Introducing Our Class: Digital Rhetoric in Health & Medicine

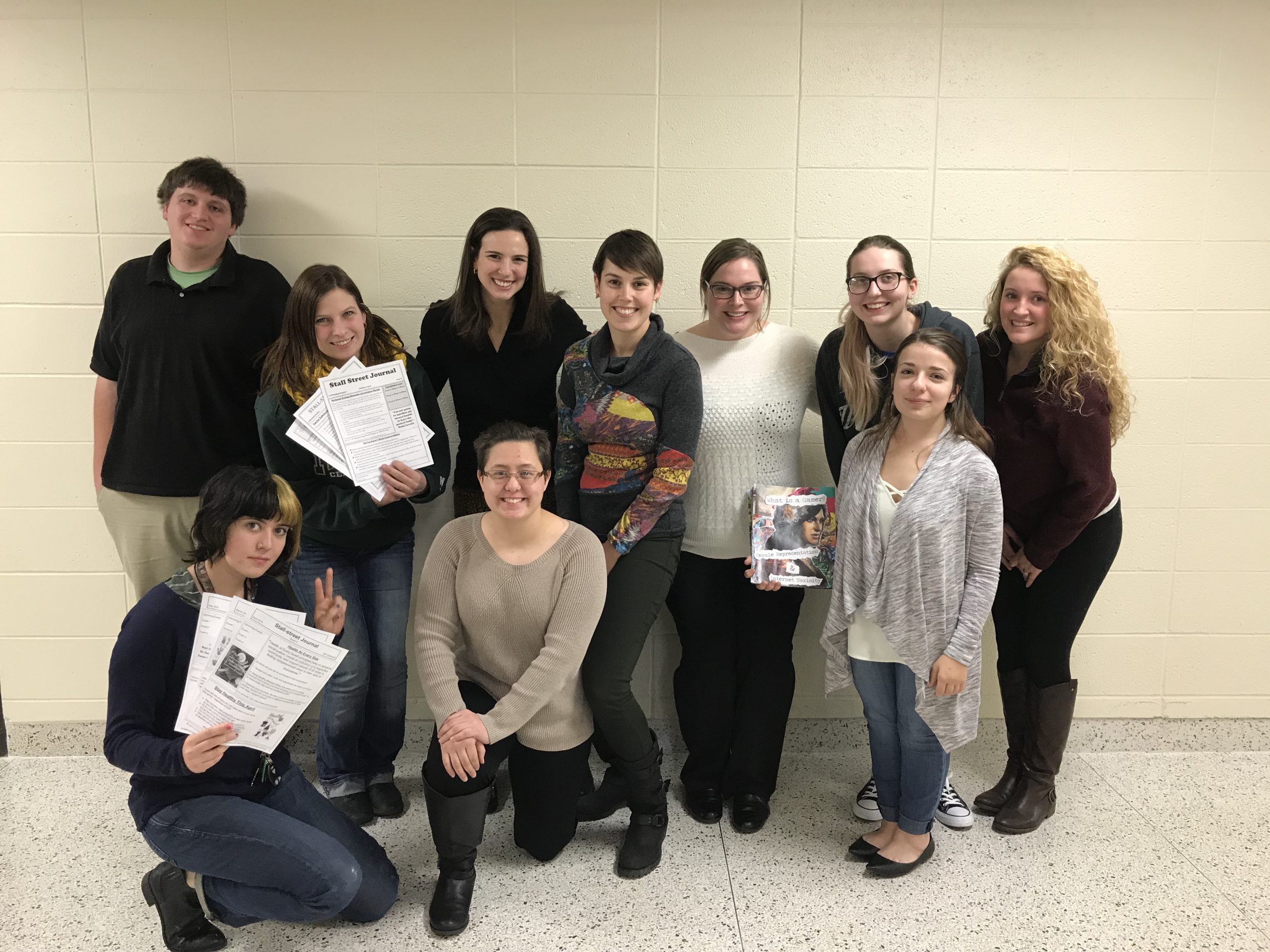

In the Fall of 2017, the nine of us met in an undergraduate course titled “Digital Rhetoric in Health & Medicine” at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh (UWO). For us students, all of whom are English majors, we found ourselves in many new and unfamiliar experiences. For instance, this was a new class, offered by a new English faculty member, and a course that focused on several unfamiliar fields of inquiry: digital rhetoric, surveillance studies, and wearable health technologies. All of these new experiences made it difficult to predict how such a course would connect to our English degree. As we engaged with the material and worked through our assignments, we found ourselves increasingly inquiring about these issues from the position of a rhetorical advocate – wanting to promote safer, more critical understandings of digital health technologies.

We felt compelled to write this blog post to overview the university and nation-wide exigencies informing the experiences in this class as well as its pedagogical structure, focused on fostering university partnerships. To do so, we highlight how these seemingly distinct fields of inquiry were woven together in our final projects. Our aim in this blog post is to illustrate how understanding digital rhetoric from an explicit surveillance studies perspective forced us to grapple with the questions: (1) what is data?; (2) who owns data?; and (3) how, as a digital rhetorician, do these questions about data impact and implicate my professional writing practices?

Tackling these questions in this course, we came to understand the user’s body as always being impacted by the design of digital infrastructures and the technical documents governing their use. Further, as we grappled with what it means to be a professional writer, we discussed with the ethical choices we, as technical communicators and designers, make in the composing of consent agreements between user and digital devices. Understanding then that we were implicated in these discussions as both user and designer/composer, when we began working on our final project (a collaboration with two campus health centers) we each felt personally compelled to design campaigns to increase the digital literacies practices of our peers as an example of local digital rhetoric advocacy.

Exigency for the Pedagogical Design of this Course

Three factors established local, and unexpectedly, national exigency for this course and its pedagogical design.

University Exigency: The Campus Budget & Access to Health Services

