This month, we’re featuring another podcast as our webtext of the month. You might remember our post on Serial a couple of years back, and it seems only fitting that we tackle another wildly popular podcast from the same producers. In this post, I’ll be looking at the multimodal nature of S-Town, very similar to that of Serial. But while Serial’s website single-handedly introduced all the facets of the podcast (including court documents, maps, transcripts, etc.), S-Town’s story has been told not only across media but across different media outlets as well. In this text, I first introduce S-Town and situate myself as author of this piece. Then I discuss S-Town’s particular multimodality, and I also consider how it brings about some discomfort for fans of the series. Finally, I draw some implications for teachers of digital rhetoric, podcasting specifically.

Before moving forward, I’d like to note that this discussion will not be spoiler-free. But I believe even if you haven’t heard S-Town before and learn of some spoilers here, you will still enjoy it. There’s no way that the thoughts I’ll share could fully encompass everything that the podcast covers, and I’d still recommend that you listen.

S-Town, a Brief Introduction

S-Town, hosted by This American Life’s Brian Reed, tells the true story of John B. McLemore and his views of his small town, Woodstock, Alabama. McLemore first contacts Reed to ask him to investigate a murder in the town—a murder that he believes is being covered up by a particularly powerful, and wealthy, family. The twist of the show happens early: we learn that the podcast is not about a covered-up murder, but instead about McLemore himself. At the end of the second episode (referred to as “Chapters” in the podcast), Reed finds out that McLemore has died by suicide, and the rest of the podcast focuses on the falling out after his death, and explores questions about McLemore’s life, his potential fortune, and his sexuality.

Situating the Author (Me!)

As a small-town Southerner, I have a lot of feelings about S-Town far more than need to be shared here. I have some issues with how the story is told and the portrayals of the characters. I have questions about to what extent the portrait of S-Town’s inhabitants is true and not just a product of editing done by producers for viewers who have been conditioned to view small, Southern towns in a certain way. But like most listeners, I devoured the seven, hour-long episodes in just a few days. Both the story’s ongoing mystery and my frustration drove me onward.

I knew going into this project that I wanted to explore how S-Town’s story was told across multiple media and platforms. This type of composition intrigued me. I found that as I listened to the story, I visited other websites and platforms to find out more than just what was being told on the podcast. In a way, S-Town made me feel like an investigative journalist. But I also knew that these multimodal elements, though interesting, were not what drew me into the podcast in the first place. And I knew that part of the reason I sought out different media and platforms was that I wasn’t sure I was getting the whole story from just one medium. Thus, I don’t want to avoid my situatedness as author or to ignore some of the major issues.

S-Town has sparked a lot of conversation about voyeurism, exploitation, the privacy of suicide, the portrayal of small towns (Woodstock specifically), and the dismissal of small-town racism. Though the bulk of this text deals with multimodality, I welcome discussions of these topics and would love to hear thoughts from others as well.

S-Town & Multimodality in Podcasting

S-Town isn’t the first podcast to include multimodal elements. In fact, our webtext of the month on Serial discusses this very idea. In that text, Lindsay Harding argues that we should not just view Serial as a 12-episode podcast, but that we should consider those episodes as just part of the whole, including the many texts housed on the podcast’s website such as blogs, court documents, and maps, to name a few.

S-Town is a bit different in that the website itself does not contain all the information to make a cohesive whole; perhaps because of this lack, other media outlets have stepped in to provide more information in a variety of forms. Most notably, photos have become a huge part of S-Town’s story, combining with audio to provide a more multidimensional view of the people and places of the podcast.

S-Town co-producer Julie Snyder noted that while Serial was more like a television series, S-Town is “more like a novel.” S-Town’s official website plays with this idea, introducing each episode of the podcast as a “chapter” with a pull-quote (shown below). But where Serial’s website featured a lengthy drop-down menu of secondary texts, S-Town’s website lists only the episodes and podcast credits. Even the “About” section features little information.

