Presenters: Rachael Sullivan (Saint Joseph’s University), Sean Milligan (Wayne State University), Kristi McDuffie (University of Illinois), and Melissa Ames (Eastern Illinois University)

The panel “How and Why Digital Rhetoric Matters” provided attendees with the opportunity to think through the ways in which digital rhetoric is used as a tool to express and circulate political ideas. While each presentation focused on a different facet of digital rhetoric—memes, a cartoon, and hashtags—together, they all asked thoughtful questions about the ways in which these means of expression can have harmful or helpful intentions.

Rachael Sullivan, “Misogyny by Design: The Visual Ethics of Political Meme Circulation”

Rachael Sullivan’s talk began by answering the question, “How did online meme culture contribute to the pervasiveness of misogyny during the 2016 election cycle?” Drawing on the work of Wendy Phillips and Ryan Milner, as well as Susan Hilligoss and Sean Williams’ use of visual ethics as a framework for understanding internet memes, Sullivan analyzed misogynistic memes of Hilary Clinton during the 2016 election cycle. She explained that such memes silence women and “package misogyny to make the content of the meme seem like just a joke.”

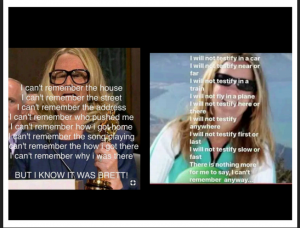

To show how misogynistic memes persisted beyond the 2016 election cycle, Sullivan shared two memes with Dr. Christine Blasely Ford;she explained how one meme is fake news—“it uses a photo from the internet [not of Ford]and tries to pass it off as Ford,” and how the other meme “turns Ford’s accusation into a child’s game” by covering an actual photo of Ford with a Dr. Seuss style poem. To end her talk, Sullivan explained how the Time magazine done by John Mavroudis where Ford’s body is materialized using her own words can be an example for students of an ethical, text heavy, political meme. Sullivan described an assignment where students could choose a political figure and then illustrate that figure as best they can using the words that figure has spoken. For Sullivan, even though memes can be problematic, they have a place in our Composition classes and can facilitate students’ engagement in conversations about the problems, production, and circulation of political memes.

Sean Milligan, “Pepe, Zaniness, and Post-Truth Rhetoric”

Following Sullivan, Sean Milligan argued in his talk that zaniness, which played a prominent role in the 2016 political election, is a defining political and rhetorical strategy. Milligan used Sianne Ngai’s concept of zaniness as a framework for analyzing three distinct moments in the rhetorical life of Pepe—his initial appearance, his appropriation by the alt-right, and his adoption as unofficial propaganda for the Trump campaign.

To show how Pepe the frog evolved from a cartoon in Matt Furie’s comic The Boy’s Club to unofficial propaganda for the Trump campaign, Milligan analyzed the “Feels Good Man” comic from The Boy’s Club in which Pepe “summarizes the ethos of Boy’s Club of fun and self-gratification.” Milligan then described how Pepe was picked up by and really resonated with internet trolls because he does not care about the reactions of those around him to his behaviors. Like Pepe,

trolls engage in problematic internet behavior “because it feels good, man.” Since Trump adopted a rhetorical mode that can be understood as trolling, trolls saw Trump as one of their own—someone whose offensive and problematic comments could not be blocked by a social media site. This then led to Pepe becoming associated with the Trump campaign, mirroring the function Pepe served in alt-right circles. Milligan acknowledged that while Pepe wasn’t official propaganda, he became the most natural figure of Trump’s politics because, like Pepe’s behaviors which aren’t to be taken too seriously, Trump’s comments are also minimized by being described by supporters as “just a joke” or “trolling.”

Kristi McDuffie and Melissa Ames, “Affecting Digital Activism: A Comparative Study of #MarchforOurLives”

In the final talk, Kristi McDuffie and Melissa Ames shared the most common rhetorical strategies they found in their analysis of over 200,000 tweets from #MarchforOurLives and #WomensMarch. Their presentation explored how hashtag activities can be employ affect to accomplish movement goals. Throughout their presentation, they shared some of the most common strategies they noticed:

- The use of personal narrative and first person plural (“On our way to celebrate the power of unity! Your cause is our cause”)

- Calls to Action (“We’re here, are you?”)

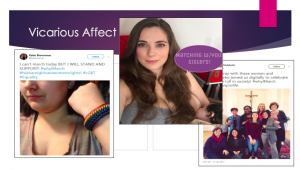

- Vicarious Affect (“Marching via Twitter”)

- Collective Affect (“Today we stand with our youth, in awe…”)

Examples of the use of personal narrative and first person plural can be seen in tweets that explain why participants march, vignettes of misogynistic personal encounters with men (often on the way to the march) from #WomensMarch, and for #MarchforOurLives a large theme of personal narratives from veterans. As McDuffie and Ames explained, calls to action for #WomensMarch include tweets that encouraged folks to participate in the marches and also often had a dominant focus on emotion like hope, pride, love, or gratitude, while calls to action from #MarchforOurLives were more indicting. In their description of vicarious affect found in tweetswhere users acknowledged that they were participating virtually and expressing solidarity from afar, I was reminded of Margaret Price’s description of telepresence and the ways in which such march participation makes the space accessible to a variety of bodies. In their description of collective affect, McDuffie and Ames shared tweets that shared positive affect and erased the divide between self and others, as well as that projected feelings onto participants.

Takeaways

I appreciated how these presentations encouraged me to think about the ways everyday aspects of digital media can become positive and negative tools for change. As an instructor of first-year writing, Sullivan, Milligan, McDuffie, and Ames had me thinking about how the everyday forms of digital rhetoric our students regularly engage with can be tools for understanding rhetorical design and circulation, as well as intent. In other words, their panel made me think about how writing instructors can use digital rhetoric with a variety of intentions as an instructional tool, and I’m looking forward to bringing the lessons I learned from these panelists into my teaching.