Presenters:

Erin Banks-Kirkham, LaSierra University

Felicia Chong and Josephine Walwema, Oakland University

Lauren Short, University of New Hampshire

Review:

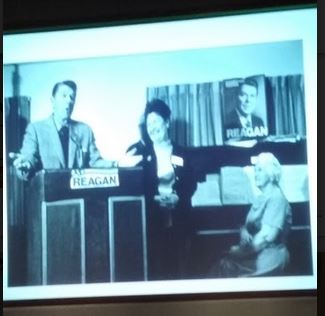

In the very first panel session of FemRhets, a trio of presentations explored the past and the present of U.S. political campaigns. Erin Banks-Kirkham presented first, and her panel “The Beginning of the Devolution: Women’s Representation Through Language in the 1980 Reagan Campaign for President” applied critical discourse analysis to archival material from the Reagan Presidential Library.

Focusing primarily on documents related to a “women’s issues” speech written for—but never delivered by—Ronald Reagan during his first campaign for president of the United States, Banks-Kirkham demonstrated the careful way the campaign worked to soften the candidate’s image as a “tough” Westerner by crafting a “caring” identity for the candidate.

Among the artifacts related to this campaign initiative, which was coordinated by the Women’s Policy Advisory Board, Banks-Kirkham located a memo titled “Glossary of Terminology Preferable to Modern Women”; its text, which includes some explanation about the use of Ms. as an appropriate honorific, was created as part of an effort “to help sensitize the campaign.” The first page of the memo drew a number of chuckles from those in the audience for its absurdity.

During the presentation, Banks-Kirkham credited Jackie Jones-Royster’s call for scholars to recover women’s work as a primary inspiration for the project. Later, in the Q&A, it was noted that the glossary’s contents include several defined terms that still seem to be necessary 37 years later.

Felicia Chong and Josephine Walwema, presenting “Political Advocacy: Women’s Anti-Feminist Rhetoric Against Hillary Clinton on Social Media,” were second on the panel schedule. Their recent work has focused on the dissemination—via social media—of writing by self-described feminists who targeted presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton during the 2016 campaign. The researchers provided a snapshot of their larger project. Chong stated that she and Walwema focused on social media in their study because “social media is the home of civil society.”

As an example of the of rhetorical work examined in their study, the pair spoke about about the edited collection False Choices: The Faux Feminism of Hillary Rodham Clinton (Versa Books, 2016). Critiquing this work and similar texts, Walwema and Chong emphasized the irony of anti-feminists using the term “faux feminism” as a way to denigrate the work and actions of others, and their presentation provided insight into the ways social media rhetorics shaped public perceptions of the first female major-party presidential candidate in the U.S.

In a closely-related presentation, Lauren Short described her case study on high-profile Christian-identified social media figures and their 2016 election rhetoric. Her presentation, “Stone Throwing in the 21st Century and Protestant Women’s Rhetoric in Response to the 2016 Presidential Election” briefly profiled influential bloggers who have massive online followings, such as Rachel Evans, and sought to understand the disconnect between -“protestant voices and voters.” Short demonstrated how such work is critically important given the “the ubiquity of the internet,” and since it allows scholarly insight into how conservative women publicly negotiate contentious issues related to right-leaning conservative positions that are distinctly anti-woman.

After sharing that twenty percent of registered voters in the United States are white Evangelicals, Short argued that popular Christian social media figures should not be written off as inconsequential “mommy bloggers”; rather, she continued, these women and their followers have a clear understanding that “life extends beyond the labor and delivery unit,” and should be taken seriously by scholars of feminisms and rhetorics. Unfortunately, Short concluded, many of the women she studied do not engage in social and political dialogue related to women’s issues.

Taken together, the presentations on this panel highlighted important and interesting work central to digital rhetorics. While Banks-Kirkham’s research is archival in nature and draws on artifacts that predate the digital public sphere, it highlights the importance of feminist research in historical archives.Tracing the historical arc of political party engagement with feminism—regardless of the party’s (or candidate’s) alignment or antagonism toward feminist movements—is important to enrich the work of scholars who delve into archival material from the digital age. Indeed, the archives Banks-Kirkham has been working with may never be digitized, so her work may be the primary means for documents such as the “Glossary of Terminology Preferable to Modern Women” to make their way into the digital spaces we spend so much time in.

Likewise when scholars such as Chong, Walwema, and Short dig deeply into more contemporary social media archives, their work sheds light on important cultural and political movements that otherwise might remain hidden from serious inquiry.