Title: Pokémon Go

Publication/Creator: Niantic

Publication date: Released July 6, 2016

Experience here/Website: http://www.pokemongo.com/

Pokémon has been a cultural icon for many years now. Originated as a Gameboy game, this Japanese media franchise that includes several games and films, an animated TV show, and a trading card game. Most recently is the mobile augmented reality game Pokémon Go that was released in July of this year. Part of the glory of Pokémon is that it draws an audience from a variety of backgrounds and interests because of how large the franchise is, but the recent mobile game also finds itself attracting various types of gamers–particularly those who grew up with the Pokemon franchise in the middle to late 1990s. In this blog entry, we consider how the collaborative aspects of the game attracted users. We begin with a “cliff notes” style explanation of the game and its initial appeals for users. We conclude by questioning the staying power of the game in light of the recent downturn in active users, and encouraging conversation about the future of augmented reality games and interactive applications like this one.

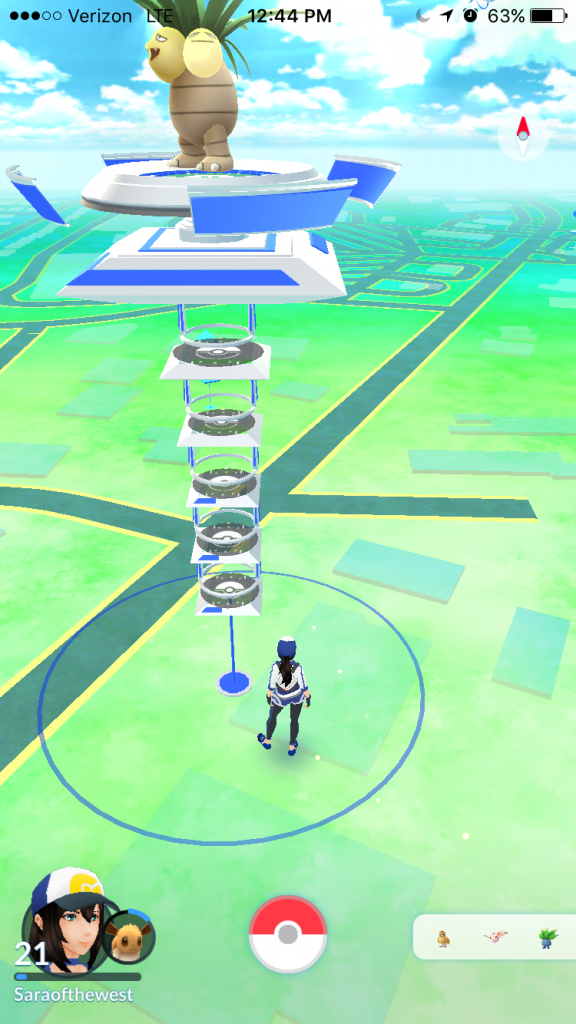

Pokémon Go is a free, mobile game that uses augmented reality and GPS to locate, catch, and battle Pokémon creatures. Players can gain experience (XP) by catching Pokémon, picking up items at Pokéstops, battling at gyms, and by evolving Pokémon. Pokéstops are places, such as coffee shops, parks, historical markers, and churches, that players can visit in real life, but in the game they are used to collect Pokéballs to help catch Pokémon or potions to help heal injured Pokémon from battling. Players can also use lures at Pokéstops that will attract Pokémon, and thus often other players, to that location for a 30-minute time period. (Although outside of the scope of this review, we would like to note there has been some controversy around the appropriateness of playing Pokémon Go in particular locations, like the Holocaust Museum, as well as concerns about access as some minority communities, and rural communities, have significantly fewer Pokéstops and gyms that urban white communities.)

Like Pokéstops, gyms are designated locations where players can go to battle for XP and ownership of the gym. An important part of gym battles is the team the player chose earlier in the game. There are three team options that players can choose from: Valor, Mystic, and Instinct. If the gym is currently owned by the player’s team, the player can battle the gym to raise its prestige and make it more challenging for an opposing team to take over. Alternatively, if an opposing team has ownership of the gym, the player can battle the gym to reduce its prestige and, eventually, take ownership.