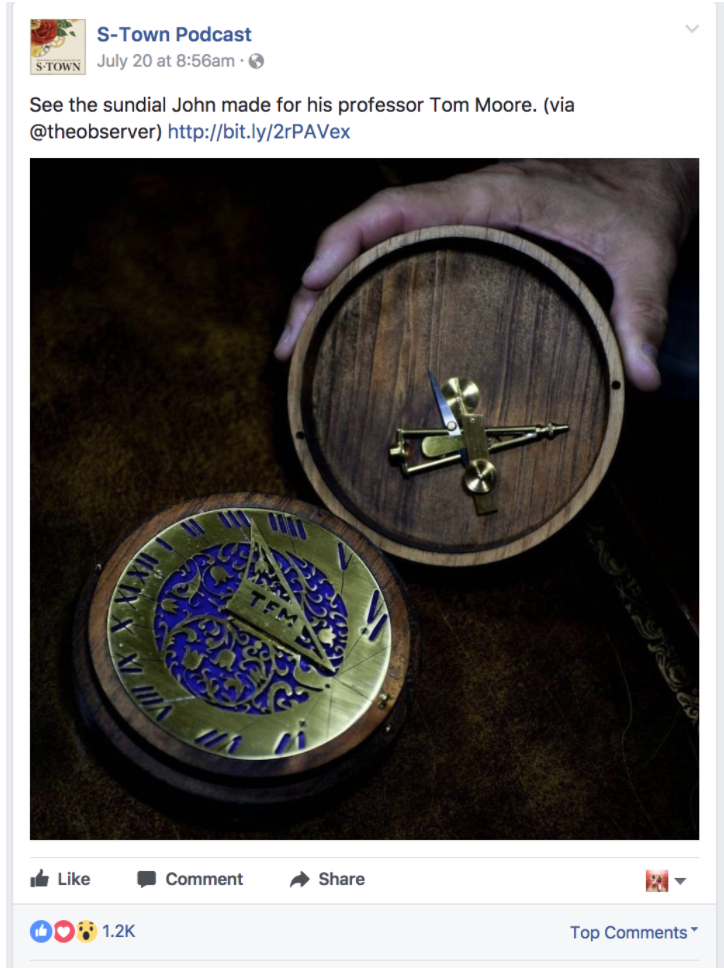

Navigating to S-Town’s social media pages, however, shows that the story is not contained only within the 7 episodes of the podcast. S-Town’s Facebook books features a variety of articles, sometimes linking to other outlets who have done their own research about McLemore and Woodstock, sometimes linking to interviews with Reed or other producers. It also features photos of artefacts mentioned in the podcast, such as the intricate sundial that McLemore made for one of his professors. Similarly, S-Town’s Twitter also directs followers to other sources to learn more about the people and places discussed in the podcast.

So while S-Town does not compile all the different modes of storytelling in one space, it does acknowledge the ways that the story is being told on different media and through different outlets. As other outlets compile media related to the podcast, S-Town uses some of its own platforms to link to that material, providing a multifaceted story to viewers but still allowing the separate news outlets their own authorship and investigation.

The Discomfort of Multimodality

In some ways just listening to the podcast makes me feel like I’m intruding into people’s lives. There are several points throughout the series that people–I almost wrote “characters,” but part of the discomfort here is that they are not merely characters–share things with Reed that they have not openly shared in other places. Though I know that the producers have ensured that full consent has been obtained, it still feels like I’m listening in on conversations without consent. As a casual listener, these people have no reason to entrust me with their secrets, but sometimes it feels that way nonetheless.

But, perhaps thankfully, there is still some separation between listening to these conversations and knowing these people. I could not just pick out these people based on their voices. But as S-Town has soared in popularity, photos have emerged of more than just inanimate artifacts. There are photos of those involved, both living and deceased. And while this undoubtedly speaks to the multimodality of storytelling, it brings, for me, a discomfort that I can’t fully describe. But I’ll try.

Daily Mail correspondent Ben Ashford has created perhaps the best compilation of S-Town-related photos (because of some of the issues noted above, I will not reproduce any photos within the body of this text). This compilation has become so notable that while discussing this article with other DRC Fellows, we all mistakenly assumed the photos were housed on S-Town’s own website. But this was not the case, and perhaps that is because of some of the reasons I’ve already mentioned.

Viewing these photos is even more of an uncomfortable experience. Some photos, like those of McLemore’s infamous hedge maze, seem harmless. They allow me to better understand Reed’s descriptions of the maze in the podcast, and McLemore’s frustration with the long process of growing the hedges high enough. Other photos, though, make me feel like I’m flipping uninvited through a family photo album. Many photos have notes that they were provided by people involved with the podcast, so it’s not as if the photos are being published without permission. But they still make me feel as if I’m viewing something I shouldn’t be.

I can’t dispute the fact that seeing the photos, in connection with the audio, provides a richly multimodal experience. And sometimes discomfort is okay, sometimes it’s necessary to move people from mere observation to the realization that, in this case, people are people, not characters. But though I’ve listened and I’ve done outside research, though I’ve viewed the photos and read the interviews, I’m still not sure that I want that experience.

