Presenters

Kris Purzycki, UW-Milwaukee

Peter Brooks, UW-Milwaukee

Review

Digital games and Old Dominion University were underlying themes of my #cwcon16 experience. This resulted in attending panel E1, “Approaches to Teaching Cultivated Community Spaces Surrounding Games,” which included two presentations, one by Kris Purzycki (an ODU graduate) and the other by Peter Brooks, both from UW-Milwaukee. Purzycki intended to present with a partner, but his co-presenter was attending his own graduation that day and could be in only one place at a time.

I drove from Richmond, Virginia, to Rochester for C&W with two ODU colleagues, both of whom engage in game scholarship. I had just finished a games studies pedagogy seminar with one of those colleagues, and the conversation inevitably shifted to games and gaming. One of the questions we raised at various times throughout the 8-hour trip was how to archive mobile game experiences without relying on emulation hardware and software. Of special interest became archiving games as played for study on native devices, meaning the need not only to archive digital versions of games, but also to collect and archive the various mobile devices on which the games were originally played and for which each version was originally designed or optimized. This became a galvanizing question for us: how do we archive not only the hardware and the software, but provide facilities to study the games as played on their original devices?

This background explains my attendance at this panel: during social interactions at a local establishment (read “over drinks at a bar near the conference hotel”) the night before, I learned Purzycki’s topic would be archiving digital game experiences. While the title of his presentation as submitted was “Teaching the Game Experience: An Ecological Approach to Genres of Paratext,” a visit to the Strong Museum of Play had revised the focus of the presentation to address the archiving of digital gaming experience.