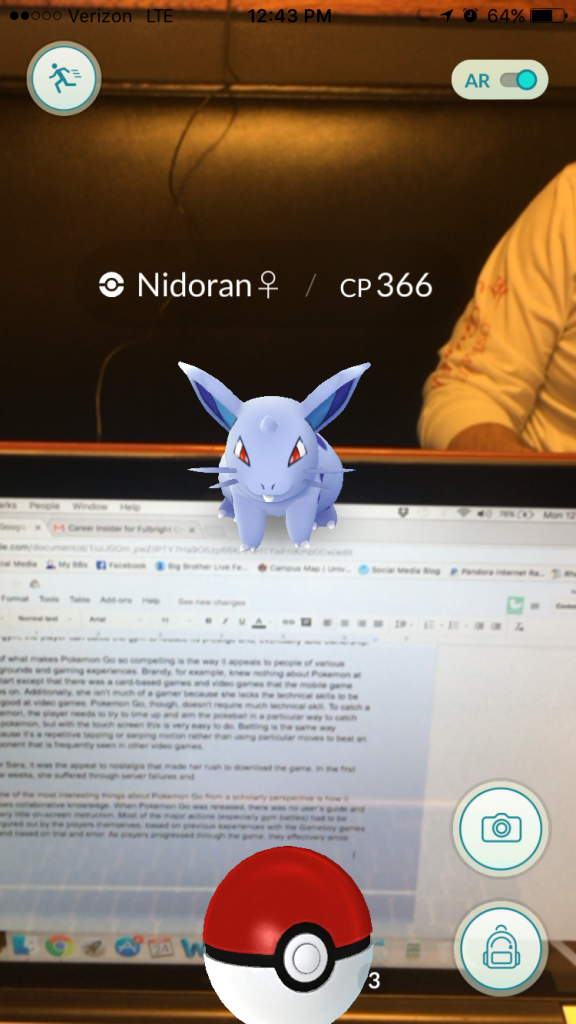

Part of what makes Pokémon Go so compelling is the way it appeals to people of various backgrounds and gaming experiences. Brandy, for example, knew nothing about Pokémon at the start except that there were card-based games and video games from which the mobile game draws. Additionally, she isn’t much of a gamer because she lacks the technical skills to be any good at video games. Pokémon Go, though, doesn’t require much technical skill. To catch a Pokémon, the player needs to try to time up and aim the Pokéball in a particular way to catch the Pokémon, but with the touch screen this is very easy to do. Battling is the same way because it’s a repetitive tapping or swiping motion rather than using particular moves to beat an opponent that is frequently seen in other video games.

One of the most interesting things about Pokémon Go from a scholarly perspective is how it uses collaborative knowledge. When Pokémon Go was released, there was no user guide and very little on-screen instruction. Most of the major actions (especially gym battles) had to be figured out by the players themselves, based on previous experiences with the Gameboy games and based on trial and error. As players progressed through the game, they effectively wrote their own instruction manuals and shared them with others. This heavily points back to Henry Jenkins’ discussion of “participatory cultures” and the fan-based cultures that form around them. In this case, the fans of the games created manuals, Wikis, and even third-party applications to help other players.

In addition to this sharing, the game itself, especially in its early days, spurred collaboration among users in the physical space. In the first few weeks after the game’s release, Sara, a long-time Pokémon gamer, remembers playing while staying in a beach town outside of Los Angeles. Every night, other players would set up lures at Pokéstops along the pier, and every night, more than 100 people would mill around the pier area, catching Pokémon. Players would point out locations to other people, talk about what they’d caught that day and what they still lacked, chat about what team they were on, and razz other people who weren’t on the same team. While there were probably few players making long-lasting friendships and connections, the players formed a sort of shared discourse community around the game. The knowledge created in the virtual space was transferred and maintained in both the physical and virtual spaces.

Pokémon Go’s interactive and collaborative elements were an early drawing point of the game. However, the game, which at one time had more installs than Tinder and more daily active users than Twitter, seems to be losing popularity. By mid-August, the game lost already lost about 15 million of its daily active users and a great deal of engagement, and has even garnered the nickname Pokémon Gone.

To attempt to account for the application’s decline, we note that many of the game’s interactive aspects fail to be sustainable in the long-term. We identify four main reasons for the decline in interest, from our experiences and from what we have heard from other players:

- As users level up past Level 20, the amount of XP needed to level up becomes almost insurmountable. However, as users level up, the level of the Pokémon they encounter also goes up, making it more difficult to catch Pokémon and thus get the amount of XP needed to get to the next level of the game. In addition, as users level up, the need for collaboration with others is needed less often. For example, gyms have gotten to levels so high that they can rarely be taken over by a group of people.

- The application no longer uses the “step feature” which at one time told users how close or far they were from a particular Pokémon. Without that feature, users have to wander aimlessly and hope that the Pokémon they want will appear on their screens. Going along with this, the same Pokémon continue to spawn so it no longer has the excitement of discovering a new Pokémon because, although many players haven’t “caught them all,” there’s no telling where or how to do so within the player’s means. This makes efforts like the previously mentioned group interaction at the pier almost unnecessary: lures are used less frequently since they attract the same Pokémon, and no one needs to be told that there’s another Pidgey nearby. (A Pidgey is a common Pokémon to appear.)

- There have been no new Pokémon added. In the beginning, part of the joy of the game was encountering a Pokémon a player had not seen before. This rarely happens as players get much later in the game. As soon as second generation Pokémon are added to the game, it seems likely that there will be a spike in daily active users again, but that excitement will likely fade over time as well. Because users know that other generations of Pokémon exist and will undoubtedly be added to the game, they resist evolving their Pokémon because they want to wait until that Pokémon has the option of other forms.

- The game doesn’t point back to the Gameboy games enough to maintain the original appeal to nostalgia. For example, in the Gameboy games, Pokémon could be leveled up by battling, and the type of Pokémon used in the battle played a more significant role in the outcome of the battle. But more than that, a large part of the Gameboy games is battling other trainers — an element that, despite the early focus on interaction, has not been incorporated in the Pokémon Go application.

Pokémon Go is richly interesting in that it uses collaborative knowledge-making in virtual spaces and translates that to the physical space as well. But because collaboration is no longer as necessary, the game has lost much of its appeal, even for experienced Pokémon gamers. In-game events, like the Pokémon Go Halloween celebration, will likely spur some activity, but we don’t know how often these events will occur. A recently launched wearable device also allows users to log time in the game a lot like one would use a Fitbit (worth noting, however, is that with this device, players need not even open the game to catch wild Pokémon that they’ve already encountered).

Niantic still supports the game and is still rolling out updates, but what does Pokemon Go’s short history tell us about the future of similar applications? Though we cannot comment on the future of Pokémon Go, other applications will no doubt seek to capitalize on elements of its early success. What would Pokémon Go, or related games, need to do to have a sustainable gameplay experience? Is augmented reality still a desirable game element? Should virtual applications resist making interaction in the physical space a main component? Businesses with Pokéstops and Gyms nearby have used Pokémon Go to attract customers, but how might games like Pokémon Go be incorporated into the classroom (see, perhaps, the collaborative Pokemon Go Syllabus)? Let us know what you think in the comments!