Can technology be racist?

This is a question I ask students to grapple with. Many of my students think that this question is absurd. Technologies cannot be racist, only people can. This is what I hear from many students at the beginning of the term. To these students, enrolled in an undergraduate technical communication class called “Power, Privilege, and Bias in Technology Design,” racism is something that is based on the intent and actions of a few bad or ill-informed individuals, not something encoded and embedded in something as seemingly neutral as technology. This is where we start the term, but it’s not where we end up.

In his pivotal work “Do Artifacts Have Politics?”, Langon Winner cautions us to the devastating potential of disruption of technology “so thoroughly biased in a particular direction that it regularly produces results counted as wonderful breakthroughs by some social interests and crushing setbacks to others” (Winner 1980). This quote exemplifies what I want to attune students too. That yes, technology has the capability to generate positive change and advancements, but it also has the capability to do create harm, especially to groups already facing marginalization or oppression.

In this class, I commit to students that we will critically examine the ways in which technology is designed and how it both disrupts and reinforces existing social structures. We investigate how the design of technologies is shaped by social, political, cultural and material forces. But considering and critiquing injustice in society isn’t enough. In order to truly grapple with these issues, we must attempt to disrupt and intervene in injustice.

My goals are to first complicate students understanding of technology as neutral and then work to intervene through the process of design. At its heart, design advocacy is about action, it is about empathy, and it is about intervention.

Who is centered in user-centered design?

The field of technical communication has a long-standing and intertwined relationship with usability and user-centered design, a systematic approach to designing technologies, systems, products, and services (Redish, 2010). But in the process of user-centered design, not all users are centered equally and marginalized groups can find themselves even further on the margins when it comes to design.