UWO is an institution situated within a state system that has, for several years, faced continual budget constraints. Such institutional finance constraints, we understand are not unique to UWO, nor the University of Wisconsin System at large. Across the U.S., we see other examples of higher education institutions similarly impacted by reduced budgets; there is an increased pressure to minimize free or reduced-cost services to students. Given these socioeconomic conditions, the decision to partner with the Women’s Center and the Student Health Center, which provide physical, emotional, and mental services for students, was intentional. Both centers are facing challenges to continue offering services to students in the midst of dwindling budgets. We hoped that our class partnership could further support their efforts to provide important resources and services to students on campus. We see institutional pressures to reduce access to student-focused health information and support as a social justice issue. This course, we believe, is a strategic pedagogical response to Natasha Jones’ call for scholars in professional writing to train students to become advocates and reject the temptation to “sit idly by in the midst of such sociopolitical and socioeconomic strain” (343). Our partnership with the two campus health centers allowed us the opportunity to structure our learning from “participatory approaches [which]engage empathy as a conduit to understanding and advocacy” (356). Coming to realize these real, ever persistent budgetary threats to higher education, this class underwent a reorientation from students wanting to learn to students wanting to enact change.

Departmental Exigency: The Case for Professional Writing in an English Department

Another local exigence informing the structure and purpose of this course was the reality this class was launched as a pilot course, aimed to attract students to a Professional Writing minor in development at UWO. Interested in demonstrating to students the breadth of career possibilities with a PW minor, Maria Novotny (our instructor and new Professional and Digital Writing hire to the English Department) designed a course that offered an expansive view of the interdisciplinarity of Professional Writing. We believe it is important to recognize the larger context informing this course, especially in relationship the increased emergence of Professional Writing programs within English departments. This course, attached to a new PW minor, acts as a response to the continued budgetary constraints implicating universities at large, and echoed above. Once again such a situation is not unique to UWO, as other departments across the country have taken up similar initiatives to create Professional Writing programs within their departments. We note this exigence then to acknowledge our own positionality in this course: we are upper-level English major students taking a Professional Writing course, which we have been advised, may increase our future job marketability.

