Introduction

Dale Dougherty once reported that his Make magazine–an early beacon for contemporary “makers” and their makerspace movement–“harken[ed]back to the magazines that hit their peak in the mid-20th century, like Popular Mechanics” (12). According to Dougherty, those 20th century magazines summed a key maxim for contemporary “tinkerers”: “If it’s fun, why not do it?”

As the makerspace movement continues to grow, and as it exerts more influence on education, history can provide other insights into the possibilities of tinkering, and the legacy of makerspaces. In particular, historical makerspaces can provide teachers with examples that include rhetoric and literacy education, which can inform current endeavors.

The Laboratory School and the Clubhouse Project

Under the direction of a young John Dewey, the American philosopher and educator who would author Democracy and Education in 1916, The Laboratory School ran from 1896-1904. Although, in 1900, Dewey was certainly still learning the approach to education that he shared in Democracy and Education –and that has become so influential in the intervening century–Dewey’s school was carefully attuned to relationships between play and work in the curriculum. Likewise, Dewey’s abiding interests in social expression, community, and civic participation permeated the School.

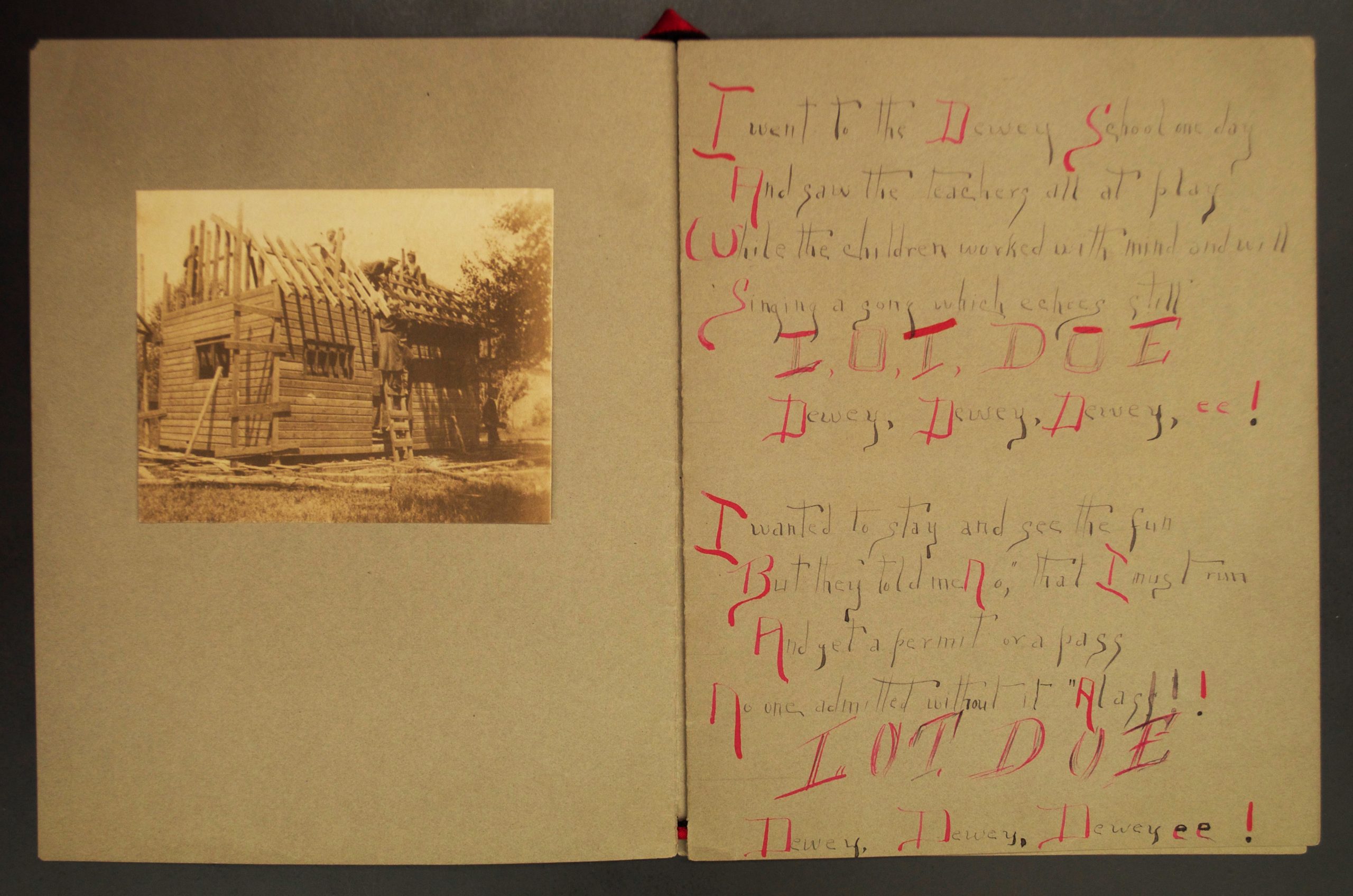

In 1899, the children of the School banded together to build a clubhouse. Originally conceived by the student-run Debate and Camera Clubs, this clubhouse project eventually grew to become the whole School’s project. As the Laboratory School’s teachers later explained, where the instigation of clubs had at first created an “unsocial and cliquish spirit” (232), children came to realize during the building of the clubhouse “the possibilities afforded by cooperation numbers, [and]the spirit changed from an exclusive to an inclusive one” (233). Practical, hands-on building activities were a key element of this transformation.

