Designing the Course: Kristi’s Project

How does the digital change what we know about and how we practice rhetoric and literacy? This broad question framed the master’s level Digital Rhetoric & Literacy course I taught in Fall 2018. Students who take this course come from across our degree options in rhetoric & composition, literature, and TESOL and have a wide variety of undergraduate backgrounds and professional goals. With this in mind, I wanted to provide students with opportunities to answer that broad question across personal, academic, professional, and civic dimensions.

I assigned several texts that engage with multimodal design because it is key to contemporary rhetorical and literate activity. And because so much of our work in rhetoric & composition is social advocacy work (variously situated in academic institutions, workplaces, and public spaces), many of those texts set students up to engage with design advocacy ideas and practices explicitly (e.g., Buck, 2008; Eyman, 2015; Haas, 2007; Mathieu & George, 2009; Noble, 2018; Selfe & Selfe, 1994; Sheridan et al., 2008; and Wysocki & Jasken, 2003; among others).

Because of my students’ wide-ranging interests—and because of the kinds of projects encouraged through our course readings and software workshops—I wrote an open-ended assignment for their seminar project:

There are two requirements for your final project:

- It needs to engage the issues we’re taking up in this class.

- It needs to do work that is useful for you (intellectually, professionally, civically, and personally).

The assignment then outlined three possibilities:

- a fairly traditional seminar paper or digital project that builds some kind of researched argument about digital rhetoric and/or literacy,

- a course unit for high school or undergraduate students that teaches something about digital rhetorical and/or literate practice and/or theory, or

- a digital project that does rhetorical and/or literate work in the world for a particular audience.

The prompt concluded with two issues for students to reflect on:

- Keep in mind your (even tentative) plans for post-degree life. What kind of project would best help you work toward that?

- Consider the range of digital technologies we are working with in this class […] as well as those that you might already know or want to learn outside of class. How might you might leverage those technologies to build the kind of project you want to create?

Three student projects in particular serve as excellent examples of what Jiang & Tham (2019) call design advocacy, or “social justice initiatives actualized through design.” The first example of student work, below, comes from Casey J. Marshall. Casey undertook the first option to craft a digital researched argument advocating for instructors’ use of Universal Design principles in online writing classes.

The second and third examples—which are discussed in a separate post—come from Malia Ruehl and Rain Vivant, who both pursued the third option, a digital project meant to do work in the world. Malia’s crowdsourced database project, The Warren, seeks to orient those new to rhetoric & composition by making visible the connections among scholars’ work. Rain built a social media plan for a nonprofit organization supporting affordable housing initiatives in Southern California’s Inland Empire.

Universal Design for Online Teaching: Casey’s Project

How can we design online learning spaces that accommodate people with a diverse set of needs? This is the question that my project sought to answer. Living with disability often involves embracing multimodal rhetoric through adaptive technology. For example, captions are a type of visual rhetoric for people with auditory impairments, and voiceover is a type of aural rhetoric for those with visual impairments. Universal Design in Education (UDE) is the practice of striving to create inclusive learning spaces that accommodate the maximum variety of needs (Burgstahler, 2012). What would an online classroom that follows UDE incorporate?

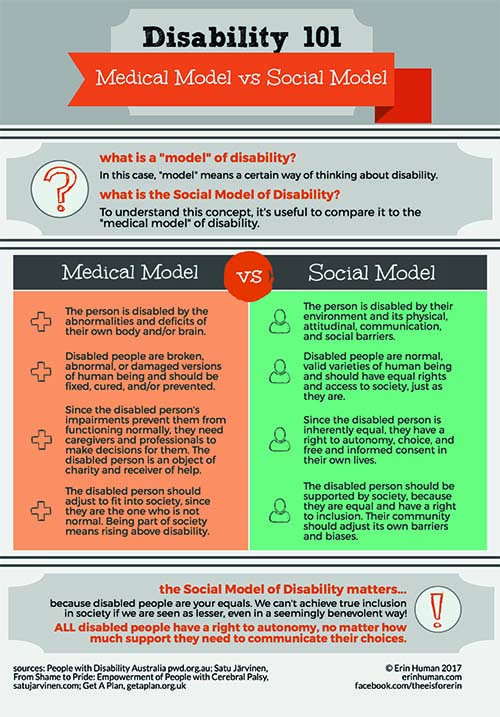

First, we need to define disability in this context. Two major models of disability are the Medical Model and the Social Model. The Medical Model defines impairments that are then clinically named and treated. In contrast, the Social Model says that disability is something designed by society; someone is not disabled until they have a need that is not met by the way society is designed. UDE argues that everyone shares the needs arising from disability. Working from the Social Model, UDE shifts educators’ focus away from the needs that disability creates for those born with impairments and toward the society that creates situations in which disability arises.