National Exigency: Equifax, a Supreme Court Hearing, and #MeToo

Finally, a series of unexpected, contemporary events influenced the timeliness of our course. Specifically, as we began our fall 2017 semester, news broke of the Equifax data breach, which compromised millions of individual’s sensitive and personal information. The data breach, while unfortunate, was timely as it set an imperative for situating digital rhetoric along scholarship in surveillance studies. Later in the semester, the Supreme Court also held hearings on a digital privacy case in which police, without a warrant, developed a case against a robbery suspect by accessing their cell phone data. During this time, the #MeToo movement emerged and drew attention to how narratives of sexual harassment could be given voice and power through their circulation on digital infrastructures. All three of these unexpected occurrences served as further relevance for the need to consider the intersections of digital rhetoric, surveillance studies, and its impact on the body.

Background of Course

Inspiration for this course, which blended digital rhetoric, surveillance studies, and wearables, became apparent when Maria invited Les Hutchinson to speak to our class via Skype. Together, they shared how this course emerged as they began to collaborate around their research areas: Maria’s with fertility mobile apps and Les’s with digital surveillance. At the heart of these conversations was the shared need to establish more critical digital literacy practices in students who are frequent consumers of mobile apps and wearables, which capture personal data that is frequently inadequately secured. As such, Maria and Les spent the summer of 2017 co-creating what they call a “feminist surveillance as care pedagogy” (forthcoming in a Special Issue of Computers and Composition), which bridges together the intersections of digital rhetoric and wearables through the lens of surveillance studies.

With the course aimed to enact this “feminist surveillance as care pedagogy”, Maria shared with us on our first day of class that the purpose was to extend scholarly conversations around digital rhetoric to new scenes, focusing on the intersections of surveillance studies and wearables. Its intention was to demonstrate the scope to which digital rhetoric can and should be explored, particularly noting how new collections of bodily data (often through wearables) pose a risk to individuals and their private information.

To make these connections, the course was purposefully scaffolded around a series of content areas. The first content area was digital rhetoric. All the students in this course identified as English majors. As such, we spent time defining “digital rhetoric” and locating our own digital writing practices across technological infrastructures. The second phase of the course structure focused on surveillance and how the rhetorical design of digital infrastructures allows for increased surveillance of bodies and their data. The third phase connected surveillance and digital rhetoric with health and medicine by analyzing the Terms of Service (ToS) and Privacy Policy (PP) of wearables and locating when and how they collect and survey bodies as data. The final phase weaved all of these foundational components together to collaborate with the two chosen UWO health-focused centers: the Women’s Center and the Student Health Center. In this final project, students created digital health campaign deliverables that drew on the foundational knowledge of the course and designed deliverables to increase the health literacies of their peers around particular topics of importance to the two centers.

Considering the Body in Data Collection: Connecting Digital Rhetoric with Conversations in Surveillance Studies

As students in an English Department with a curriculum consisting heavily of literature and creative writing courses, needless to say, we had little prior knowledge of the content presented in this course. Despite the lack of disciplinary knowledge, we all identify as “millennials” and many of us frequently used digital rhetoric infrastructures, such as Snapchat and Instagram, and even used some wearable health technologies, like FitBits and the Samsung Fitness Watch. As such, we drew on our experiences with these products to interrogate the intersections of digital rhetoric, surveillance studies, and its impact on the bodies who use wearable and mobile apps to track health data.

