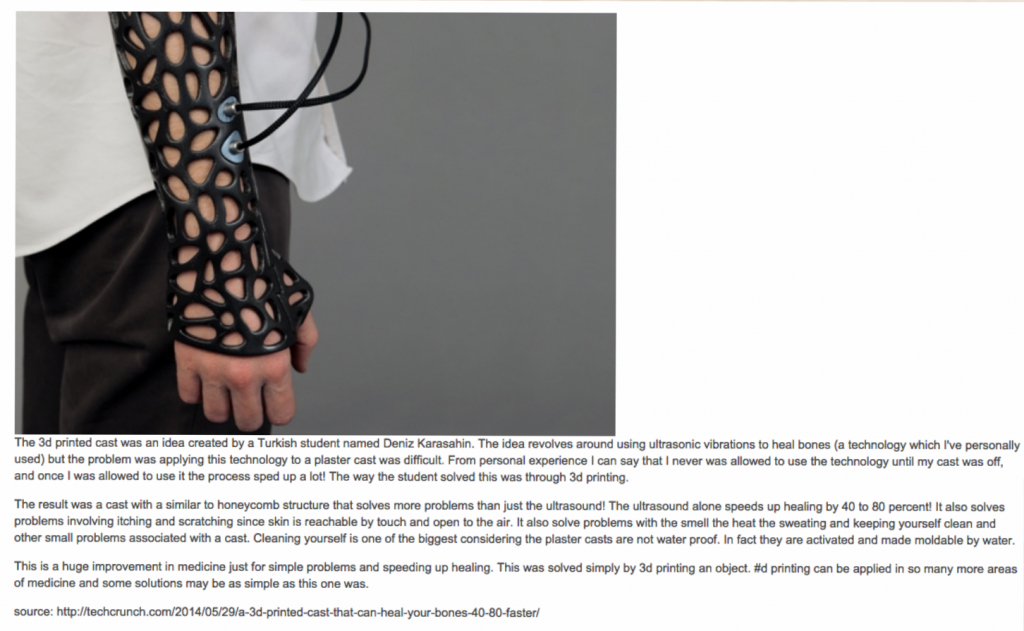

Because I was still learning how to use the critical making tools myself, a close working relationship with the library was important to the success of this project. Our class met twice a month in the library’s Creativity Studio where one of the librarians who worked in the makerspace was available to assist students as they worked on their projects, while I was also available to advise and give direction related to the goals of the assignment. End products include a new type of 3D printed, Arduino-powered computer mouse, a brainwave-controlled remote control car, 3D printed cell phone cases, an augmented reality for music creation, and an Arduino-powered robotic hand.

Images courtesy of North Carolina State University Libraries

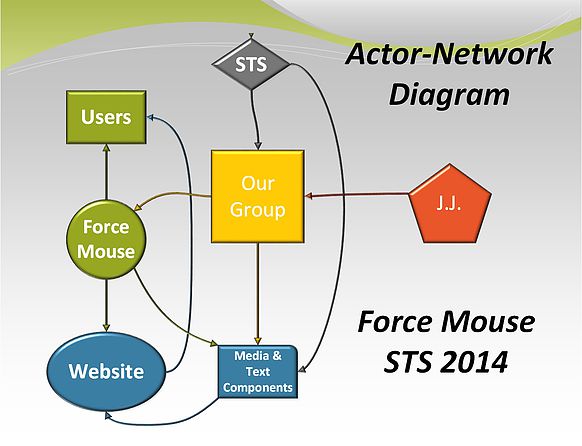

At the end of the semester, students created a multimodal project that both demonstrated their invention and the process of its creation, and then connected it to the theoretical critiques that we had studied during the semester. Many of the groups were particularly interested in understanding the process of invention through Actor Network Theory (ANT), which includes both human and non-human actors as part of a network, without making a methodological distinction between them.

One groups analyzed their project this way:

The production process of this project relied on a complex and systematic network of both human and nonhuman associations. The central unit of this network was our group. As a group through a means of collaboration, creative thinking, and numerous other resources we developed a large network of heterogeneous actors in the process of fabricating our Buds Buddy case. The human nodes that made up this intricate web of actors stemming from our group included most importantly Mr. Sylvia, but also creative studio helpers, other groups, and the minds behind other 3D printing research and projects. These human resources provided information, feedback, production/collaboration systems, and helped stimulate the creative ideas that we needed in order to implement the nonhuman actors.

Another created a diagram explaining the connection to ANT:

Finally, a third group used the concept of the black box to analyze why inventing a new technology can be difficult:

Finally, a third group used the concept of the black box to analyze why inventing a new technology can be difficult:

To an outside viewer, our technology looks very simple. In reality, it is very complex. When we were researching different projects relating to ours we had difficulty reproducing them. We could see what they were doing(input) and what the Kinect was doing in response(output) but we had little understanding of what was happening in between.

Through these analyses, and the emphasis on failure, students were able to conceive of the processes of science and technological invention as active systems open to social input and influence. The use of critical making tools allowed students to experiment creatively, fail, and try again. By actively participating in the process of invention through the use of the on-campus makerspace, students were able to gain a first-hand, concrete understanding of the theoretical critiques of science that we studied throughout the semester.