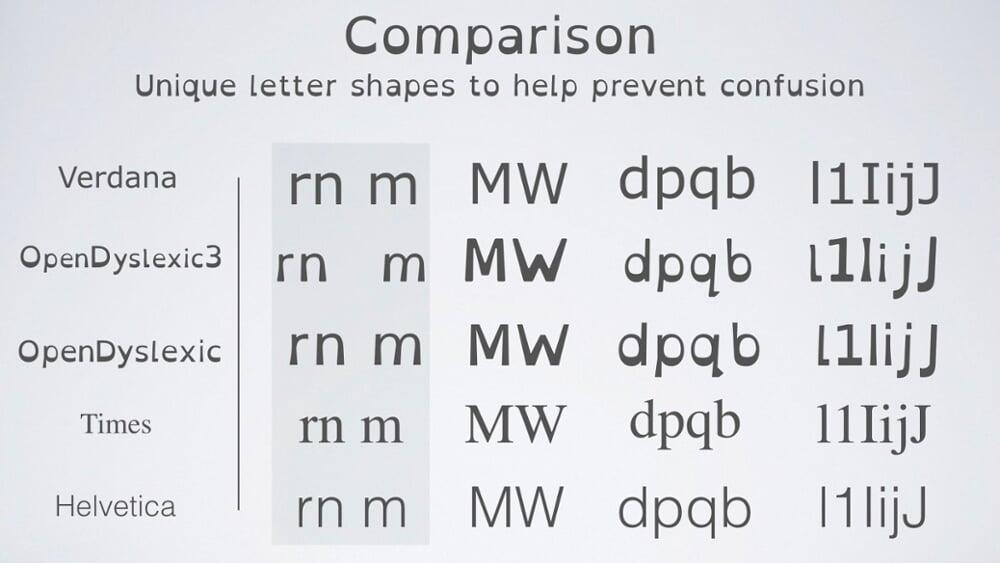

My project asserts that online instructors using UDE need to implement these principles across all modes of communication. For example, online learning spaces need to address the complexities of visual and spatial communication, while still allowing for instructor customization. Text should be organized with attention to size, spacing, color, and font (e.g., Serafini, 2014 on elements of visual composition). Like other disabilities, dyslexia can be a product of visual design and can be mitigated with common fonts such as Helvetica, Arial, and Verdana (Baeza-Yates & Rello, 2013). However, the ability to customize any interface is still necessary for displaying certain formats, like poetry.

We utilize aural cues every day, from the sound of pressing keys on our devices to following audio signals in crosswalks. The ability to narrate visual rhetoric with audio is common in many smartphones and computers, but this narration is just an approximation of the visual. It lacks the “aural strategies” Rodrigue et al. (2016) explore. How does aural rhetoric sound when it isn’t approximating other modes of communication? This is a question that instructors should ask when making aural accommodations online.

Ultimately, UDE is more aspirational than universal. Teachers will also change, along with our very understanding of ability and disability. Whose lives are materially supported with health care and equipment? Who can teach? The nature of disability changes with the design of society itself. Design cannot be universalized: the criteria of UDE must be open to change as society, technology, and modes of communication change, creating new rhetorics and new affordances for new designs. My project ultimately argues that UDE must be adaptable as future instructors redesign our available designs (New London Group, 1996) for changing needs.

Read the second and third student projects in this next post.

References

Baeza-Yates, Ricardo, & Luz Rello. (2013). Good fonts for dyslexia. ASSETS. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from http://dyslexiahelp.umich.edu/sites/default/files/good_fonts_for_dyslexia_study.pdf

Buck, Amber. (2008). The invisible interface: MS word in the writing center. Computers and Composition 25, 396–415.

Burgstahler, Sheryl. (2012). Universal design in education: Principles and applications. Washington University DO-IT Center. Retrieved December 14, 2018, from https://www.washington.edu/doit/universal-design-education-principles-and-applications

Eyman, Douglas. (2015). Digital rhetoric: Theory, method, practice. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Haas, Angela. (2007). Wampum as hypertext: An American Indian intellectual tradition of multimedia theory and practice. Studies in American Indian Literatures, 19(4), 77–100.

Jiang, Jialei, & Jason Tham. (2019, February 5). Multimodal design and social advocacy: Charting future directions for design as an interdisciplinary engagement. Gayle Morris Sweetland Digital Rhetoric Collaborative. Retrieved March 30, 2019, from http://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2019/02/05/multimodal-design-social-advocacy/

Mathieu, Paula, & Diana George. (2009). Not going it alone: Public writing, independent media, and the circulation of homeless advocacy. College Composition and Communication, 61(1), 130–149.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–93.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Rodrigue, Tanya K., Kate Artz, Julia Bennett, M.P. Carver, Megan Grandmont, Dan Harris, Danah Hashem, Anne Mooney, Mike Rand, & Amy Zimmerman. (2016). Navigating the soundscape, composing with audio. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 21(1). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/21.1/praxis/rodrigue/index.html

Selfe, Cynthia, & Richard Selfe. (1994). The politics of the interface: Power and its exercise in electronic contact zones. College Composition and Communication, 45(4), 480–504.

Serafini, Frank. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sheridan, David, Jim Ridolfo, & Anthony Michel. (2012). The available means of persuasion: Mapping a theory and pedagogy of multimodal public rhetoric. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Wysocki, Anne Frances, & Julia Jasken. (2004). What should be an unforgettable face…. Computers and Composition, 21, 29–48.