Presenters: Samantha Blackmon (Purdue U, West Lafayette) and TreaAndrea Russworm (U of Massachusetts)

For a session starting at 8:30 in the morning, there are few empty seats as the panel, a critical consideration of the portrayal of race in video games, begins. Samantha Blackmon and TreaAndrea Russworm share nuanced and future-focused analyses of popular Triple-A titles, attending especially to the games’ cultural contexts: how they function in conversation with other games released around the same time and how their representations of race affected how they were received by the public. The session concludes with a lively conversation with the audience that meanders from questions about procedural cinema, to the persuasive potential of games as a medium, to the productive discomfort and honesty of glitches.

Samantha Blackmon, “‘There Are Only Two Paths’: Problems and Possibilities in Far Cry”

Blackmon begins by introducing the game at the center of her analysis, Ubisoft’s Far Cry 5, an open world first-person shooter where the player is part of a resistance against the despotic leader of a religious cult. She characterizes the game as a turn toward American pastoral, an opportunity for gamers to play as heroes in the fictional Hope Country, Montana. Her analysis, she explains, explores the game’s problems and possibilities, using as artifacts the announcement trailer, marketing, and the first twenty to thirty hours she had played at the time she was carrying out this work.

Grounding her presentation in a text we could share, she plays the original announcement trailer from 2017, before considering the connections and intersections between Far Cry 5 and other games released not long before that, which were similarly steeped in contemporary political drama. While Far Cry 5 features a charismatic cult leader that looks suspiciously like David Karesh (“they’ve even got the same glasses!” Blackmon quips), Mafia III is similarly inspired by the real world: Martin Luther King, Jr., the Vietnam conflict, and the effects of drugs on communities of color are intertwined with the fictional narrative. Bethesda’s Wolfenstein II features Nazis in full regalia and hearkens back to a time that has been called “great” in our current political climate, a time of Beaver Cleaver and Richie Cunningham.

Grounding her presentation in a text we could share, she plays the original announcement trailer from 2017, before considering the connections and intersections between Far Cry 5 and other games released not long before that, which were similarly steeped in contemporary political drama. While Far Cry 5 features a charismatic cult leader that looks suspiciously like David Karesh (“they’ve even got the same glasses!” Blackmon quips), Mafia III is similarly inspired by the real world: Martin Luther King, Jr., the Vietnam conflict, and the effects of drugs on communities of color are intertwined with the fictional narrative. Bethesda’s Wolfenstein II features Nazis in full regalia and hearkens back to a time that has been called “great” in our current political climate, a time of Beaver Cleaver and Richie Cunningham.

Blackmon ultimately argues that Far Cry 5 held so much promise for picking up the antiracist mantle where Mafia III and Wolfenstein II left off. When Bethesda was accused of attacking “Patriots” in Wolfenstein II, the company doubled down on its anti-Nazi campaign on its social media pages. Ubisoft, however, did the opposite. Blackmon posits that this may have been an attempt to avoid ostracizing their conservative fan base, or, giving them the benefit of the doubt, it could be due to poor narrative worldbuilding. Either way, she argues, the marketing falls short of a justice-orientation, and the game does no better, uncritically characterizing the militia and survivalists as protagonists, painting a problematic image of utopian inclusion, and shaming women’s sexual desires. Although Blackmon has seen indie titles working to resist our culture’s racist metanarratives, she argues that it would be productive to see this work done on a larger scale.

