My dissertation research uses queer rhetoric as a lens for analyzing and studying moments of queering gender norms on Instagram. I took a case study approach and analyzed Instagram posts by Lady Gaga, Nicki Minaj, and their fans, and my ethical concerns about my research grew as I progressed through my writing and research. In particular, it became increasingly apparent that by the nature of studying photos posted to social media without directly contacting the original posters, I am imposing my own perspective and positionality with my readings of the photos. Furthermore, because I am doing a multimodal analysis, sharing photos is important for giving readers context to my analysis. However, in doing so, I am potentially risking the safety of anyone I share photos of and, at the same time, I am positioning people with complex lives and experiences as objects of study.

At the outset of my research, I was aware of the challenges and complexities that come with conducting online research (see McKee & Porter, 2009; Sullivan & Porter, 1997). However, my main concern initially lied with losing access to my dataset rather than having concerns for the well-being of those being studied. I was so focused on the data that I lost sight of the people and the very personal nature of studying gender performances. It wasn’t until I began to code all of my data that I began to feel some inklings of concern, and then this became heightened as I started my analysis. Through the research and writing process, I began to realize how my own positionality as a white cisgender woman would impact my readings of the data, and I relied heavily on Jean Bessette’s (2016) discussion of how situational readings of “queer” across time, space, and one’s own positionality are in order to ease my concerns over presenting my own reading.

In this way, I came to adopt more feminist research methods over the course of my writing and research as time and time again when writing the analysis I became aware of how my own reading might differ from someone else’s reading. An example of this can be seen in Figure 1 where the caption accompanying the photo is what led me to reading the photo as queering due to its overt expression of sexuality, which contrasts typical depictions and performances by women. However, when showing this photo and caption to a colleague (albeit not one who is particularly familiar with queer or feminist theory), my colleague did not read this photo as engaging in the queering of gender norms as proposed. As a result, I often spoke to my own positionality and couched my findings in my research by speaking to my own perspective, which is still useful given that it is a given different readers might read the same text differently but their viewpoints are still valid.

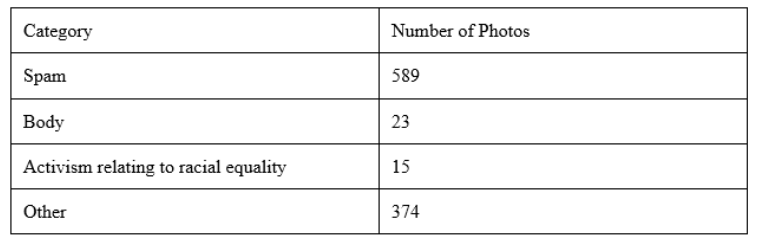

Another primary area where I adopted feminist research practices later in my dissertation research was related to including fan photos. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at my university did not require that I ask for consent to study fan photos, and my intent was to be a mere observer of fan interactions rather than to insert myself into the fan interactions through my own participation and through interviews. A sample of my coding of fan photos can be seen in Figure 2. (Note: The photos in the “other” category were largely posting photos in admiration of Nicki Minaj.) Some of the fan photos that used the hashtag #LadyGaga on Instagram also used other hashtags that would identify a person’s sexuality, such as #InstaGay or #lesbian. For fan photos that used the hashtag #NickiMinaj on Instagram, some photos used hashtags that spoke explicitly about the body and were sometimes posed in more provocative clothing or body positioning. Consequently, as I used some of these photos for my data analysis, I began to think about my own ethics as a feminist and queer theory scholar, and I grew more and more uncomfortable with the idea that I would be sharing photos of persons who had not given their consent. Most importantly, I would be sharing photos that could be in turn used for harmful purposes, such as outing an individual by sharing a photo that identified their sexuality or by enabling slut-shaming or other forms of policing women’s bodies, particular women of color.

As I was attempting to navigate these concerns, I sought the advice of other rhetoric and composition scholars, although not specifically digital rhetoric or feminist or queer theory scholars. Much of the advice I received drew on archival research for justification as folks suggested the likelihood of my research having an impact on people’s lives is so slim that there’s no need for concern. While I agree with those statements, given the nature of my research that is not a risk, no matter how unlikely, I am willing to take, and I have opted to edit the photos by blurring the faces to make the persons unidentifiable. (Furthermore, I am not including them here due to the ease of searchability of the website in contrast to the searchability of my dissertation, but for the sake of showing an example I am adding an edited photo of myself here. See Figure 3.)

From my experiences navigating ethical research practices as a part of my dissertation research, I argue that scholars need to adopt a critical and feminist framework for navigating the ethics of research. In my case, the steps involved in my own research led towards a path that would suggest I did not need to alter the photos: IRB did not view my research on social media as relating to human subjects, and advice other scholars suggested the chances of risk are so minimal they are negligible. However, as a feminist and as a person who tries to emphasize compassion and empathy, it is crucial that we as scholars think more deeply about our own personal ethics in addition to existing scholarship on the ethics of research, particularly digital research. In the end, we should feel good about the decisions we’ve made and provide justification for those decisions, especially when they may present alternative viewpoints than the dominant narratives.

References

Bessette, J. (2016). Queer rhetoric in situ. Rhetoric Review, 35(2), 148–164. http://doi.org/10.1080/07350198.2016.1142851

McKee, H. A., & Porter, J. E. (2009). The ethics of Internet research: A rhetorical, case-based process. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Sullivan, P., & Porter, J. E. (1997). Opening spaces: Writing technologies and critical research practices. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing.