Presenters

Bridget Gelms, Miami University

Dustin Edwards, University of Central Florida

Rich Shivener, University of Cincinnati

Review

In “Life of the Networked Body: Harassment, Circulation, and Affect in Digital-Material Spaces,” the panelists each examined communication in digital spaces by focusing on the role of the body and its various identities, positions, and patterns of movement.

The first speaker, Bridget Gelms, presented her research on the online harassment of women in her talk “Digital Writing and Vulnerable Identities.” Given that women are more likely to be the targets of online harassment—especially women who engage in topics related to social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses—what are the communicative and emotional effects of managing these repeated attacks?

Gelms sought to answer this question by sharing findings both from interviews she conducted as well as from public and well-known accounts of women who have faced harassment via Twitter, such as Amelia Bonow the creator of the hashtag #shoutyourabortion. Gelms’ research revealed that online harassment isn’t just a one time event but instead is part of the everyday emotional and psychological labor women experience when using social media platforms like Twitter. For women, expressing oneself on Twitter is a double-edged sword where one must choose between silencing/hiding one’s voice or facing routine, misogynistic harassment in order to be visible. Gelms’ interviews also revealed that one’s visibility on Twitter and the harassment they* encounter are directly correlated: the more one uses hashtags, receives shares, or earns followers, the more frequent the harassment they receive.

As Gelmes reminded us throughout, certain bodies—particularly women’s bodies—will be more prone to violence on social media platforms. As instructors who may design assignments around social media participation, it is part of our responsibility to ask ourselves what risks there may be in requiring such public forms of communication and to reflect on the role gender has in relation to such risks.

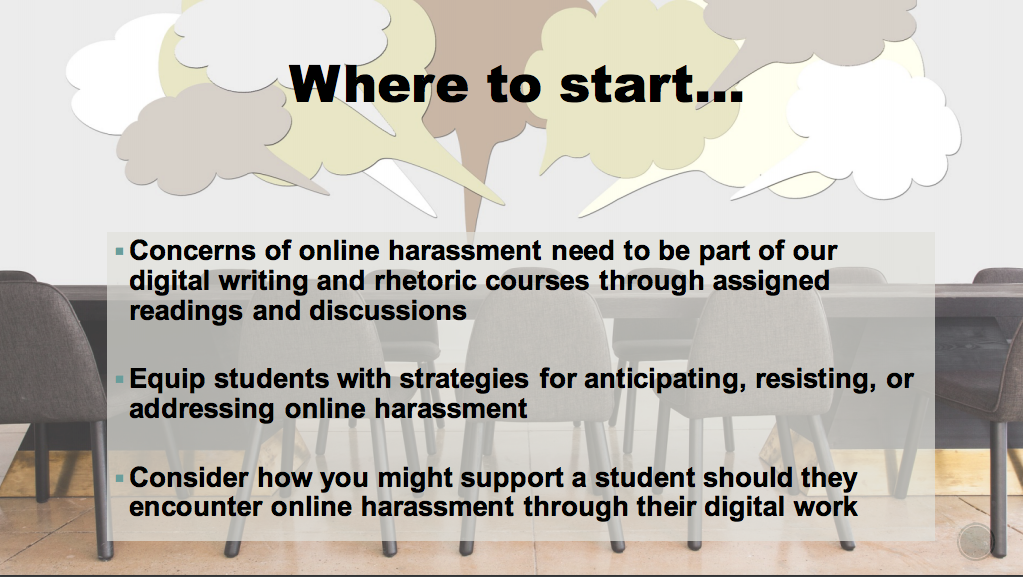

Gelms closed her talk with some suggestions and recommendation for how harassment as a topic may be brought into the digital rhetoric classroom:

The second panelist, Dustin Edwards, explored the concept of circulation by specifically attending to fitness tools designed to track and archive the movement of a body. Edwards began by narrating his own visit to the YMCA, which he described as moving with a “circulatory intensity”: in addition to the bodily movement of people using weights, treadmills, and other gym equipment, there is also the circulation of data as people make use of their phones and fitness technologies to track the intensity and length of their exercise.

Edwards called for attending to the deep circulation of this data, or the “multiplicity of flows that impinge upon and are produced through acts of embodied composing.” Deep circulation within the context of the YMCA means not only examining the circulation taking place at the physical location of the gym, but also how that data moves across various applications, networks, and systems as it is repeatedly stored and transferred. Such a perspective of circulation is important—perhaps even necessary—within the context of digital rhetorics given how personal data and communication is not just contained by the static design or arrangement of an application or platform; rather, data moves into streams collected by various third parties and institutions.

