I teach in a communications department that emphasizes critically-informed digital literacy, social justice, and civic engagement. Many courses in our curriculum ask students to engage in social justice topics through hands-on work with non-profit clients or community partners (e.g. Beautiful Social). However, when I was hired, I struggled with actualizing a community engagement model or conceiving of how I could enact our department’s commitment in my graphic design and visual rhetoric classes. I didn’t have local connections, and I felt I didn’t have the time or training I needed to reach out and initiate partnerships. Many instructors of digital or multimodal composition may be in a similar situation: we want to do real-world, hands-on design advocacy, but in reality it’s not possible or appropriate to directly connect students with the populations who need advocacy. My post describes what I did to create the conditions for design advocacy (or the use of design to promote or perform social justice initiatives) without authentic client or community relationships to ground the course.

For my upper-level undergraduate course in graphic design, I created a pair of linked assignments that prompted students to first visually communicate a social problem in illustrations (Project 1) and then in a series of advocacy posters (Project 2). I structured the first project as a hypothetical commissioned piece, with the assignment acting as a design brief. Students chose a recent article about a social problem and created magazine illustrations to accompany the article. I asked them to imagine their work fitting into the context of the magazine and align their sense of audience (as much as possible) with the article’s audience and the magazine’s target demographic. Focusing on the same issue they researched and illustrated for Project 1, students created two or three advocacy posters for Project 2. The assignments encouraged students to invest themselves in a topic by assuming multiple audience perspectives, first working as illustrators and then as advocators. Students had to negotiate these different genres and purposes and understand how the change in context affected their sense of audience. After two semesters of teaching these linked assignments, I’d like to highlight some of the beneficial outcomes as well as some of the challenges. In my discussion, I focus on Project 2, the poster assignment, but above I link to both assignment pages for context.

Posters and advocacy

Posters are a powerful medium of visual expression, especially when serving purposes of advocacy and consciousness-raising. As physical objects, they take up public space, arrest the eye, and demand the attention of passersby. Circulated and hashtagged on social media, posters carry their messages far beyond the intended or local audience and become important tools for voicing support, raising awareness, and building communities of resistance. Socially-engaged posters, in short, are “dissent made visible,” according to design scholar Elizabeth Resnick (2013). They are a way to resist power. When we see an injustice unfolding or a harmful agenda being carried out, we can use posters to point and say “look at this—it is happening and it is real—don’t ignore it.” We can use posters to show solidarity and enact activism, approaching design “as an avenue for fueling social justice work” (Jiang and Tham, 2019). So many successful activist campaigns throughout history, from Silence=Death to Occupy Wall Street to We the People, use design to carry out social justice initiatives, and these posters now act as documentary evidence of a cultural moment.

In introducing the advocacy posters project to my classes, it takes a bit of work to get students to see posters in this light. Some think of posters as an old-fashioned or bureaucratic genre: movie posters encased in glass outside the theater, signage posted in or around public transportation, or flyers splashed around campus to promote events. In my experience, students often view graphic design in general as a superficial practice—as decoration added on top of the real message, like icing on a cake.

I assign a few resources to illuminate the history of the poster as an activist genre and to start a discussion about how poster design (and all design) can have real effects on the world. We look at the website associated with Resnick’s poster exhibition, Graphic Advocacy, which convincingly shows that posters can be “a medium for social change,” as she writes in her introduction. This short documentary about Emory Douglas and his work for the Black Panther Party during the civil rights movement serves as a concrete example of posters used as weapons against oppression. Combined with excerpts from Compose Design Advocate by Anne Wysocki and Dennis Lynch, students encounter the idea that “Composing and designing [are]actions that DO something in and to the world” (Wysocki and Lynch, 2013, p. 284). The authors write that advocacy—like all communication—is an attempt to shape the world: “effective advocacy requires figuring out how to design the futures we seek” (Wysocki and Lynch, 2013, pp. 283-4). In class, we discuss excerpts from design historian Ellen Lupton’s book How Posters Work, focusing on the 14 design techniques that she identifies in a range of posters, many of which are examples of design advocacy. We review the various purposes of advocacy posters and look at lots of examples: those that aim to inform and educate, to unsettle or shock, to stir emotion and call to action, to change mindsets or behaviors, to join a movement and work to realize a different future.