In our research on John Dewey’s thinking about literacy and rhetoric, we stumbled across archival records documenting the clubhouse project. Following these leads, we began investigating the School itself as a rhetorical endeavor.

In May of 2015, Krysten spent a week immersed in Cornell University’s archives. As she looked at the way the laboratory school had operated in combination with what we were learning about makerspaces, three ideas seem to emerge.

- Makerspaces can involve digital technologies, but they do not have to. Most important is that making should involve richly social, sensory, and embodied problem-solving.

As rhetorical education scholars have noted, focusing “only on digital renders too much else invisible” (Shipka 10). Makerspaces certainly can include the digital, and as Halverson and Sheridan indicate in observations of Pittsburgh’s Makeshop, the digital works right alongside with the physical: “Sewing occurs alongside electronics; computer programming occurs in the same space as woodworking, welding, electronic music, and bike repair” (526). Dale Dougherty also recognizes that we are all makers, whether we are cooking, gardening, knitting (Dougherty 11). While the concept of makerspaces originated in the tech industry, the lab school provides one example of a makerspace that did not involve the digital.That gives us another way to explore these spaces.

- Makerspaces can provide opportunities for students to engage in invitational rhetoric.

Invitational rhetoric facilitates changes that take place “as a result of new understanding and insights gained in the exchange of ideas” (Foss & Griffin 6). Indeed, like makerspaces themselves, invitational rhetoric emphasizes participation, problem-solving, community, and sharing creations with a larger world (Sheridan and Halverson 529).

Mayhew and Edwards write that students initially jealously guarded the clubhouse project. However, as they gradually discussed and opened up their project to more students, those who worked on the clubhouse helped others see value in it.

Along with construction considerations, students also set out to learn rules for organizing meetings so they could conduct their business ethically. When the clubhouse neared completion, students also met to debate who should be allowed to use the clubhouse, and decided to extend an invitation to anyone who had worked on the clubhouse throughout its construction. This invitation marked the realization of the possibilities afforded by cooperation, which helped students revise the spirit of the school “from an exclusive to an inclusive one” (233).

- Makerspaces can help students enact rhetorical citizenship.

As students developed a system around operations of the clubhouse, they began to act as citizens in their particular community. From their observations of young people today, political science scholars and educators R.W. Hildreth and Michael Baizerman conclude that current discussions of citizenship often “miss something very important – they miss the embedded, embodied, and dialectical relationship between doing, being, and becoming citizen in a specific life-world” (112). Additionally, pragmatic scholar Robert Danisch notes that modern emphasis of citizenship is on rights, “but such talk obscures the importance of rhetorical practice in citizenship” (38). Such rhetorical, dialectical, and embedded practice of citizenship was present in the clubhouse. During construction, children formed a club and elected a president, secretary, treasurer, and committees to be made responsible for different lines of work. To conduct their dealings fairly, students also asked to learn about “parliamentary law in order that they might know how to conduct a meeting of their club on house membership.”

For the lab school educators, the clubhouse project represented what we might now recognize as makerspace spirit in action. While their own experiment at the lab school lost some of that improvisational spark over time, teachers marked The Clubhouse Project as one that had special value for their experiment. Today, we can capitalize on that special value by evaluating the clubhouse, and historical projects like it, as a makerspace. After all, as Mayhew and Edwards reflect in a draft for one of their book’s later chapters:

“What was accomplished seemed small even then in the light of what might have been done had there not been so many lacks in the way of equipment, time, and space. Its story, like that of all pioneering in any field, is just the story of the blazing of a trail. It is difficult to tell in retrospect to what degree those children or teachers who participated realized the possibilities… it remains today a hint, only, of a ‘might be.’” (Box 17, Folder 3)

As we blaze our own trails in education, there is value in considering how the history of makerspaces inform what current examples might look like, and how students might navigate within those spaces.

This article was written in collaboration with Jeremiah Dyehouse, Associate Professor and Program Chair of Writing and Rhetoric at University of Rhode Island.

Sources:

Danisch, Robert. “Jane Addams, Pragmatism, and Rhetorical Citizenship in Multicultural Democracies.” Citizens of the World: Pluralism, Migration, and the Practices of Citizenship. New York: Rodopi B.V., 2011. 37-60.

Dougherty, Dale. “The Maker Movement.” Innovations 7.3 (2012): 11-14.

Foss, Sonja K and Cindy L. Griffin. “Beyond Persuasion: A Proposal for an Invitational Rhetoric.” Communication Monograph 62 (1995): 2-18.

Hildreth, R.W. and Michael Baizerman. “The ‘Citizen’ in Youth Civic Engagement.” Becoming Citizens: Deepening the Craft of Youth Civic Engagement.” The Hawthorn Press, 2007,107-122.

Katherine Camp Mayhew papers (6561). Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Mayhew, Katherine Camp and Anna Camp Edwards. The Dewey School: The Laboratory School of the University of Chicago 1896-1903. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., 1936.

Sheridan, Kimberly, Erica Rosenfeld Halverson, Breanne Litts, Lisa Brahms, Lynette Jacobs-Priebe, and Trevor Owens. “Learning in the Making: A Comparative Case Study of Three Makerspaces.” Harvard Educational Review 84.4 (2014): 505-531.

Shipka, Jody. Toward a Composition Made Whole. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011.