To further enhance our conversations around our lived experience engaging in digital infrastructures, throughout the semester we composed and revised a personal “Digital Rhetoric Manifesto/a”. Drawing on texts like Doug Eyman’s Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice and Danielle DeVoss, Elyse Eidman-Aadahl, and Troy Hick’s Because Digital Writing Matters, we came to understand digital writing as: “the art and practice of preparing documents primarily by computer and often for online delivery.” Yet, this requires the consideration of rhetorical contexts because digital writing “requires attention to the theories and practices of designing, planning, constructing, and maintaining dynamic and interactive texts.[1] Given this, we draw on Doug Eyman’s DRC post to define digital rhetoric as: “the application of rhetorical theory (as analytic method or heuristic for production) to digital texts and performances”.[2] For us, this means that we need to consider how digital infrastructures form identities, build social communities, and produce text.

With our working definition of digital rhetoric established, we began to incorporate issues central to surveillance studies. We believe that the field of surveillance studies is more relevant than ever before. As we noted in the exigency of this course, just in 2017 alone, we have seen cases of mass personal data collection and distribution. Laura Gurak’s Persuasion and Privacy in Cyberspace, while published in 1997 continues to be relevant today, outlining how the collection of mass data places individuals at risk by describing the breach of the Lotus MarketPlace. We learned from Gurak’s book the need for scholars in rhetoric and composition to consider the collection of data as a rhetorical act.

This point, how bodies and data are rhetorically fused together, was further emphasized in Jessica Reyman’s article “User Data on the Social Web: Authorship, Agency, and Appropriation”, which highlights the many ways that user data is collected and appropriated by corporations in the absence of widespread online literacy. Similar to the Lotus MarketPlace case, Reyman explains that “social Web services catalog users’ individual and collective activities across the Internet–aggregating, analyzing, and selling a vast array of data in a practice known as data mining–to be used largely for consumer profiling and target marketing” (514). Reyman’s work emphasizes that users are inadvertently, and in many cases unwittingly, subjecting their data to surveillance and collection. One concern is how these methods of collection often remove data ownership from users. Yet, this often goes unrealized until news stories emerge, like that of the Equifax break. Paying attention and understanding how ToS and PP Agreements often protect the company providing services, and not the individual user, forced us to question how our use of mobile health apps and wearable technologies displace the ownership of our bodily data collected in these applications.

Teaching critical digital literacy relates to the collection and potential surveillance of personal and even bodily data. We see it important then for higher education and, in particular, rhetoric and composition and/or professional writing classes to teach skills to better inform students as users and students as future designers/composers. Establishing critical digital literacy skills enables us, as users, to make informed consent about the collection and use of our personal data as well as consider the ethics of how we design and compose for obtaining consent. For example, take what Estee Beck points to in “The Invisible Digital Identity: Assemblages in Digital Networks.” She urges for users to “become more informed about tracking technologies” and suggests that it is our duty to educate ourselves and others about tracking technologies and privacy on the internet. We take her suggestion and aimed to further reinforce it as we designed our final projects for this class.

Classroom Takeaways Informing Our Projects with Campus Health Centers

Drawing from these readings, and their corresponding assignments (see syllabus), we discussed how we felt personally implicated by our use of these technologies. As such, we came to a classroom understanding that it is our job as users of these digital infrastructures to understand (1) how our use becomes surveilled and privacy is risked and (2) how to be more responsible and educate ourselves about the services we are using. Important to note is that we believe this argument goes two ways. That is, it is also the responsibility of online companies to be honest and straightforward with users. This, we see, requires mobile app and wearable designers and technical writers drafting ToS and PP Agreements to reflect on how users may interact, access, and understand the exchange that occurs when individuals consent to using applications that collect private data, particularly private health information not necessarily protected by HIPPA. As students of digital rhetoric concerned with how digital infrastructures, like mobile health apps and wearables, collect health data, we see a need to model to our peers and other users of these infrastructures more critical digital literacy practices. Further, as potential employees in positions for applications of wearable design and writers for ToS and PP agreements, we seek to reflectively think about how we invite users to understand and ethically consent to use these products–making clear the real risks it may pose to their personal and health information. Coming to an understanding of how our own bodies, as users of these applications, are implicated in the collection of personal data, we considered how our collaborative projects with the UWO Women’s Center and the Student Health Center could serve as campaigns aimed to increase our peer’s understandings.

