I had the pleasure of attending CCCC 2019 Digital Praxis Poster Session C on Thursday, March 14, 2019. At the broadest level, sessions addressed critical engagement with digital interfaces and shared an emphasis on the need for ethical intervention in digital reading and writing practices as particularly vulnerable sites of composition.

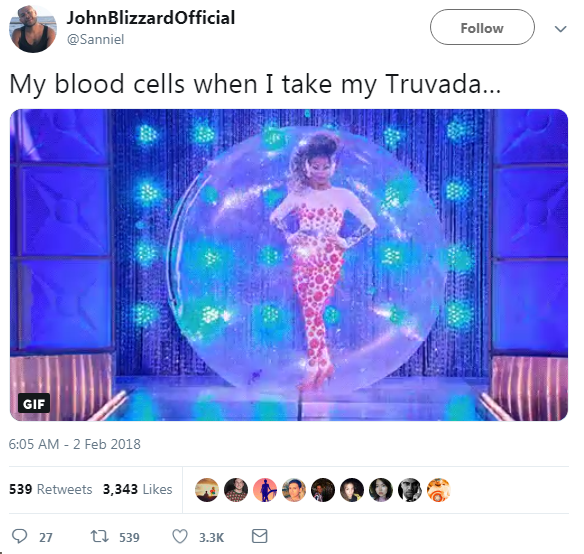

Wilfredo Flores (Michigan State University), “‘My Blood Cells When I Take My Truvada’: Examining Twitter Users’ Engagement with PrEP, Truvada, and Sexual Health”

Flores’s work-in-progress started upon recognizing the rhetorical complexity of the “My Blood Cells When I Take My Truvada” gif.

The gif-turned-viral-meme inspired Flores to further investigate the following key question: how do users tweet about sexual health (specifically, PrEP and Truvada) and, at the meta level, how do researchers execute ethical methods when working with user-generated data in social media contexts? Flores emphasized that documenting “who is tweeting what” is not where the most significant research labor lies—tags take care of half the battle (see https://tags.hawksey.info/). Rather, we should be concerned with accounting for the people’s lives behind the data. Studying population health/health communication in this way is an interdisciplinary endeavor (medical humanities, cultural rhetorics, etc.) that must involve not only effective grounded theory coding practices (Flores relies on Saldaña, The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers) but also an ethical approach to data collection and interpretation (Flores advocates starting with the guidelines of the Association of Internet Researchers). We commiserated over institutional review board “fuzziness” (my words, not Flores’s) in shepherding ethical digital research, and, ultimately, Flores invoked Malea Powell to highlight the importance of using cultural rhetorics as an integral framework for interpreting social media data. It’s people’s stories—people’s lives and bodies—, not just words on the screen, that are at stake.

Charles Woods (Illinois State University), “Uncovering Clues Using GEDmatch.com: Considering the Ethicality of Big Data’s Influence on Police Tactics”

Woods brought this message to bear in a strikingly tangible way. The exigence for Woods’s research is situated in the case of the capture of the Golden State Killer.

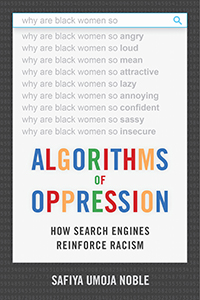

In short, police used GEDmatch.com and the reconstruction of a family tree from a third cousin to apprehend Joseph James DeAngelo. Regardless of one’s thoughts on whether the perpetrator received the outcome he deserved, Woods calls us to interrogate the online use of genealogical databases for catching criminals in digital and non-digital spaces. There is precious little ethical oversite in this regard—a small paragraph in a lengthy user agreement, if you’re lucky—and it is marginalized bodies and communities that suffer the disproportional negative consequences. Woods advocates for extending conversations of virtue ethics (J. Gallagher, “Enacting Virtue Ethics,” Rhetoric Review, vol. 37) and bringing the triangle of medical rhetorics, consent, and big data more prominently into those conversations. Woods operates from a technical communication framework and discussed extending such research into case studies of company user agreements and user consent. Where should one start if they are interested in joining the conversation? Woods recommends S. Nobles’s Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, among others. Want to talk more about identity formation & curation in digital spaces, digital rhetorics & Big Data, and writing studies pedagogy? Get in touch with Woods.

Kamila Albert (Florida State University), “Remediation, Composing across Media, and Writing Centers”

Finally, I engaged with Kamila Albert. I am a writing center director and rhetoric, technology, and digital writing specialist, so I was curious what Albert might have to say about educating writing center consultants in digital literacy practices. Albert described her experience as coordinator of her institution’s Digital Studio, which is connected with but distinct from their writing center. Consultants generally spend five hours per week tutoring in the writing center and five hours per week assisting in the Digital Studio.

The dilemma Albert faces is knowing that her consultants may or may not begin their job with well-developed technological literacies—or at least with the confidence to assist other writers in the more technical aspects of a composing technology-rich writing assignment. Albert relayed that consultants receive six weeks of summer training prior to beginning work in the writing center, but the more technical training required for Digital Studio work begins on the job and is often executed in voluntarily attended workshops that she designs based on pre-semester assessment surveys. She delivers these training workshops in large groups or one-to-one; she also employs a deliberate mentorship structure. Because tutors are required not only to assist in individual and small-group ways but also to facilitate larger-group workshops, she asks consultants to observe the tech workshops she delivers—with tutors eventually assisting in and facilitating their own workshops with greater confidence.

We agreed that things like Adobe InDesign, Adobe Photoshop, video editing software, etc. (the most apropos tools for the common media-rich assignments proctored at her institution) take time to learn, which is why she advocates that writing center coordinators check-in with staff on a regular basis. More uniquely, she advocates remediation as a foundational way to make tech-rich writing tutor education more accessible. Using remediation as a lens allows even the most technology reticent consultants to start with something they know and to have confidence in and to develop a critical understanding of the rhetorical choices at stake in remixing writing in new and different modes, said Albert. One particularly important theoretical touchstone for Albert is Joy Bancroft’s work on spanning the digital divide in multiliteracy centers. I have also researched this issue and invite you to visit WLN’s Digital Edited collection: How We Teach Writing Tutors.

Takeaways

At this point, you might be wondering, what does training writing tutors in effective technology-rich writing assistance have to do with the ethical collection of data from digital social spaces such as Twitter or GEDmatch.com? The answer is everything. What I took away from these presentations was an interest in and concern for public critical literacy, especially in digital spaces. Just because many of our students have grown up digital natives does not mean they possess functional or experiential technological literacy and especially not critical literacy (see Adam Banks’s notes on access, Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground). Our job as digital researchers and pedagogues is to make the invisible visible again, to help our students, who are already participating as professionals and citizens in these digital public social spaces, see the way interfaces mediate our interaction with real people. A cultural rhetorics approach to composing ourselves and researching within these vulnerable spaces is 100% necessary.

While I didn’t get to dialogue in depth with Ann Amicucci (University of Colorado, Colorado Springs) about her project “Expert/Vulnerability: Designing a Rhetoric of Social Media Course,” she well captured an important theme here: composing ourselves in digital spaces is an inherently vulnerable act, but one we must be willing to engage in with critical acumen. In Amicucci’s words, “experimentation is always valuable. It is always worth your time to be vulnerable and to experiment.”