Linguistic Version

What happens when from inception our compositions honor reader diversity specifically in terms of abilities?

What happens when we reject the notion of transliteration, fashioning translation as foundational to our invention and delivery processes?

What happens when we craft “text experiences,” not just “texts,” experiences that invite readers to determine ultimate meanings? What happens when we release some control of the message itself in favor of greater accessibility (a truly “participatory design”?)?

Sean Zdenek, in User Experience, describes the often “noisy” experience of multimodal, multi media texts. He writes that “…sounds accumulate, overlap, and compete with one another: multiple and overlapping speakers, indistinct and indecipherable speech sounds, environmental and ambient noises…” This articulates beautifully the nature of the video version of “Combinatory Composition” (below); it is “messy” or “rich,” depending on how one thinks about the task of translating the sound and sight experience for someone who needs or prefers information to come through different modes.

Thinking about this richness, or layering, before having composed it, and thinking, too, about how to create valuable experiences communicating “noise”/”richness” in various modes posed fascinating hermeneutic challenges. To meet these challenges, I imagined authoring and offering different versions of a text in one place. Readers could combine versions to create experiences that most suited their needs or that meant the most to them. I call it “combinatory composition.”[i]

This blog is crafted as an experiment in combinatory composition. It began with an imagined audience of various physical abilities and preferences (which isn’t to conflate the two), particularly concerning sight and sound. It began conscious of modal choice making: With what mode should I start? Why? What do I want to say and to whom? What are the most important units of meaning I feel I want to convey right now and how to do that visually, linguistically, acoustically?

What follows are different versions of this text. By combining them, readers might achieve fuller access to the text than one version alone would allow.

**Note: the blog format, and this theme in particular, constrains the potential of this experiment, privileging the linguistic and the linear. An ideal digital space offers versions without favoring one mode over others or suggesting that one format is “original” and thus most complete.

Audio/Visual Long Version

A reader might choose to watch the video version of this text (below) instead of reading the linguistic version, or after/before reading it. The images and sound layers add and alter meaning communicated in the linguistic version. And the linguistic version achieves a different kind of pace, space, and efficiency that contributes to meaning. By experiencing both versions, readers have access to more information and meaning making.

There is no shortage of research establishing that people generally prefer video to “the written word” (commensurate with shortening attention spans). This has interesting implications for the relationship between scholars and the general public, but it also suggests missed opportunities for communication among scholars. We are all humans cyborgs, humans with tech-influenced attention spans. To dismiss the heuristic potential of video production and reception merely to align with long-standing ivory tower cultural norms and imperatives seems a bit futile at best. At worst it denies access to many perspectives that could valuably inform the various ideas explored in the texts scholars offer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDy2vg5o39A

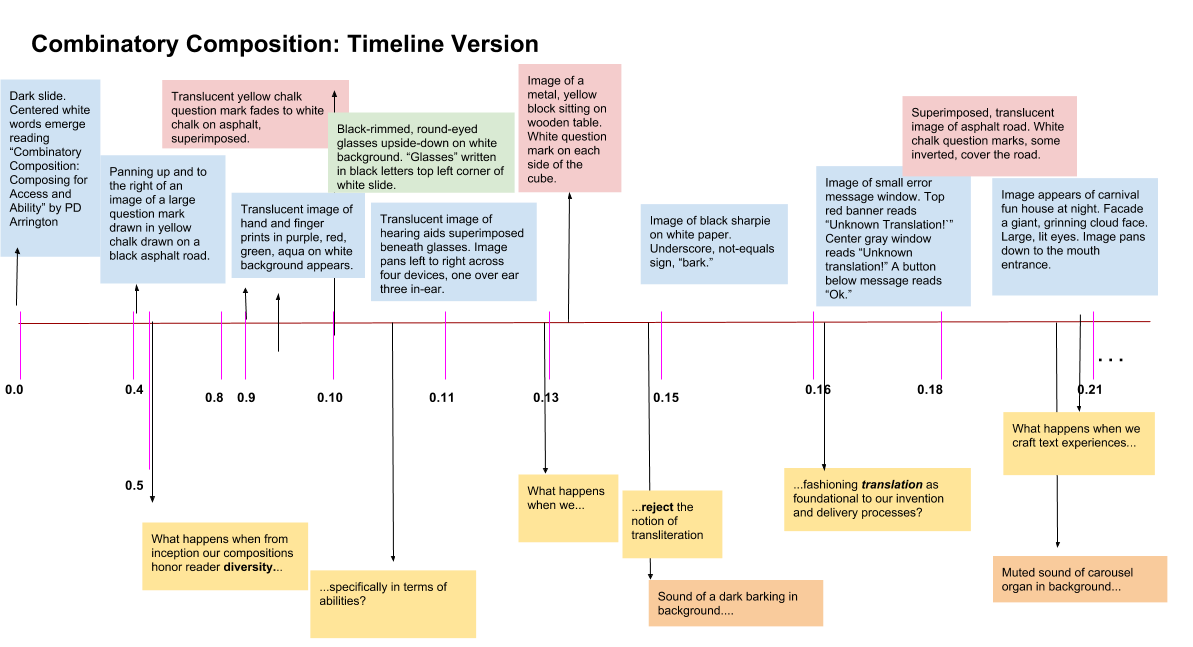

Timeline Version

In an audio/visual experience timing greatly constitutes meaning making. Sounds layer, interrupt, and this experience happens in time with other experiences; captioning alone leaves out much meaning potential. Captioning is not a transliterative art; it’s an interpretive one (see Zdenek 2014). The captioning in the above video, for instance, leaves out the barking noise and the carnival music in favor of the narrated message. If deaf readers are offered this captioned experience and the timeline below, they have access to more information than they do with only the captioned video.