Designing Health-Focused Campaigns to Encourage Heightened Digital Literacies for Our Peers

For our final project, we worked in teams of two to collaborate with the Women’s Center and the Student Health Center. Representatives from these centers came to our class and discussed their role and current challenges faced on campus. Drawing from those presentations, we reflected on our prior class conversations and projects to create project pitches for these centers. We met with Maria to refine these pitches and ultimately made appointments with our assigned center to go over the details of the project. After receiving feedback from these centers, we again refined our projects to ensure the scope as well as the intentions fit well with the mission and current needs of the center. Below is a summary of the four different projects we collaboratively created.

Readers will see that three out of the four groups created digital media toolkits, which created a series of digital deliverables to be promoted on the health center’s social media pages. While this became a common deliverable, all of these toolkits took it upon themselves to tackle various health-related issues. Only one other group created a different deliverable: a zine. This emerged out of conversations and interest in video game representation shared by student, Jasmine, and Women’s Center Program Assistant, Eliza. You can read more about these campaigns below:

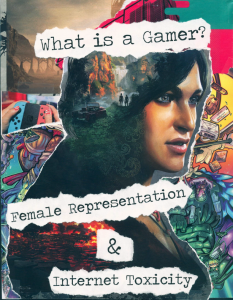

Site One: The Women’s Center

Alyssa and Jasmine’s joint project, in conjunction with the Women’s Center, was the creation of a zine. A zine was an apt medium because it typically focuses on taboo topics and functions as a symbol of resistance. Just as zines are an activist medium, the Level Up! Program, run by Eliza at the Women’s Center, operates with the same activist goals. This zine was created to bring awareness to the inaccurate and harmful stereotypes surrounding female gamers within the gaming community. Additionally, the zine lays out foundational information of the GamerGate scandal of 2014 and female participation in gaming. This information serves to give the reader a platform to understand how opposing toxicity towards women in gaming communities facilitates a feminist definition of equality as well as digital literacy. To access the full version of Alyssa and Jasmine’s zine, follow this link: Level Up! Zine.

Alyssa and Jasmine’s joint project, in conjunction with the Women’s Center, was the creation of a zine. A zine was an apt medium because it typically focuses on taboo topics and functions as a symbol of resistance. Just as zines are an activist medium, the Level Up! Program, run by Eliza at the Women’s Center, operates with the same activist goals. This zine was created to bring awareness to the inaccurate and harmful stereotypes surrounding female gamers within the gaming community. Additionally, the zine lays out foundational information of the GamerGate scandal of 2014 and female participation in gaming. This information serves to give the reader a platform to understand how opposing toxicity towards women in gaming communities facilitates a feminist definition of equality as well as digital literacy. To access the full version of Alyssa and Jasmine’s zine, follow this link: Level Up! Zine.

Tristan and Griffin’s joint project with the Women’s Center was a Digital Media toolkit, which is a detailed campaign focused on using social media, such as, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and/or Snapchat to disperse information related to a cause. This toolkit was developed in conjunction with National Stalking Awareness Month, a campaign that takes place over the month of January to raise awareness and education on stalking. Talking with Alicia, we learned how the Women’s Center provides resources to protect individuals from stalking and that online applications that allow for individuals to mark their locations serve frequently as methods to stalk. As such, we decided to design our campaign around the promotion of more critical understandings around Snapchat, an application frequently used by our peers on campus. Alicia also encouraged us to create a physical brochure that could be handed out by student advisors working in dorms to inform students about the issue. This brochure capitalizes the essence of the online campaign to maximize exposure of how stalking is done via digital technologies, especially with the option to make one’s location instantly known.