Implications for Digital Rhetoric & Teaching

Next semester, I’ll be teaching a course that asks students to create multimodal compositions, and one of those compositions is a podcast. Though I’ve taught multimodal compositions before, this is my first venture into podcasting. My experiences as a podcast listener, especially some of the discomfort I’ve mentioned above, make this a more daunting experience than I thought it would be.

The multimodality of S-Town is intriguing, and it does show how a story can be told in many forms, through many platforms. I’d like my students to consider this: that just like any composition, a podcast does not exist in an isolated context. But I can also see how discussions of consent and ethics are absolutely necessary for this kind of work (and, of course, any kind of work). If we wish to teach our students how to compose in multiple spaces, we must also consider the ethical obligations for ourselves as instructors and for our students as creators. I think that even asking students to talk through the discomfort of S-Town or similar podcasts might create avenues for discussions of the moral, ethical, and legal obligations of creators.

In addition, it’s important to note that podcasts like Serial and S-Town have changed the way podcasts are viewed in popular culture. Bronwyn Williams (2014) notes that while instructors often find value in teaching multimodal genres, such as the video or the podcast in general, they sometimes fail to consider how popular culture influences students’ perceptions of these genres. Podcasts are not generally stories told over the span of several episodes. Instead, they usually tackle a single topic within a general idea from episode to episode. But it’s important to acknowledge, especially when teaching podcasts, that the podcasts which have been increasingly thrown into the public eye have been a bit different. Serial and S-Town, for example, capitalize on the public’s true-crime obsession and the episodic nature of televised series. If students have only listened to one podcast, it may be one of these, and thus it is important not just to teach the podcast but to talk about the different moves within the genre–and how and why those moves are made.

As I mentioned, it would be impossible to discuss everything about S-Town in just a short blog post, but I welcome any conversations about the podcast or teaching with the podcast in the comment!

2 Comments

You make a great point about our perceptions of genre in the digital sphere, where so much of what we compose can be given to borrowing (or is it stealing?) from so many other peoples’ lives.

In regards to S-Town, I hope to touch on S-Town, Serial, and Making a Murderer while teaching Bryan Stephenson’s _Just Mercy_ in the Fall.

Stephenson’s book falls squarely in the nonfiction camp (along with the two podcasts and Netflix series mentioned above) , but could also be said to crossover into the genres of creative nonfiction and true crime with its subject matter (i.e., death row inmates ala Truman Capote in _In Cold Blood_), as well as its use of dialogue from decades ago. This dialogue is quoted as naturally as if it had taken place while the book was being written less than five years ago. Some of it could in fact be recorded, since the author is a lawyer and might have relied on interviews that were given on the record for source material, but most of it is told in the anecdotal he-said, she-said colloquial style reserved for recounting a personal experience or memoir.

The book also situates itself very nearly as a realistic adaptation of Harper Lee’s _To Kill A Mockingbird_, almost as if it were told to set TKM’s record straight on just how deep the rabbit hole goes as far as the U.S. judicial system and racial discrimination go. Very much like S-Town, especially with its expose of a corrupt Alabamian municipality (but no horologist, unfortunately), it frequently references and flirts with the southern literary tradition, invoking gothic tropes as old as the Civil War to call attention to some of the worst instances of injustice and oppression in United States history.

All of these appeals to genre conventions of popular culture (e.g., true crime), and particularly the Southern literary tradition, appear to positioned to reach the broadest possible audience while impressing upon those readers that justice reform and showing mercy toward our fellow human beings is necessary no matter how you look at the issue of capital punishment, or race, or the South. In other words, he uses his ability to blend genres and use multiple modes of discourse in order to argue the best case he possibly can, like any good lawyer.

As far as implications for S-Town and the issues you raise about multimodality, _Just Mercy_ seems to offer a complementary text for listeners to read after they listen to the story of John B. McLemore, especially if they’re interested in finding out how the show’s creators use the historical context of the South and southern literary genre conventions (i.e., the southern gothic) to really sell a story.

But to situate this author, all that’s coming from someone who wants to teach and research from a southern studies angle, so of course I want to use it to tell about the South!

Thanks again for the post and hope your student produce ALL the multimodal compositions!

All best,

Josh

Thanks for your comment, Josh! Your point about the continuance southern gothic tradition is good–that’s especially evident in S-Town’s theme song, which I love. 🙂 I haven’t heard about the book that you’ve mentioned, but now I want to read it. I’d love to hear about how it goes over in your class.