For the past two years, much of my research has depended upon my collaboration with Elizabeth Horn-Walker, an art activist who founded the ART of Infertility. This art, oral history and portraiture project works to create embodied representations of infertility through art, poetry and storytelling. As a collaborative partnership, Elizabeth and I travel the country facilitating arts-based workshops and curating community-based art exhibits depicting diverse perspectives of infertility.

At these workshops, we invite our participants to bring objects representative of their experiences with infertility. These instructions have resulted in a range of materials brought to workshops, including: ultrasound photos, syringes, empty pill bottles, pregnancy and ovulation tests, medical consent forms, as well as stacks of medical statements accompanied by insurance notifications indicating denied coverage for these procedures.

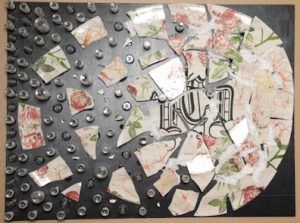

With these materials in hand, participants engage in a reflection contemplating how they may share their infertility story through the repurposing and quite literally – cripping – of these artifacts. Some have made mixed media pieces (like the image “Letting Go.” above) incorporating vials and family heirloom plates to depict the fragmentation they have felt because of infertility, pieces of blackout poetry using medical consent forms for their fertility treatment, others have made empty womb announcements (a play on the typical birth announcement), and others have created pieces of jewelry. This piece suggests that such arts-based workshops aid cripping practices to destablize assumptions and cultural privileging of able-bodied orientations. In the context of infertility, these orientations are often lived through the icon of the neo-liberal family and the systems which reinfoces the family as iconic.

On Cripping

Hutcheon and Wolbring (2013) explain the disabled community’s embrace of the term ‘cripping.’ Like the term ‘queer’ which has a historical negative connotation to it, ‘cripping’ (as in ‘crippled’) is a strategic claiming often made by the disability community to “re-shape injurious words and to describe themselves using language of their choice.” To claim one as ‘crip’ or to enact ‘cripping’ is both a political move and exertion of a particular source of power. Sandahl (2003) elaborates on cripping and its embrace by those who self-identify as disabled that cripping functions as “spin[ning]mainstream representations or practices to reveal able-bodied assumptions and exclusionary effects” (37). I draw on these definitions of cripping first to situate infertility within the context of disability, and second, to explore how arts-based pedagogies can deploy a cripping of cultural assumptions of able-bodied orientations to medicine, technology and composition at large.

Infertility as Disability?

Secondly, my motivation for focusing on infertility is informed directly from the enactment of remediation at an arts-based pedagogical workshops. At these workshops, multimodal narratives are created through the repurposing of medical artifacts to tell stories of embodied failure. As composition instructors we, too, may want to consider how the inclusion of makerspaces may aid similar compositional practices. This I believe is even more imperative because of the increasing call to consider the public work of composition. Composing these narratives of experience serve as cripped artifacts that can circulate beyond the composition classroom and invite our students to intervene in the regulatory rhetorics of ableism.

For the context of this piece, I focus on “infertility armour” a piece made by Elizabeth using needles and syringes identical to the ones her husband would administer to her during her fertility treatment. I argue that the remediation of these syringes serve to crip conceptions of able-bodieness, particularly in the context of heterosexuality and reproduction.

To do so, I articulate how arts-based pedagogies, like those used at ART of Infertility workshops, may not only serve as an ally to crip assumptions of disability but crip the composition classroom itself. Specifically, I speak to (1) remediation as a composition practice cripping normalizing technologies; and (2) how the remediation of artifacts circulates as an embodied translation — making more apparent the invisible operation of disability. I argue that these takeaways are essential to not just teaching students to be critical users of technologies, but to reinvent the space in the composition classroom for student intervention in the circulation of regulatory technologies and their rhetorics.

Remediation: A Composition Practice Cripping Normalizing Technologies

Critical attention to and the study of how technologies mediate student experiences with writing have been taken up in Rhetoric and Composition (see, Why Teach Digital Writing?). Studies have evolved beyond how technologies mediate student experience to critical frameworks to understand how composing is an act of embodied composition itself (Arola & Wysocki, 2012). As composition teachers, we have come to understand the pedagogical imperative for our students to engage in critical understandings and critiques of such technology.