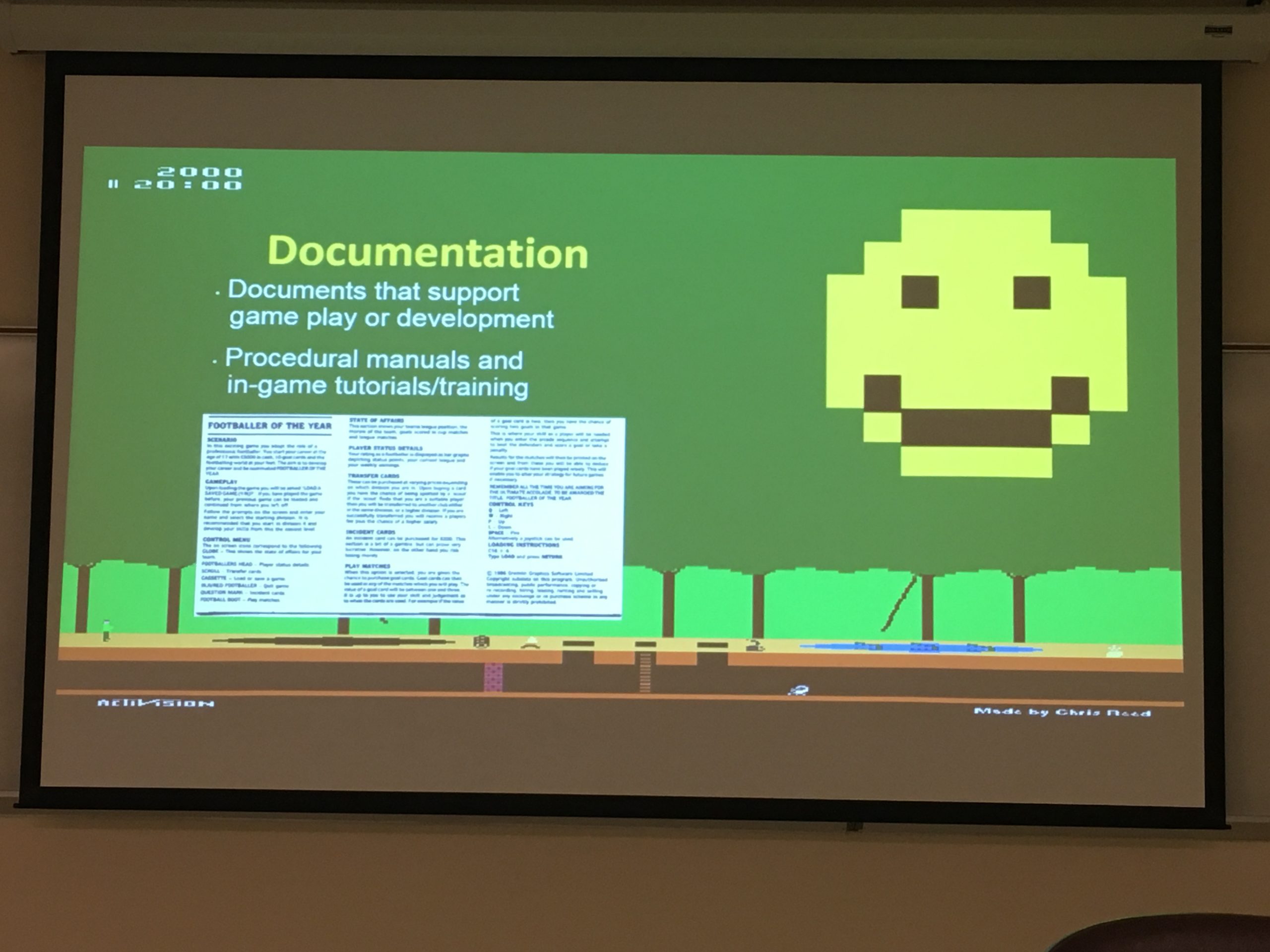

Purzycki provided an overview of current efforts to archive digital games, like those underway at the Strong Museum of Play. He described the challenges of archiving the variety of artifacts and genres that surround the gaming experience, genres that include hardware and software, of course, but also documentation, user manuals, gaming community communications, print and digital materials, marketing and packaging materials, versions, and the enigmatic, difficult-to-capture gaming experience. While efforts are being made to collect, archive, and catalog portions of the gaming experience — primarily focused on on what Decker, Egert, Phelps and McDonough (2012) term “significant properties” deemed significant by stakeholders — Purzycki identified two major obstacles to developing strategies and techniques to archive the gaming experience itself:

- A lack of prioritization (in terms of time and resources) of the task of capturing the gaming experience.

- The complexity of computer games compared to other digital artifacts, including platform dependency, unique game- and platform-specific peripherals, and confidential and proprietary hardware specifications.

Purzycki proposed the genre ecology model (Spinuzzi and Zachry, 2000) as a potential method for identifying and archiving the deeply interrelated artifacts and experiences bound up in digital gaming. He posited that an ecological approach to archiving better incorporates players and player communities in the archive by articulating an open-ended, dynamic ecology of resources across multiple domains and genres as the target of a digital gaming archiving project. The genre ecology models offers a framework for identifying, collecting, and recording both textual and paratextual artifacts from developer and player communities in addition to the layers of player experiences related to various hardware platforms, software releases, and physical consoles.

In the second presentation, Peter Brooks remained focused on the experience of game play but shifted from archiving the experience to reflecting on the experience of game play as a teaching technique. In the presentation, titled “Pressing the Pause Button: Metacognitive Moments in Classroom Simulations,” Brooks cited Zagal’s (2010) ludoliteracy as a for students to recognize opportunities to “game the game” (Consalvo, 2007), to experience and learn from simulated experiences (like time-pressured decision making or ethical dilemma scenarios) that can’t easily be easily built in a traditional learning environment. Brooks focused specifically on teaching and learning meta-awareness of experiences in the classroom by reflecting on the results of classroom simulations. The goal of such meta-awareness, according to Brooks, is to transfer the critical skills, knowledge, and experiences of ludoliteracy in other courses, professional contexts, and areas of learning and development.

Both Purzycki and Brooks presented a critical approach to games and simulations that is a welcome respite from sometimes ubiquitous calls to gamify the curriculum. Rather than approaching games as instrumental pedagogical tools, both presenters named and presented games as complex cultural artifacts and experiences that require critical approaches for understanding and learning from them. The growing field of game studies is richer for the critical approaches Purzycki and Brooks applied, an approach that seeks to understand, use, and record what it means to play a digital game.