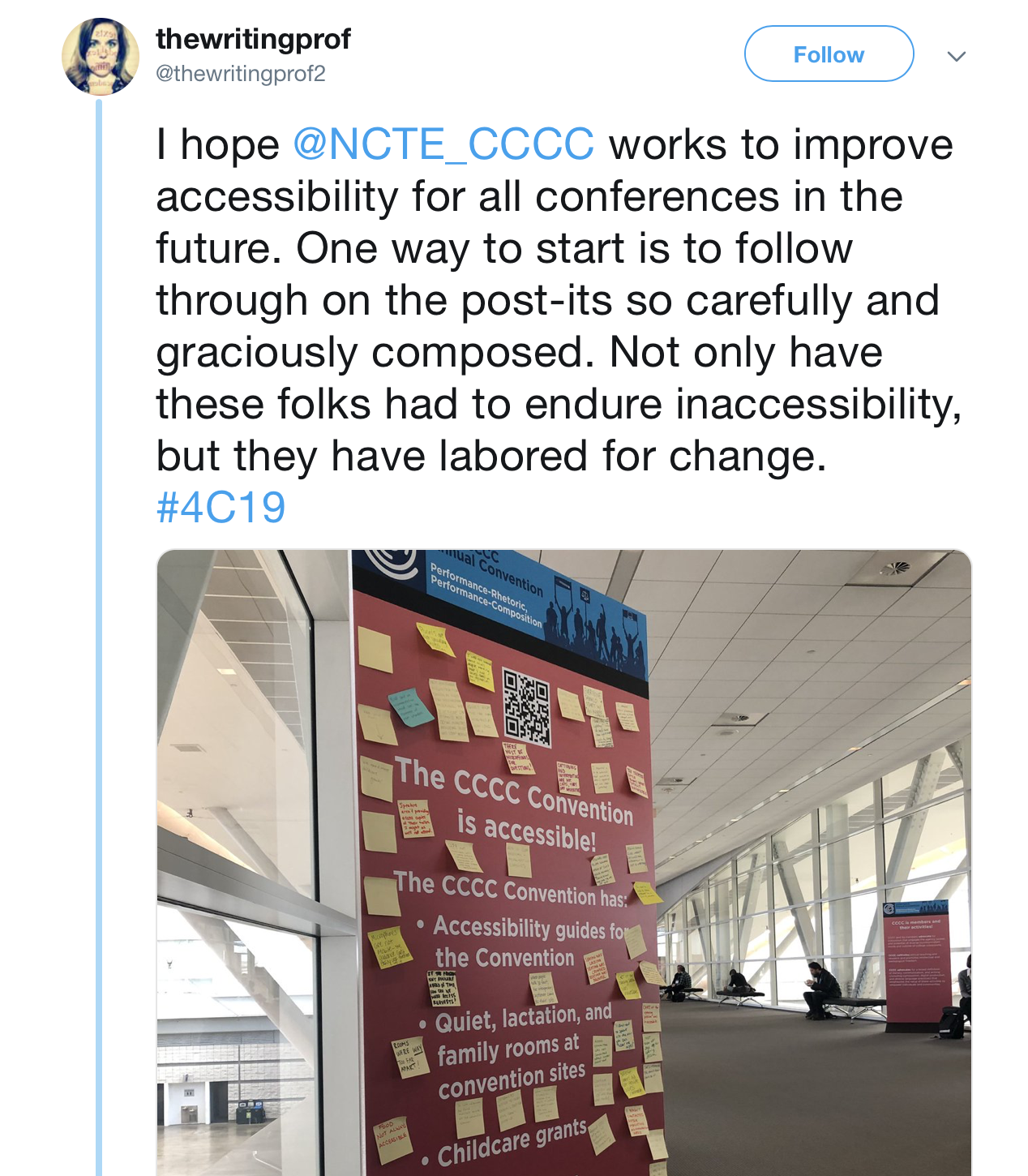

There are ample examples to call upon in class. In the case of race, we discuss the racist soap dispenser, #AirbBNBwhileblack and how the sharing economy reinforces marginalization (Todisco, 2015; Edelman, Luca & Svirsky, 2017). We discuss the problem with algorithmic bias in photo tagging and search (Noble 2018), facial recognition, and digital redlining. When it comes to gender, we can point to the death and danger caused for the disregard of women’s bodies during the initial design of airbags (Criado & Perez, 2019), or the very recent historic all Women Space Walk that had to be canceled at the last minute due to a lack of space suits that could fit women’s bodies. And while strides have been made to design for people with disabilities, there are countless examples all around us: in our browsers, in our communities, on our campuses, at our conferences where accessibility as a design principle is overlooked or insufficient.

Figure 1. Board at 4Cs 2019 conference in Pittsburgh, PA claiming an accessible conference covered with sticky notes pointing out areas for improvement. (Credit: https://twitter.com/thewritingprof2/status/1106576243334483968)

For folks already experiencing marginalization in other aspects of life, we don’t need that much convincing that oppression is baked into technology design. However, if you move around in the world inhabiting privilege, whether that is in the form of a body, a gender, a race, or a set of abilities that are seen as the default (Wachter-Boettcher, 2017) then perhaps you are not used to seeing how the world is designed. When the world is designed for you, its design is rendered invisible.

Hacking Bias

In order to have students go beyond critique and embrace action, I require them to engage in design advocacy and to choose who to center in the design process. The core assignment in this class asks students to go further that just being persuaded by the copious examples that claim the inequities in society that are all around us and are embedded in our technologies. Instead, I ask students to try and see the world otherwise by rendering a different design. The assignment, called Hacking Bias, is a form of design activism enacted in a way that has students attempt to question the status quo and use design to imagine and render the world in an alternate view.

The students work in teams to identify an example of bias in technology, whether it is related to race, gender, disability, or their intersections, and then create a design to address call attention to it or redress it. The choice of the term “hacking” is intentional, (although, slightly alarming to my curriculum committee). I use it to embody the hacker spirit that includes the idea “access to computers—and anything else that might teach you about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total” (Levy, 1984, p. 72). In this way, it provides the person engaging in design to feel empowered beyond typical constraints and, as Turkel (n.d.) states, to encourage “…. a relentless curious tinkering in the face of constraint, censorship or lockdown…” The notion of hacking implies both resistance to the world as it is, but also a sense of play and liberation from existing structures.