Tristan and Griffin’s joint project with the Women’s Center was a Digital Media toolkit, which is a detailed campaign focused on using social media, such as, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and/or Snapchat to disperse information related to a cause. This toolkit was developed in conjunction with National Stalking Awareness Month, a campaign that takes place over the month of January to raise awareness and education on stalking. Talking with Alicia, we learned how the Women’s Center provides resources to protect individuals from stalking and that online applications that allow for individuals to mark their locations serve frequently as methods to stalk. As such, we decided to design our campaign around the promotion of more critical understandings around Snapchat, an application frequently used by our peers on campus. Alicia also encouraged us to create a physical brochure that could be handed out by student advisors working in dorms to inform students about the issue. This brochure capitalizes the essence of the online campaign to maximize exposure of how stalking is done via digital technologies, especially with the option to make one’s location instantly known.

Site Two: The Student Health Center

After learning about the goals of the Student Health Center, Ali and Maddy worked with Juliana Kahrs (UWO Health Promotion Coordinator) to create a digital media toolkit for involving risk reduction and health promotion. Their toolkit contained a different topic for each month that focused on the themes of reducing risk and healthy habits in college. Each month and theme contained photos and facts, as well as helpful hints and tips that the Student Health Center could post on various social media platforms. Some topics included health and hygiene, stress, healthy habits when drinking, and safe sexual habits. Their project will aid the Student Health Center convey messages, on popular social media platforms, about making good choices while in college. Julianna expressed interest in the toolkit as she desired increasing the center’s online social media presence with UWO students. She frequently expressed in their meetings how she looked forward to utilizing relevant and generational information to evoke student interest and help them get involved. As such, the main objective of this toolkit was to create engaging and informative content to foster a better connection between students and the center. We created each post with the intent to increase the center’s engagement with followers and also hope to to recruit additional students to get involved with the center. To view Ali and Maddy’s toolkit, click here: Risk Reduction Health Center Toolkit.

After learning about the goals of the Student Health Center, Ali and Maddy worked with Juliana Kahrs (UWO Health Promotion Coordinator) to create a digital media toolkit for involving risk reduction and health promotion. Their toolkit contained a different topic for each month that focused on the themes of reducing risk and healthy habits in college. Each month and theme contained photos and facts, as well as helpful hints and tips that the Student Health Center could post on various social media platforms. Some topics included health and hygiene, stress, healthy habits when drinking, and safe sexual habits. Their project will aid the Student Health Center convey messages, on popular social media platforms, about making good choices while in college. Julianna expressed interest in the toolkit as she desired increasing the center’s online social media presence with UWO students. She frequently expressed in their meetings how she looked forward to utilizing relevant and generational information to evoke student interest and help them get involved. As such, the main objective of this toolkit was to create engaging and informative content to foster a better connection between students and the center. We created each post with the intent to increase the center’s engagement with followers and also hope to to recruit additional students to get involved with the center. To view Ali and Maddy’s toolkit, click here: Risk Reduction Health Center Toolkit.

Katie and Asher’s collaboration with the Student Health Center also created a digital toolkit as well as a monthly bathroom stall newsletter. The digital toolkit broke down each newsletter explaining what that month’s theme was, as well as listed the links to the articles that were used in the newsletter. The toolkit also contained various content that was shared on the Student Health Center’s social media platforms to promote that month’s theme and newsletter. Each newsletter had a different topic that fell under the umbrella theme of Body Positivity. Some of the newsletter topics included body positive resolutions, National Eating Disorder Awareness Month, Healthy at Every Size, body shaming, and stress. Katie and Asher met with Julianna to discuss what the Student Health Center was looking for, and how they could help. Katie, Asher, and Julianna, agreed that a monthly bathroom stall newsletter was a great way to provide information to students in a way that they cannot ignore. The newsletters introduced the social media hashtag #UWOBodyLove that students would use on their own social media platforms. Katie and Asher also created a spreadsheet for Juliana to track the student use of the hashtag, something that would allow Juliana to analyze how student followers engaged with their social media posts. To access Katie and Asher’s digital toolkit, click here: Student Health Center Digital Toolkit.