Student posters

This semester, students in my COM 473: Advanced Design course pursued many of these goals in their own posters. Their work shows how color, shape, image, typography, and layout come together to make an argument. However, they also expose opportunities for improving my approach to the assignment.

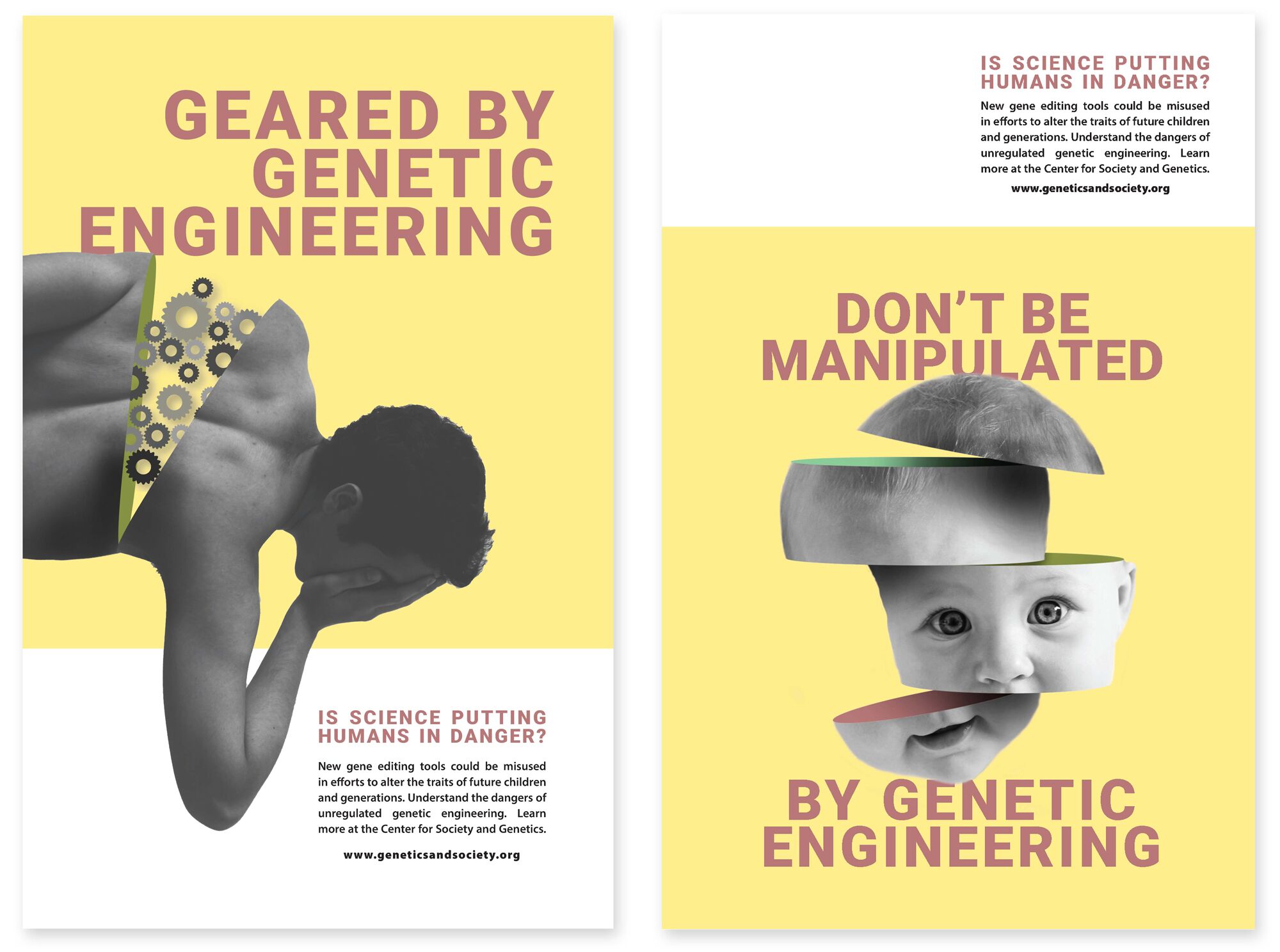

In student explanations of their goals and choices, the most common purpose students pursued in their posters was raising awareness of a problem or issue. Closely connected to that, many students wanted to inform or educate the audience–or inspire them to self-educate by going out and learning more. As Kellie wrote: “These posters encourage the viewer to not stand by in ignorance; instead it poses a call-to-action for them to learn more about the regulations of genetic engineering or lack thereof.” Kellie entrusted her audience to go beyond just reading the headline and to get close to the poster and read the questions and startling facts. She intended the large graphics “to instill some form of fear” and to be the focal point that would draw the audience in, making them feel uneasy but also sparking their curiosity. Peyton, in her posters on the topic of toxic chemicals in plastic products, wanted her design to raise awareness and “make people question” their choices as consumers. “People need to start educating themselves,” she wrote. Thus, her posters serve as moments of insight for the audience. Since they are more like jumping-off points rather than informational texts (as Kellie’s were), Peyton chose a simple design with big typography combined with a visually interesting photograph.

Other students had a more ambitious goal of using rhetorical strategies that would incite a change in viewers’ behavior. Shannon tackled the topic of the vaping trend and rising rates of teen nicotine addiction. Her magazine article in Project 1 focused on the JUUL e-cigarette, so she stayed with that focus and adapted her illustrations for these posters. Writing about her target audience of misinformed youth, Shannon wrote: “I [used]a fear-based tactic in order to educate and encourage change. The average teenager doesn’t realize how dangerous vaping is.” Her posters draw on the well-known color palette from the Truth anti-teen-smoking campaign and use bold graphics and typography. Her second poster addresses the audience directly, stating “A nicotine addiction is not your future.” Madison also sought to change audience behavior. In her poster designs, she addressed the topic of fast fashion and textile waste, writing in her project statement that “this poster is designed to shock and intrigue viewers, prompting shoppers to consider their own shopping habits.”

The challenges and benefits of design advocacy

