Presenter

Eli Goldblatt

Review

In his Watson Conference keynote paper, Eli Goldblatt narrates the development of an ongoing partnership of literacy sponsors (including higher education, local nonprofits, city services, and a public school) in order to turn an abandoned block near a struggling (but improving) elementary school into an educational community space/urban garden. He discusses the mobility work of this network of literacy sponsors in their efforts to support the literacy of a disadvantaged urban population of students in northern Philadelphia, describing mobility as both a sign of health and of distress depending on the populations and their motivations for moving/mobilizing.

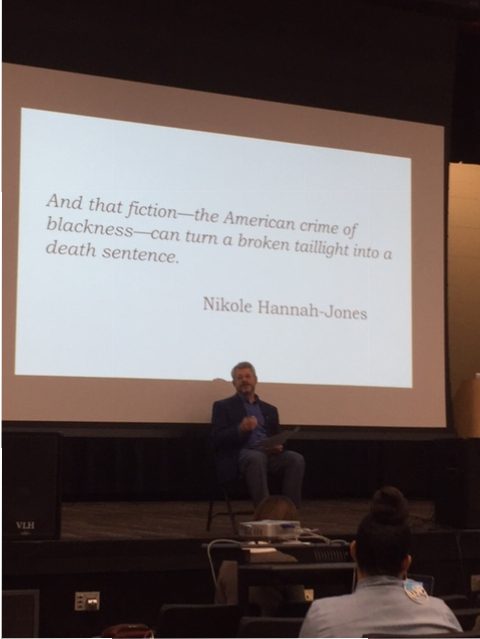

In this final keynote session, Eli Goldblatt offered up several ways for conference-goers to think about our roles in the complex relationship between race and literacy. Following typical Watson Conference procedure, rather than describing his keynote paper (which had been workshopped in the Watson Symposium in February 2016, and the final version of which all conference-goers had the chance to read prior to the conference), Goldblatt read what he called a “professional love letter” to Carmen Kynard in response to her rich feedback on his earlier draft at the Symposium. Addressing Kynard’s concerns about the absence of race in Goldblatt’s analysis of local networks of literacy sponsorship surrounding an urban educational multi-use community space, Goldblatt openly and honestly began his talk with questions he had recently received from the interim director of Tree House, the nonprofit literacy organization with which he has worked for several years. This new director, a white woman, asked him how race plays into literacy at Tree House. Goldblatt offered the question up to us: what do we as a field have to say to her? How does race form the context for literacy learning in America? He continued on to say that both the “fiction of race” and the “palpable reality of racism” can (and are) easily ignored by the dominant culture, which tends not to recognize the suffering of others. Drawing on his own personal stake in the violence of racism, Goldblatt told us of his son, a large multi-racial man who he could imagine pulled over and hurt by police. He reminded us that literacy is always local, which means that Tree House must ask: how does a white person act responsibly in a literacy institution sponsoring African-American learners? He told us that “people learn reading and writing within the fabric of their intimate and ongoing lives,” and pointed out how hard it is “to put local literacy into practice if you don’t feel it in your pedagogical bones and renew your commitment to social progress every day.”

Following Goldblatt’s speech, moderator Anis Bawarshi asked the audience members to write and reflect for 5 minutes, after which the floor was opened up to questions. The following conversation included a range of questions and comments, such as: What can mobility studies do to make visible the effects of racism? How do we stay in dialogue with people like the interim director of Tree House, but not lose African Americans as our audience; indeed, how do we recognize that they are an audience with authority who needs to be conceptualized in our dialogues? How do we create more opportunities to honestly and safely discuss issues of race and racism that are relevant to our campus communities? Perhaps we need to look at the laws that are supposed to protect us from racism, and perhaps mobility means looking back at the historical context of laws meant to protect lives.

The panel ended with some final thoughts from Goldblatt on the unintended segregation that our fields of expertise tend to promote (segregation based on our own specialized knowledge) and the subsequent need to seek out interdisciplinary connections surrounding larger issues such as race.