Katie and Asher’s collaboration with the Student Health Center also created a digital toolkit as well as a monthly bathroom stall newsletter. The digital toolkit broke down each newsletter explaining what that month’s theme was, as well as listed the links to the articles that were used in the newsletter. The toolkit also contained various content that was shared on the Student Health Center’s social media platforms to promote that month’s theme and newsletter. Each newsletter had a different topic that fell under the umbrella theme of Body Positivity. Some of the newsletter topics included body positive resolutions, National Eating Disorder Awareness Month, Healthy at Every Size, body shaming, and stress. Katie and Asher met with Julianna to discuss what the Student Health Center was looking for, and how they could help. Katie, Asher, and Julianna, agreed that a monthly bathroom stall newsletter was a great way to provide information to students in a way that they cannot ignore. The newsletters introduced the social media hashtag #UWOBodyLove that students would use on their own social media platforms. Katie and Asher also created a spreadsheet for Juliana to track the student use of the hashtag, something that would allow Juliana to analyze how student followers engaged with their social media posts. To access Katie and Asher’s digital toolkit, click here: Student Health Center Digital Toolkit.

Takeaways & Conclusion

As we wrapped up our projects and this course, we realized how much we had developed through this class. Not only were we exposed to new topics and fields of study, but we had created deliverables that would be used on our campus. While at the beginning of this course digital rhetoric felt intangible and unfamiliar, what emerged at the end of this course was an ability to realize that digital rhetoric allows us to study data as rhetorical. Returning to our questions, (1) what is data?; (2) who owns data?; and (3) how, as a digital rhetorician, do these questions about data impact my professional writing practices–we learned from this class that digital rhetoric is always tangible, always impacting and implicating bodies. It impacts users of digital technologies that gather data, and it implicates those who regulate these technologies, designers and the technical writers drafting ToS and PP Agreements. Understanding digital rhetoric as a field of inquiry concerning the body, we felt empowered to create projects aiding the development of more critical digital literacy practices amongst our peers. The continued reports of personal data breaches and the reclaiming of bodies that experienced assault reinforced that, as digital rhetoricians, we must consider the implications of our digital use, design, and compositions in online spaces.

We hope that as other instructors and students read this post, they will consider our experiences from a course that provided opportunities to develop not only as digital rhetoric and professional writing students but as community advocates and collaborators on campus. As higher education and humanities studies face increased pressure to become relevant to “job marketability”, we believe it important to consider how we can position ourselves as students and instructors who support our campus’ organizations and centers.

Authors: Tristan Adams, Asher Erickson, Katie Flynn, Alyssa Herman, Griffin Reese, Alicia Moon, Jasmine Knobloch, Maddy Vasseau, and Maria Novotny

References

Beck, E. N. (2015). The invisible digital identity: Assemblages in digital networks. Computers and Composition, 35, 125-140.

DeVoss, D. N., Eidman-Aadahl, E., & Hicks, T. (2010). Because digital writing matters: Improving student writing in online and multimedia environments. John Wiley & Sons.

Eyman, D. (2015). Digital rhetoric: Theory, method, practice. University of Michigan Press.

Gurak, L. J. (1999). Persuasion and privacy in cyberspace: The online protests over Lotus MarketPlace and the Clipper Chip. Yale University Press.

Jones, N. N. (2016). The technical communicator as advocate: Integrating a social justice approach in technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(3), 342-361.

Reyman, J. (2013). User data on the social web: Authorship, agency, and appropriation. College English, 75(5), 513-533.

[1] http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/10.1/coverweb/wide/popups/popup_digital.html [2] http://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2012/05/16/on-digital-rhetoric/