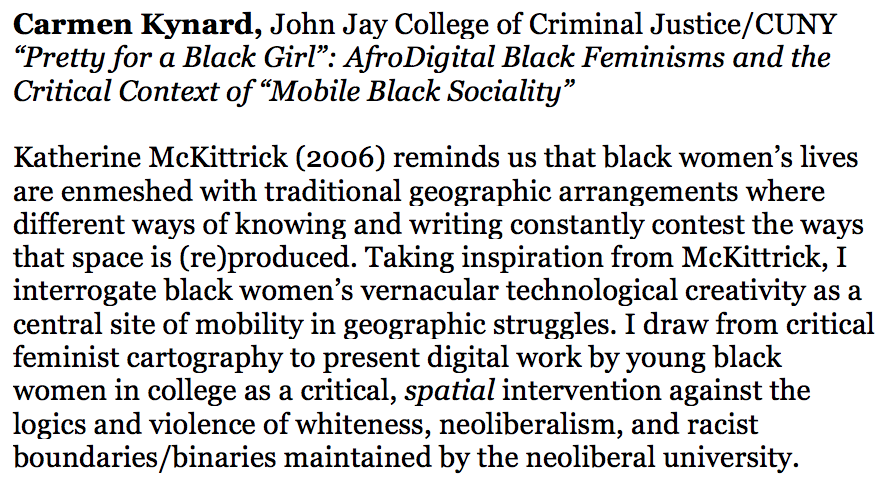

Carmen Kynard, Associate Professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, gave her fabulous keynote, “‘Pretty for a Black Girl’: AfroDigital Black Feminisms and the Critical Context of ‘Mobile Black Sociality,’” at the Thomas R. Watson conference at the University of Louisville on Thursday morning, October 20th.

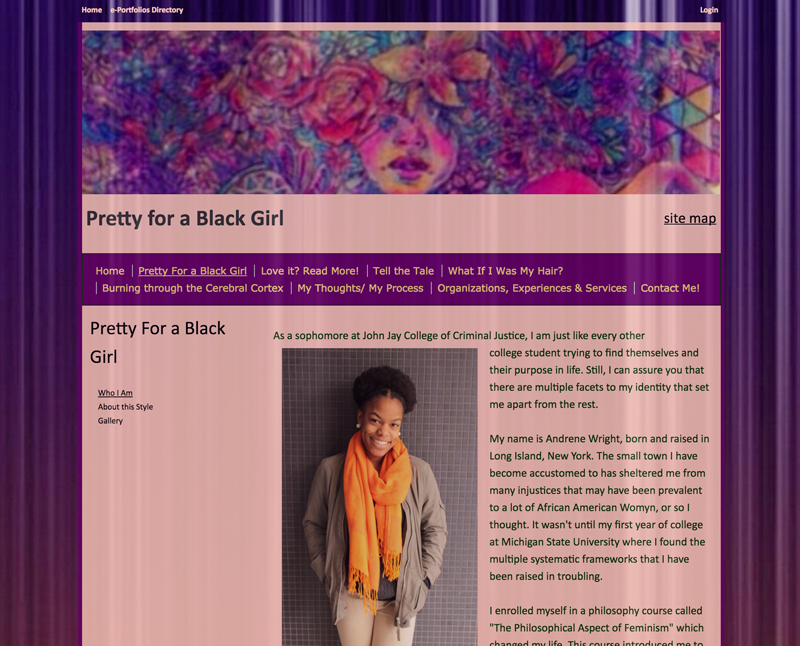

Kynard began her talk with a brief, but vivid summary of her article of the same name. The article centers on a young woman named Andrene who created “a dope website/ePortfolio” called “Pretty for a Black Girl” (pictured below). Andrene’s website uses space, color, sound, images, links, and language to critique the color caste system which values beauty based on its proximity to whiteness.

The article draws on the work of cultural geographer Katherine McKittrick’s (2006) and Fred Moten’s (2015) concept of “mobile black sociality,” to help readers see how Andrene’s website leverages “AfroDigital black vernacular” (ADBV) to critically and spatially intervene in the racism of the neoliberal university.

The article draws on the work of cultural geographer Katherine McKittrick’s (2006) and Fred Moten’s (2015) concept of “mobile black sociality,” to help readers see how Andrene’s website leverages “AfroDigital black vernacular” (ADBV) to critically and spatially intervene in the racism of the neoliberal university.

“Pretty for a Black Girl,” Kynard argues, enacts its “AfroDigital black feminisms” through not only African American morphosyntax, but what Kynard calls AfroDigital black vernacular: “a cultural-spatial contouring, multimedia blackscapes, and black navigational messaging as ethos.”

