Speakers: Jennifer Baine (South Arkansas Community College, El Dorado), Jennifer Burke Reifman (University of California, Davis), and Thomas Geary (Tidewater Community College, Virginia Beach, VA)

Presenters in this panel all focused on the ways that technology offers teachers chances to take into account the humanity of their students, open up further access to composition, and provide increased reflection on writing as process. While each speaker engaged in various levels of technology use in the session, each spoke of benefits of technology specific to our two-year colleges that much of the research has ignored by focusing exclusively on four-year colleges and universities. All advocated that we, the listeners and readers of their messages, had much to contribute to this growing and necessary field of study.

Jennifer Baine, “Leveraging Tech to Navigate Barriers to Success”

Baine began by discussing her own experiences approaching technology as content her class needed to cover. When some of her colleagues mentioned that this was too much “hands-on/hand-holding” teaching, Baine researched the barriers to student success. At this point, she engaged us to think about the barriers our students face at two-year schools, and many of us provided familiar answers like “Reading for the main point,” “Critical reading,” and “Lack of familiarity with technology or campuses.” Baine continued with her research, which listed other critical concerns, such as “Remediation,” “Faculty approaches or attitudes,” and “lack of family or social support structures.”

To help two-year college students, many of whom are first-generation college students and many of whom work multiple jobs, Baine suggested leveraging technology to help students overcome the barriers we provide them. For example, she highlighted ways to help students with multiple jobs or childcare issues through recorded classes, live-casting classes, and storing notes online. Further, online resources for quizzes and books help make materials more available past attendance and budgeting concerns that many two-year college students face. Finally, she mentioned helping students understand how to sync calendars from course management systems and extending offers to network through Linked-In in addition to attendance at school functions. All of these uses of tech further democratize our classrooms, meeting students where they live rather than forcing them to live within the confines of a more traditional educational environment, from which many of them already feel excluded.

Jennifer Burke Reifman, “Purposefully Incorporating Tech in BW through Critical Digital Literacy”

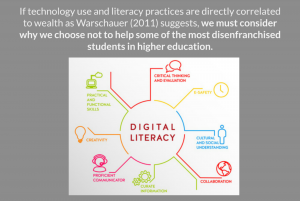

Reifman turned the conversation away from how to meet students where they are with their barriers and instead discuss the ways in which we can engage students with conversations about how the technology they already use might be exerting influence and control on them. Reifman states emphatically that Literacy is inherently linked to Digital Literacy: if we as members of NCTE agree that literacy is at the front of what we do, then Digital Literacy necessarily belongs in our classrooms.

Along with this Digital Literacy, however, Reifman reminds us that many users of digital services do not possess training in critical literacies: they consume social media passively, without evaluating the impact it has on daily life. Reifman draws on Yancey’s call for the NCTE to deal with 21st Century Technologies by engaging Basic Writers (regardless of the term assigned to them after legislative removal of remediation) through analyzing, criticizing, and evaluating technology to help them identify and question power structures. Reifman presented multiple assignments she uses to focus on Critical Digital Literacy, including social media use analysis, meme analysis, side-by-side comparison of a hard copy and digital comic, a personal inquiry project, a digital literacy narrative, and a research-based blog post on a blog Reifman maintains. These assignments all invite basic writers to analyze digital writing and compose in digital spaces for live audiences but also encourage active peer review through students commenting on each other’s blog posts.

Thomas Geary, “Soundwriting as invention in FYC”

Geary closed out the session with a presentation about soundwriting, a term he prefers to aural or sonic rhetorics because of its emphasis on creating meaning out of manipulated sounds. He opened with a student’s collage of sounds associated with the term “success,” which includes a champagne cork popping, video game reward sounds, and other brief sounds strung together (published by permission of the student creator and the presenter). Opening with this composition foregrounded the unique work he requests of his students.

Geary contends that soundwriting emphasizes process writing, from which basic writers and first-year students can especially benefit. With the rise of mobile technology use, most students have access to mobile phones or laptop computers that will allow them to use Audacity to compose with sounds. Sound compositions range from definitions, like the sample in the introduction, to digital storytelling or creating podcasts. And, while Geary notes the multiple ways students can interact with these assignments, he also notes that alternative assignments need to be available for students with problems of access, whether economic- or disability-related.

Takeaways

[photo credit: by Manuel Sardo on Unsplash]