While the scholarly attributes mentioned above attend to experiences our students have with digital technologies pertaining to writing, I see the need to expand the types of technologies we ask our students to critically engage with, especially at the intersections of technology and dis-ability. A cripped framework aids in not just asking our students to critically engage in these conversations, but cripping through remediation allows for critical intervention. As a “re-presentation of material in one medium through another” (Tarsa, 2014) remediation invites arts-based pedagogies to inform a cripped framework and so as to critique and co-opt normalizing rhetorics of ableism present in technologies. I articulate how I view cripping as a remediated practice drawing upon Elizabeth’s infertility armour necklace.

She explains her necklace:

I created this piece of infertility armor using needles and syringes identical to the ones my husband used to give me progesterone in oil shots. The shots were one of the things I feared

most about IVF but it turned out they weren’t as horrible as I imagined they might be. The amber, while a fashion staple for me, is also a nod to the amber teething necklaces for babies that became popular while I was trying to get pregnant. I felt slighted because amber was MY stone and everyone else was buying it for their babies when I couldn’t have one.

For Elizabeth, the re-purposing of the syringes and incorporation of amber allowed her to narrate her experience with infertility. She explains that she was initially afraid of the shots she would have to endure with undergoing IVF. Yet, in her statement she remarks how the shots themselves were not that bad but larger cultural practices were actually more harmful – like the popularity of amber teething rings, a reminder of the baby she could not conceive.

Two examples of cripping as a remediated intervention appear in Elizabeth’s necklace.

1) The remediated necklace crips conceptions of infertility by surfacing how medicine acts as a technoscientific practice. The necklace as an artifact is itself cripped. The decision to incorporate syringes, intended to aid reproduction, no longer are in its intended form. The syringes in its current form as a necklace actually are no longer capable of being used for treatment. They have been re-puprosed, remediated.

2) Western culture’s saturation of biomedical practices, such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF), has contributed to a sense of false belief in medicine’s abilty to “fix” (and even ‘cure’) non able-bodiedness. Take once again, Elizabeth’s necklace. Further reading of her artist statement would reveal that the syringes she used on the necklace are from necklace are from an IVF cycle that ultimately failed with Elizabeth miscarrying twins at 6 weeks.

She writes “Amber and pearls are my go-to gems. While I was trying to conceive, I developed some superstitions. One was that I had to wear amber every day or it may change my energy and decrease my chances of getting pregnant. This was unusual for me because I strongly put my faith in science. However, while undergoing treatment for my infertility, science was letting me down.”

Elizabeth’s artist statement and her purposeful incorporation of amber beads offers an alternative narrative to biomedicalization and the narratives of medical success often attached to it. Specifically, viewers of the necklace are offered a rethinking Western culture’s faith in science/medicine and how frustration can appear when assumed and common medical procedures fail. The remediation of normalizing technologies, like IVF, and their artifacts, such as syringes, is one such example of how artifacts (or in the case of this example ART-ifacts) can function as rhetorical sites of inquiry in critiques of technoscience and biomedicine. The cripped creation of remediated artifacts, like the infertility armour, can aid students in understanding the ways in which, medicine in particular, depends upon rhetorics of normalcy and denies often the narrative experiences of anything that fails to adhere its normalizing rhetoric.

Cripping the Visibility of Dis-ability through a Remediated Arts-Pedagogy

Remediation also expands the potential of cripping because of its accessibility and potential to circulate. Returning once more to the infertile armour necklace. This necklace was created with syringes typically disposed of after use. The physical act of using a syringe to receive fertility treatment often occurs in private. Yet, the remediation of those syringes into a wearable object, such as a necklace, crips in the invisibility of that medical procedure as something private into a public (even wearable) rhetoric.

Further, remediation crips the conflated and false assumptions that disability has visible attributes. Infertility, a disability ruled by the ADA in 1998, speaks directly against such assumptions. In fact, the need to facilitate a cripping of disability using remediation is even moreso needed given the ability to make embodied experiences more visible through the repurposing and circulation of artifacts, like the infertility armour necklace. Positioning remediation as an arts-based pedagogy invites for a more public role of composition by suggesting remediated artifacts can live, circulated, and even worn outside of the confines of the composition classroom. Doing so expands the critical questioning of disability as a rhetorical and discursive site of inquiry to a more public and community-based scene of inquiry.