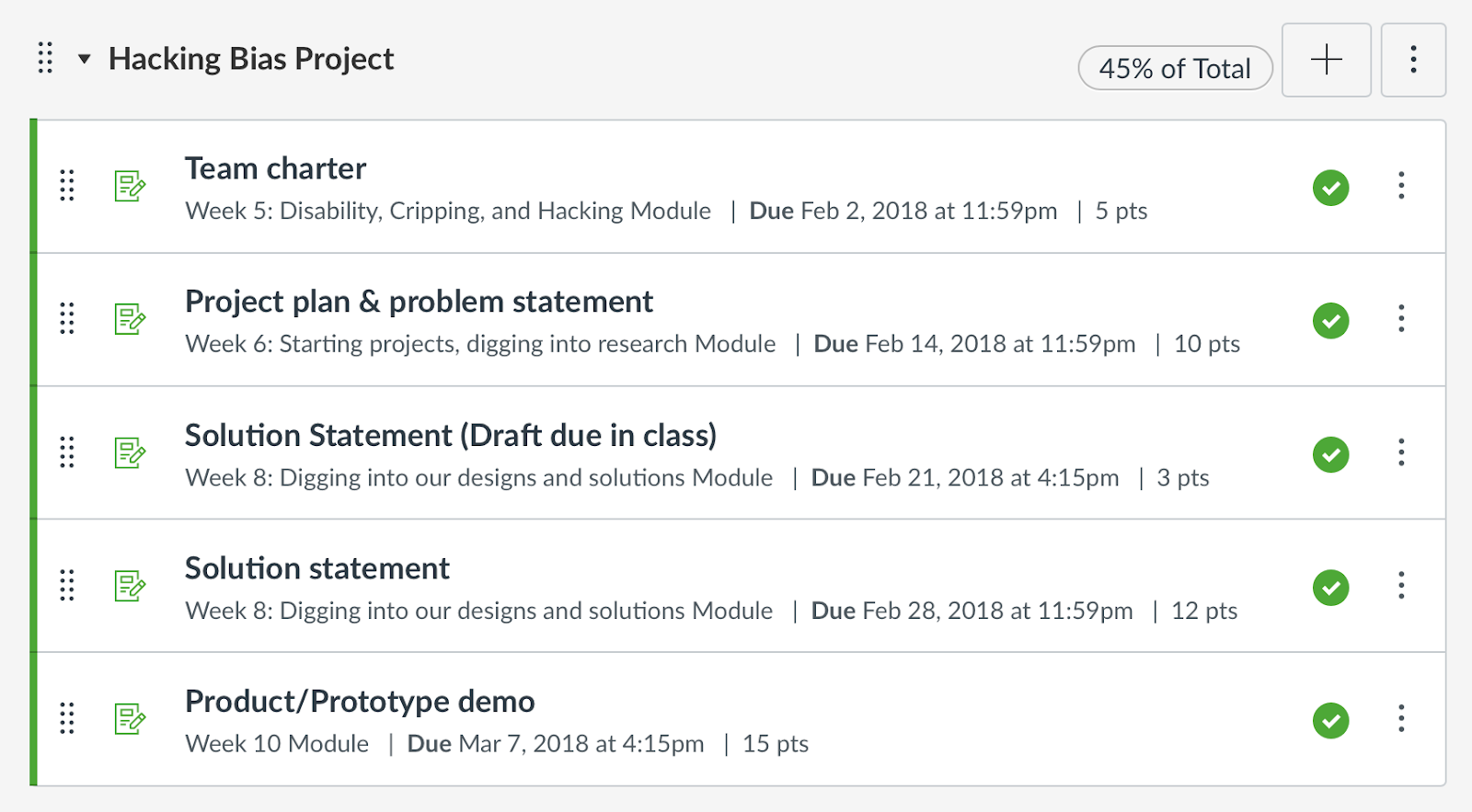

In the first half of the term, we read and examine and critique the examples that are around us. Then, in the second half of the term students brainstorm areas they want to work on and based on these interests I cluster them into teams. I strive to create teams with diverse perspectives, majors, and backgrounds. Then students set to work designing something different, see Figure 2 for an overview of the assignment.