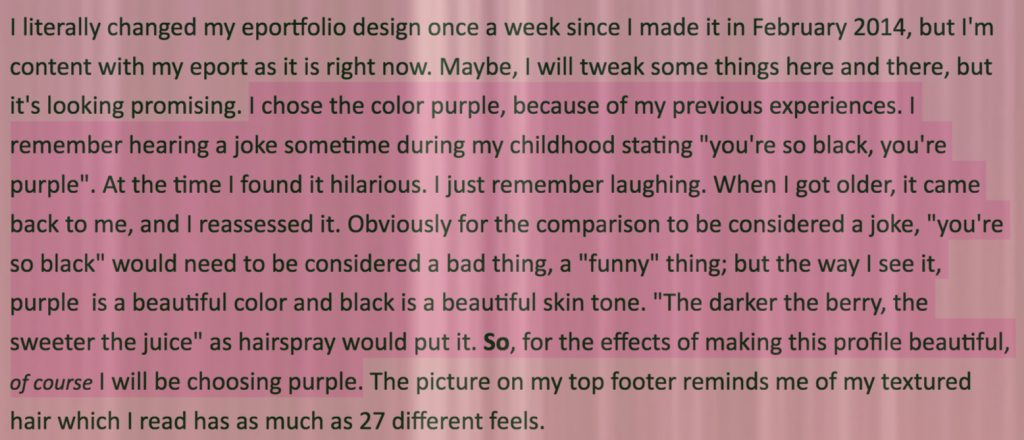

Kynard offers as an example Andrene’s use of a purple background as a meaningful rhetorical act. Andrene explains her choice:

Here, then, Andrene uses color–an extra-linguistic component of ADBV–to enact her AfroDigital black feminism, re-approrpriating purple as positive, rather than negative, symbol of black female beauty.

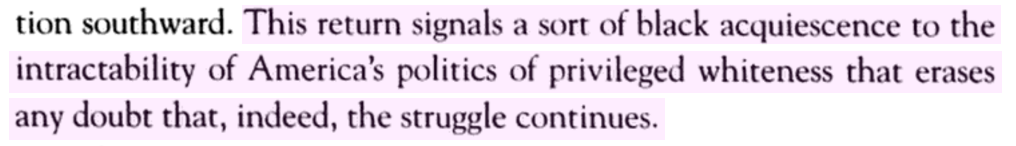

Kynard’s talk, though, extends this analysis out onto campus, an often hostile space for black women. Kynard begins with the story of an unknown faculty member who ripped into pieces one page of Anna Everett’s, “The Black Press in the Age of Digital Reproduction” left behind in a photocopier. One sentence was especially, and purposefully, torn to shreds:

This act of aggression prompted Kynard to ask:

“What is so threatening or offending about black digital spaces?”

Kynard goes on to tell a second story, this time about Andrene’s negotiations with white faculty, first as a research assistant and then as an intern, where her embodied literacies—as presented in “Pretty for a Black Girl”—were rejected as unsuitable for teaching other students about constructing ePortfolios. Reflecting on what it means for a white professor to tell a young, black woman that her embodied literacies are unprofessional or too provocative, Kynard then asked:

“What is so threatening or offending about the presence of black digital spaces whose political urgency dates back to post-slavery resistance? What is so alarming about it in college English classrooms?”

These are questions that deserve our attention as scholars, instructors, and media consumers/producers ourselves.

As instructors and scholars especially, it is important that we make room for AfroDigital black vernaculars (among others) in our conceptions of what counts as legitimate. Kynard, for example, recalled how in her workshops attendees often critique the extra-linguistic components of “Pretty for a Black Girl” as distracting from Andrene’s “real” writing. The extra-linguistic components of “Pretty for a Black Girl,” though, are real writing. Andrene simply eschews what Kynard calls the “Western fascination with words.”

Indeed, this kind of criticism of ADBV strikes me as not wholly unlike the faculty member who ripped up Kynard’s copier materials, the faculty member who told Andrene that her website was too unprofessional and provocative, and even the recent federal court of appeals decision that banning employees like Chastity Jones from wearing their hair in dreadlocks is not racial discrimination. In all of these cases—Kynard’s copier materials, Andrene’s embodied literacies, a black woman’s hair—black women are being told that they, themselves, are inappropriate.

As Kynard reminds us, though, recognizing and valuing AfroDigital black vernacular is no cure-all for the racist and neoliberal logics which delegitimize the embodied literacies of often-marginalized students; there is still much work to be done. As Kynard put it:

“The field in which we make meaning ain’t done even half the work it could and should to theorize what it means to design and mobilize as black women at this space and time.”

So, let’s get on it.

1 Comment

Thanks for this review, Maggie! It was a powerful talk!