Not only does more meaning making happen during captioning, translating images and sounds in time offers greater meaning potential. A timeline indicating when significant sounds happen in relationship to sights/images/effects, particularly when paired with other versions (say, audio/visual “snippets”) offers opportunity for access to and generation of more information than any single captioning or composing effort.

A screen reader, too, will interpret linguistic text in a timeline uniquely, perhaps voicing a jumbled effect a listener might find valuable. The idea is not to replace the visual aspects of the video, but to offer an experience of relationship, an impression of imagistic layering, to create a simultaneously linear and nonlinear experience. This paired with the audio track snippets (from the videos) offers opportunity for access to information mere narrative description cannot provide.

*Note: This timeline, created in Google Drawings, can be embedded only as an image, which is not accessible by a screen reader. Ideally, an iframe embed of the original file (instead of an image of a copy, like this one) would be easy to accomplish. Unlike an image, the iframe embedded document would be screen-reader accessible. (If there is a way to do this now, this author doesn’t know it yet.)

Audio/Visual “Snippets” Version

Reading the timeline above then viewing the snippets below provide access to sound/sight experience relationships one version alone cannot provide. Ideally these versions are smaller and situated near the timeline for simultaneous viewing, though this blog theme doesn’t allow for such an arrangement.

Audio/Visual Snippet #1: 0.0-0.13

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQQURii8tYY

Audio/Visual Snippet #2: 0.14-0.28

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xo0KaDNsIlo

Visual Descriptions with Timestamps Version

These offer linguistic translations of just the images of the video; essentially they are transcripts of the imagistic video with time stamps. Unlike screen reading the timeline, this version reads without the “jumble” of layered image descriptions. Composing for those who cannot see has been the most challenging, and in some ways most rewarding, experience. Combining a screen read of the linguistic text with the audio “Visual Descriptions” version below offers readers more information and meaning than the single version alone.

Audio “Visual Descriptions” Version of Video Text

Audio Narrative Long Version…

Combinatory composing spirals into possibilities. Note how the audio version here offers a narration of the video, not merely a reading of the linguistic version of this blog text. For every version could itself become an object of translation. And every version communicates a slightly different meaning and meaning potential. So composing for access, in this way, requires adopting a particular consciousness and choice making. What meaning am I making? To/with whom? Why? Which modes do I include? Where do I stop and why?

Challenges

Echoes of Amanda Cachia’s “creative methodological” approach to curating for access at art museums resound in my ideas for composing here. (Thank you to Margaret Price for directing me to Cachia’s work.) In her article “Disabling the Museum” Cachia presses members of the curator community to consider access as an aspect of the art itself, opening great possibilities for curators to expand the power (and meaning?) of artwork (278). Bringing this notion to writing risks revealing our current “art” as reductive and narrow, not just exclusionary.

Of course many valuable ideas—revolutionary ones—develop via writing primarily in the linguistic mode. But access scholars continue to teach us that privileging the linguistic comes at dear cost. Continued dedication of resources toward crafting and communicating primarily in the linguistic mode results in lost human perspectives and a wealth of meaning making that just doesn’t happen, because it can only happen in other modal combinations.

Combinatory composition–writing texts in versions that privilege different modes of communication–favors readers’ needs and agency over writer control of mode and message. By combining a linguistic version of a text, and a captioned video experience of a text, a deaf reader, for instance, has access to more information than just one version alone. A blind reader has access to more information, too, when offered audio versions of texts. But the practice of composing a message in several versions is a hugely constructive process for the writer, too.

This experiment has enlightened me particularly to what we all gain from a universal design orientation. Writing like this feels uncomfortable, but it’s a greatly generative discomfort, with important potential to benefit composers and readers.

_____________________________

[i]Admittedly the last person to ask about mathematics, I’m not sure to what extent this term borrows on combinatorics. I like the description of combinatorics offered on the site “Combinatory Mathematics: How to Count without Counting,” by Professor Hossein Arsham. Arsham writes, “One of the basic problems of combinatorics is to determine the number of possible configurations of objects of a given type.”)Sources

Cachia, A. (2013). ‘Disabling’ the museum: Curator as infrastructural activist. Journal Of Visual Art Practice, 12(3), 257. doi:10.1386/jvap.12.3.257_1

Hossein, A. (2015). “Combinatorial mathematics: How to count without counting.” Dr. Arsham’s Webpage. Retrieved from https://home.ubalt.edu/ntsbarsh/business-stat/otherapplets/comcount.htm

Zdenek, S. (2014). “More than Mere Transcription: Closed Captioning as an Artful Practice.” UX: User Experience, 14(1). Retrieved from http://uxpamagazine.org/more-than-mere-transcription/