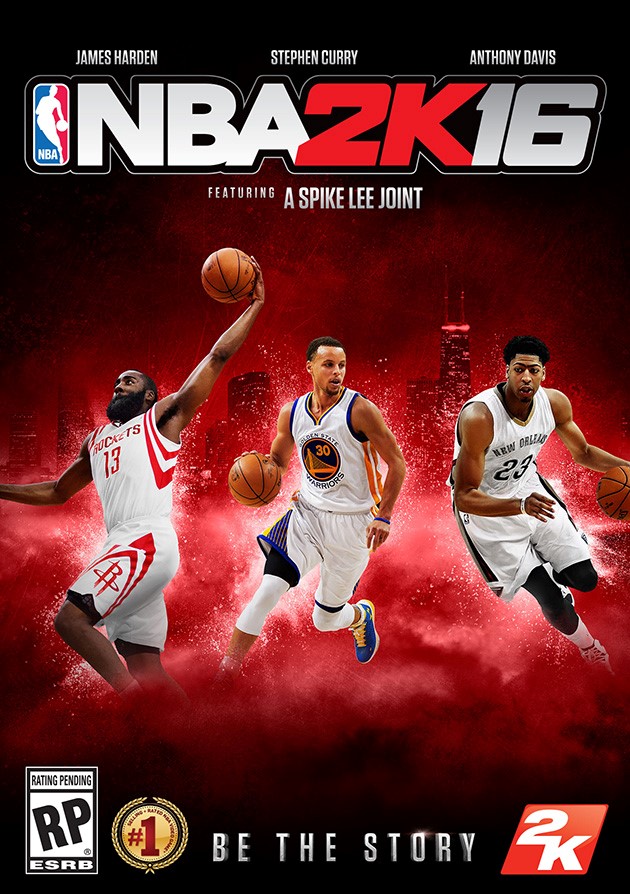

TreaAndrea Russworm, “Computational Blackness: The Procedural Logics of Race, Game, and Cinema, or How Spike Lee’s Livin’ Da Dream Productively ‘Broke’ a Popular Video Game”

Russworm presents her analysis of NBA 2K16’s career mode, which is comprised of a collection of non-interactive cut scenes. She plays the opening of the game for us, which begins very self-consciously as live-action cinema of the actors rehearsing and Spike Lee in front of the camera, before it shifts to digital. In the wake of this innovative approach, other black sports video game franchises followed suit, similarly presenting cinematic experiences about race. The film within a game formula became an aspirational aspect of the genre, yet Lee’s contribution was criticized by mostly nonblack gamers who called it broken. Russworm’s work examines the persuasive power of video games by inspecting how video games function as computational systems through narrative, plot, and characterization. She considers how elements of customization and control granted to the player through adjustable sliders change the gaming experience and indirectly convey meaning. In other words, players control the embodied pixels representing the athletes and other elements of the game, which raises questions about black embodiment and containment.

While Russworm examines NBA 2K16 through a critical lens, noting that the discovery that the protagonist’s best friend has died unlocks an achievement and that a pathos of suffering and survival is supposed to prepare the protagonist for his experience in the NBA, she also argues that Lee’s story works to add depth to the game, and empathetic characterization. She considers the functionality of this material, this procedural cinema within a game, a spectatorial experience not usually associated with the medium.

Russworm finds in Spike Lee’s contributions an element of resistance to procedural racism, even as the game insists on procedurally rendering problematic images of black identity. The criticism of the game as “broken,” levied by mostly nonblack gamers, coalesces around the game’s insistence that the player character be a member of a black family, have a black twin sister, and be subjected to racist remarks, regardless of how that character is customized—as black, or white, or Asian. Russworm, however, resists this critique and instead explores how these choices illuminate the nonsensicality of procedural racism by forcing the player to maintain a biological connection to blackness. While players have the autonomy to insert themselves into the context of the story, the family’s representation will not change. The notion of gamer autonomy is critiqued as their agency is compromised, as the game eschews interactivity in favor of cinematic content. This, Russworm argues, unsettles the procedural logics of video games, and in the end, “Livin’ Da Dream” is neither game nor cinema but procedural cinema—expressive, rhetorical—subordinating long-held player expectations to control digital black bodies at will.

Conclusion

Together, the presenters provide an insightful and evocative conversation on the persuasive power of videogames as a storytelling medium, the ways games can work to reflect or resist problematic social narratives, and how gamers’ existing ideologies can interface with the game to affect reception and uptake of the intended message. As we consider the ways in which popular culture narratives shift, disrupt, or perpetuate racist and misogynistic identities and ideologies, we must always keep an eye on the broader context from which the game was born.