Presenters: Rebecca Hudgins (The Ohio State University), L. Corrine Jones (University of Central Florida), and Emily Mattern (Northeast Ohio Medical University). Elizabeth Miller (The Ohio State University) was unable to attend.

Almost as long as the internet has been available to the general public, people have used the expansive collection of data for medical reasons. The sophistication of technology has only added to this trend, as websites like WebMD entice the ill with prospective answers to their medical problems. The presenters of the panel Digital Bodies, Digital Disability: Performing Health Online examine four such spaces as they discuss the agency patients have when medicine migrates to the internet. While listening to these presentations it becomes clear that in a digital space, patient agency can easily be compromised. Based off the findings of the panel participants more research is needed into this phenomenon.

Rebecca Hudgins, “PatientsLikeMe.com: The Future of Empowered Patients”

Rebecca Hudgins begins the panel explaining her husband’s difficulties in mediating the healthcare system after a diagnosis of Fibromyalgia. With multiple twists and turns, hoops to jump through, and dead ends encountered, Hudgins and her spouse turned to the internet, specifically a website called PatientsLikeMe.com. The website is an online forum where patients of different diseases can congregate and gather support from those suffering as they are.

The site not only caters to the disabled public, it also allows researchers, doctors, and medical professionals to view forms as well. Hudgins suggests that this space has a duality to it. On the one hand, the space allows communication to flow freely from one disabled individual to another, which empowers patients to take control of their disability, their health, and their situation. On the other hand, when patients show doctors this newfound knowledge, it can sometimes lead to a breakdown in communication. Some doctors use these websites as a space to send patients so that they do not have to explain the diagnosis in detail. Such doctors use this method to save their own time, leaving the patient to work through their diagnosis alone.

Hudgins calls for further examination of these spaces and their use in the medical profession.

Corrine Jones, “Rhetorical Actancy In the Human Diagnosis Project”

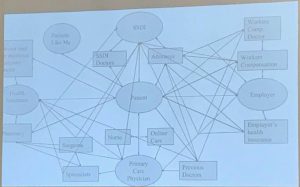

Corrine Jones further examines the difficulties of rhetorical representation for patients online when she discusses the Human Diagnosis Project. This is an app where patients can upload their medical information and then have researchers, doctors, and medical professionals view the forms to practice differential diagnosis. Jones focuses on the issues with this site. One such issue is the rhetorical decisions that went into its creation. The site has yet to create a method where patients and researchers can discuss the diagnosis; patients upload their medical records and researchers provide diagnosis, communication after that is restricted.

Another major part of Jones’s argument is that the program uses predictive text boxes, which are programmed by outside sources. These predictive text boxes can have an influence on how prescribers choose their diagnosis. Jones says, “The diseases that appear in the predictive text boxes and are available to doctors therefore represent rhetorical choices made by the app designers.” Rhetorically, this means that the programmer is the one who potentially is deciding which diseases to include and which to exclude, or which bodies matter. She also argues that “to the disability community, this work recognizes that disabled persons are still struggling to have agency over their bodies when interacting with doctors trying to treat them.” This means patients do not always have the potential to influence how they are perceived in the app. Since patients have little access through the app, they cannot make changes, discuss diagnosis, or even humanize themselves to their prescribers.

To the digital rhetoric community, Jones calls for more exploration into how coding predictive text boxes includes and/or excludes certain bodies from participation. Ultimately, the coding of such boxes requires a coder who makes the decisions of what options will appear, meaning they decide which bodies are important (or in the case of the app, which diagnosis are important). This exclusion is an intersection where digital rhetoric and disability collide.

Emily Mattern, “Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs: Patient and Physician Influences”

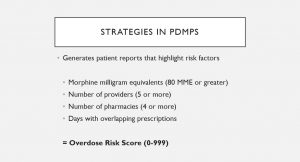

Emily Mattern uses Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMP), which was developed in response to the opioid crisis, to examine the preconceived notions that arise from digital documentation. A major reason for PDMP was to discourage doctor or pharmacy shopping, an activity where patients visit multiple doctors for multiple prescriptions, either to fuel their addiction or to sell. Mattern admits that the PDMP system has decreased the number of doctor shoppers and pharmacy hoppers since its conception, but she also argues that this is not the whole story.

The PDMP scale is constructed based on a collection of data provided by multiple sources. This data is translated into a score, which suggests the patient’s susceptibility to opioid addiction. What is not included in this data set is the patient’s narrative or history. This vital qualitative data is necessary for physicians to make a proper diagnosis.

Another problem with PDMP data is that patients do not know their score, nor can they find this information on their own. It is up to the doctor to disclose this information to the patient, and Mattern suggests many physicians do not take the proper time to disclose or explain the score to patients. If doctors do disclose the score to a patient, they do not always explain what the score means, or they may not take the opportunity to discuss treatments for addiction. Mattern argues that revealing a patient’s score is a great time to discuss their risk of addiction and treatment options for opioid dependency. However, physicians are not required to do this, and there is a possibility many may not.

It becomes apparent that, again, the patient is the one excluded from this information. Patients cannot access their own records and more than likely do not know what their scores mean. Beyond this, Mattern suggests that the data used in these reports does not take into consideration important factors which can increase or decrease a patient’s likeliness to abuse opioids or narcotics. The final diagnosis is up to a doctor, and it is unclear how many physicians will account for patient narrative when using this score with, on, and for patients.

Takeaways

- In a digital space, patients can lack the ability to act rhetorically with others, especially medical professionals. While medical professionals can move freely around these digital spaces, the patient does not always have control of who sees their information, how it is received, or what is or is not considered in the diagnosis process.

- Digital spaces have the potential to create barriers for proper communication to flow between patients and medical professionals. Anyone included in the process is then responsible for helping to mediate this communication; from patients, to physicians, to computer programmers.

- Databases like the ones mentioned here rely on quantitative data and should be used while considering the qualitative data of patient history and narrative. While these spaces can be helpful, they do not replace personal interaction in the assessment process.

- Such databases also create classifications of patients, which needs to be further explored for its rhetorical significance. Whether it is a medical professional labeling a patient or a patient self-identifying with their diagnosis, these spaces are places where rhetoric happens on the internet.

I want to thank the presenters of this panel for their cooperation and openness for this review. I appreciate how accommodating you all were and thank you for your contribution to the field. All images used in this work are the property of the presenters and were used with permissions.