I conclude with a few recommendations for anyone wanting to teach advocacy posters in their own classes. In our current technological moment, posters are likely to move from physical or offline media to digital or online media with ease. Students could research how posters for the Women’s March, for example, live material lives on the streets and then later rematerialize in blog posts, social media feeds, and digital archives. Using relevant hashtags, linking to websites, or using a QR code in the poster, then, is an important step in bridging the gap. In Peyton’s poster, for example, the use of a hashtag or QR code would have, from the outset, prepared the design to do advocacy work in multiple media.

One challenge I’ve encountered when asking students to do design advocacy work is the “playing it safe” phenomenon, in which students hesitate to choose taboo or inflammatory topics and likewise shy away from truly shocking or aggressive design. Showing more examples of controversial graphic design in class would have pushed students to take more risks, but I need to be cautious about showing traumatic or triggering content in class as well as asymmetrical power relations concerning politically volatile issues. Critical pedagogy (Freire, 2014) and contact zone pedagogy (Annas, 1987; Pratt, 2002) provide a foundation for encouraging rhetorical risk-taking in service of addressing power dynamics through poster design.

The major benefit of the assignment, when the framework of community engagement or a client brief is not available, is that it provides a means of participating in social change—to actually resist power rather than act as a spectator. The student must not only see a problem but also identify where she can intervene. She must take a stand and assume a purpose outside the constraints of a client brief. For students, advocacy posters cultivate empathy and create opportunities to give a voice to issues that matter to them and to the community they care about.

References

Annas, P.J. “Silences: Feminist Language Research and the Teaching of Writing.” Teaching Writing: Pedagogy, Gender, and Equity. Ed. Cynthia L. Caywood and Gillian R. Overing. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987. 3-18.

Dress Code. (2015). Emory Douglas: The Art of The Black Panthers. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/128523144

Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Jiang, J., & Tham, J. (2019, February 5). Multimodal Design and Social Advocacy: Charting Future Directions for Design as an Interdisciplinary Engagement. Retrieved April 13, 2019, from Digital Rhetoric Collaborative: http://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2019/02/05/multimodal-design-social-advocacy/

Lupton, E. (2015). How Posters Work. New York, NY: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Pratt, M. L. (1991). Arts of the Contact Zone. Profession, 33–40. Retrieved from JSTOR.

Resnick, E. (2013). Graphic Advocacy. Retrieved from http://graphicadvocacyposters.org/#/interview-with-elizabeth

Wysocki, A. F., & Lynch, D. A. (2013). Compose, design, advocate: A rhetoric for multimodal communication (1st ed.). Boston: Pearson.