Edwards ended his talk urging us as rhetoricians not to fear deep circulation, but rather to generate new ethical stances from which we may understand and act given such flows.

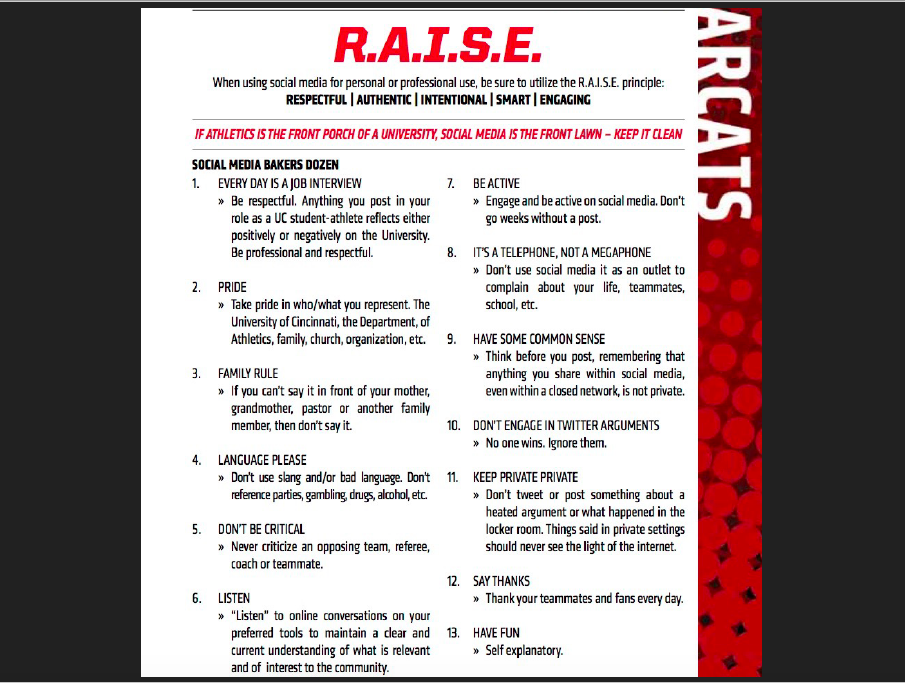

In the final presentation, “Intensifying Affective Ambience” Rich Shivener called attention to the numerous restrictions universities place on the social media accounts of student athletes. The intensity of restrictions student athletes face revealed that institutional power is not only exercised in context of their bodily labor (through playing, practicing, and dieting in aim of furthering athletic performance) but that it also takes place through their digital—and thus social, political, and personal—lives.

Such rules, as Shivener describes, places students athletes in a tough position where they are encouraged to “be active” and to “listen” but are also told they shouldn’t “engage in twitter arguments” or “be critical” within their social media spaces. Given the numerous rules, the social media accounts of student athletes become an extension of the university, where the values of an institution take priority over an individual’s right to free speech. Such circumstances become particularly uncomfortable for social media users since, as Shivener describes, even if you are unable to post about political issues, you are still exposed to their “affective ambiance”—that is, the “hum” of those stories circulating while you are participating in those spaces.

Such rules, as Shivener describes, places students athletes in a tough position where they are encouraged to “be active” and to “listen” but are also told they shouldn’t “engage in twitter arguments” or “be critical” within their social media spaces. Given the numerous rules, the social media accounts of student athletes become an extension of the university, where the values of an institution take priority over an individual’s right to free speech. Such circumstances become particularly uncomfortable for social media users since, as Shivener describes, even if you are unable to post about political issues, you are still exposed to their “affective ambiance”—that is, the “hum” of those stories circulating while you are participating in those spaces.

The Q&A portion of the panel brought about many questions and engaging discussions focused on thinking-through how this research may be brought into our writing classrooms and what further research needs to be completed in relation to bodies and digitality.

During the Q&A, Gelms was asked about how we, as instructors, may engage in conversations about harassment while still respecting the lived experiences of our students who may have had triggering experiences with harassment themselves. Gelms suggested that one strategy is to give students time to know what the upcoming lesson will be and to offer an alternative assignment as an option.

The Q&A also moved to discussions about what difference there is, if any, about what is taking place in our digital spaces versus how we interact in real world spaces when it comes to silencing student athletes. Shivener described how gestures, such as Kaepernick’s kneel during the national anthem, are also forms of restricting the voices of athletes who are assigned to represent a larger institution.

*Within this review, I have chosen to use “they” as a singular pronoun.