Presenters

Bill Wolff, Saint Joseph’s University

Devon Ralston, Miami University

Review

Presenting immediately after Stephanie Vie’s keynote on social media’s increasing influence, Devon Ralston and Bill Wolff explored the possibilities for and ethics of researching social media with their panel “The Ethics and Archives of Doing Social Media Research.” Through anecdotes, lit reviews, methods, software considerations, and questions, they challenged the field to view social media research as more than something we should do given its pervasiveness, but to instead position it as something that has extreme relevance and thus requires sensitivity because of its presence in many people’s lives. So, they used their panel to identify how to be careful, concerned, and composed when researching social media.

Ralston opened the panel with a story about the she made over the social media posts that she could and could not include in her dissertation given privacy concerns and restrictions. Building upon that experience, Ralston examined broad ethical issues around researching social media in her presentation “Subscribe, Follow, Share: Research Methods and Digital Activism.” Her primary focus was on the fact that for many individuals, social media platforms are spaces for expressing and exploring one’s own deep and personal involvement with topics and issues they are passionate about. As researchers, then, we must consider our research subjects’ desires and concerns for their posts. Just because a post is “publicly” available on Twitter or Facebook does not mean that the post’s creator is okay with that post appearing anywhere else, let alone our research.

In light of her concerns, Ralston introduced a set of guiding principles for social media research. Getting informed consent from research subjects topped her list. As a concern shaping how one performs social media research, informed consent pushes us to question the the privacy policies of social media sites and what they mean for our work and any potential research subjects. Ralston specifically questioned the policies of many social media platforms which allow the re-publishing of others’ posts. As researchers we should not view these as “informed consent,” especially when we know that many social media users, ourselves included, do not actually read these policies.

Tying everything together, Ralston detailed her experiences with an e-mail newsletter that she wanted to research. She recognized that the newsletter was not public and was also deeply personal, meaning that researching it would bring attention that the writer did not intend for the newsletter. So, Ralston chose not to pursue researching it. Her focus, and she argues our focus should also be, was with research subjects and their desires and plans for privacy, confidentiality, and protection.

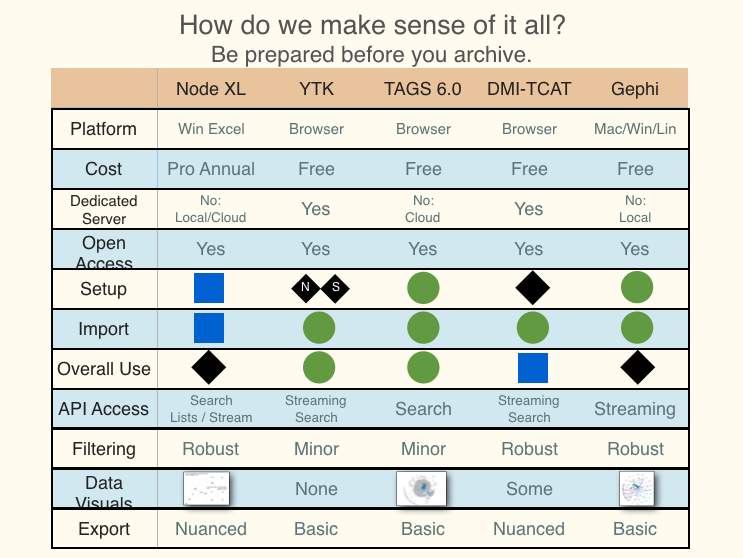

In “On the Decisions, Methods, and Visualizations of Social Media Archives,” Bill Wolff focused Ralston’s concerns through a consideration of the programs that enable archiving social media posts. Wolff both introduced various programs available to researchers for collecting and then visualizing social media posts and provided a list of considerations that researchers should address before, during, and after using these programs. First, he explained that we should be prepared before we start archiving: we should understand the programs we decide to work with and know their limitations, possibilities, demands, and costs. Having worked with several such programs already, Wolff provided the below breakdown that outlines the possibilities, costs, requirements, and skill-levels of a variety of archiving programs:

After reviewing these programs, Wolff positioned each individual archive and/or visualization that he and others had created as a political and rhetorical text, which was generated for the archivist’s goals. So, he challenged us to account for our individual involvement in composing social media archives. At the smallest scale, we should be able to explain our reasons and goals for each archive that we generate. At a larger scale, we should consider the implications of collecting thousands of comments that were a part of (sometimes) continuous, troubling, and/or harmful conversations. As an example, Wolff discussed the archive he built around an ill-advised joke about AIDS in Africa that created an international Twitter backlash against the individual. Concerning his own archive of the incident, Wolff recognized that tweets he made and that colleges made are now stored and visualized within it. Thus, he argued that he, and by extension we, need to continue to be held accountable for our and others’ posts that are collected in our archives. One way to do this is to be, in Wolff’s words, “a good citizen researcher.” Such a researcher asks for permission to publish specific posts, acknowledges those who give permission, and shares their archives when allowed.

While both presentations offered a variety of concerns, questions, and approaches toward ethical social media research and archiving, both presentations did raise questions that could use future exploration. Ralston, for instance, briefly addressed the issue of researching social-media-focused hate groups, which are particularly difficult to research if one seeks to get informed consent. Many of the individuals who participate in these groups deliberately obscure their identities, making it nearly impossible to contact them and/or get them to consent to having their posts studied or be interviews about their writing. So, do we ignore these groups, leaving their vitriol and hate speech unstudied and academically uncontested, which would seem to further the silencing of critical voices that is the raison d’etre for these groups? Or do we need to shift our principles based on who we are researching and reasons for researching them?

Additionally, Wolff’s concerns for our involvement in our own social media archives raised questions about our responsibilities for our own social media posts. Given the rise in community-based social media research and pedagogies, how should we research, archive, and visualize social media movements, such as #hashtags, that we challenged, enhanced, or generated? What about our students, particularly in professional and civic writing courses, who engage and develop #hashtags campaigns?

As Vie noted in her keynote right before this panel, social media is an increasingly important part of our and others’ lives. We need to be researching it, building knowledge and best practices that help us and others understand and address its influence. However, as Ralston and Wolff explored in “The Ethics and Archives of Social Media Research,” we need to pause, reflect, and plan before embarking on this work. Despite the rising influence of social media on our lives, our research agendas and questions might not be shared by those we seek to study. We need to consider, work with, and address their concerns, desires, and ideas. Fortunately, Ralston and Wolff offered a variety of principles, practices, and tools for doing just this.