Figure 2. The Hacking Bias Project including deliverables

First, students create a team charter that governs how they will work together, values, goal, and roles. They then create a project plan and problem statement to detail what they plan to do. Next, they follow a user-centered design process where they research the problem to develop empathy and awareness, develop a prototype, get feedback on the prototype and then make iterations and changes based on that feedback. The project culminates in a class product demo where students make a pitch style presentation to discuss the problem they are trying to solve and advocate for a solution.

Efforts and results

I have taught the class twice and each time I am surprised, inspired, and encouraged by the students’ choices of topics and their resulting designs. They have tackled issues ranging from discrimination in the workplace related to gender and disability, food insecurity in underserved communities, sexual harassment, online harassment, online surveillance, housing discrimination, and gender and race privilege, and assistive technologies. From these topics, students have prototyped apps, social media campaigns, events, online services, browser extensions, and assistive technologies, just to name a few.

Beyond the assignment itself, I ask students to create video reflections of their experience (Rose et al., 2016). These reflections allow students to work through their own ideas and thoughts about the project and the course materials as they are experiencing it. At the end of the term, they look back over their previous videos to think about how their topics and thoughts have changed. In these videos, it’s clear how the hacking bias project allowed students to see the choices in design that have intended and unintended consequences and how much effort and negotiation it takes to bring a new idea to life. It is within these moments where I see to see students see the power and responsibility as they grapple with design advocacy.

Strengths and limitations

As I reflect what students have done in the first two iterations of this class and assignment, there are things that have worked well, but there is always room for improvement: for each strength, a corresponding limitation.

The first strength is that students work in diverse teams. This, of course, is challenging, but having to work through together issues that students have experience firsthand: whether it’s sexual harassment, online trolling, or housing discrimination, to name a few, hearing from students how technologies have amplified their own marginalization is a strong way to make a personal connection with the topic. It also highlights students voices and their existing expertise. I am thankful for the institution in which I teach where diversity is one of our greatest strengths. I can imagine a more homogenous group of students might not have as a rich experience, although it would still be important to interrogate the issues regardless of student positionality.

The limitation of students working in teams is that I see that the opportunity to engage in the hands on, nitty gritty, design work, is not distributed equally. This can be due to some students feeling more comfortable doing the designing or when teams delegate pieces of the project for efficiency. Therefore there might be a design that has been developed by a team, but only built by one or two team members. I hope to continue to iterate the course design and require each student to build something to deepen their sense of themselves as designers and design advocates.

The second strength is the requirement to design and create something, to move from analysis to action. When so much of student learning is still assessed through essays and exams, creating and making can feel liberating. Especially when the context is to speculate through prototyping, students can explore ideas without the requirement of full implementation and therefore experiment, fail, try something new.

The limitation is that I see students choose an ambitious topic, but only take small steps in their design implementation. It’s not clear if the modest design choices are about uncertainty about how far they can go or about a fear of taking a risk, but at times I wish for bolder choices. I continue to think about how I can encourage experimentation and risk in these assignments.

Conclusion

Asking students to explicitly engage in design that addresses bias casts them as active participants in design advocacy rather than merely noticing and critiquing. Asking students to center users who are either overlooked or already marginalized can help bring about new outcomes and opportunities for design. My hope is that as they move on in their careers and as they move into organizations where they are asking to design and make decisions, they can think differently about the default user and how technologies can further marginalize and potentially liberate.

References

Ceriado Perez, C. (2019) Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. Harry N. Abrams.

Edelman, B., Luca, M., & Svirsky, D. (2017). Racial discrimination in the sharing economy: Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2), 1-22.

Levy, S. (1984). Hackers: Heroes of the computer revolution (Vol. 14). Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Redish, J. (2010). Technical communication and usability: Intertwined strands and mutual influences. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(3), 191-201.

Rose, E. J., Sierschynski, J., & Björling, E. A. (2016). Reflecting on reflections: Using video in learning reflection to enhance authenticity. Journal of Interactive Technology & Pedagogy, 9.

Todisco, M. (March 2015). Share and share alike? Considering racial discrimination in the nascent room-sharing economy. Stanford Law Review. Retrieved from https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/online/share-and-share-alike/.

Turkel, W. J. “Hacking” Keywords, Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities.” https://digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org/keywords/hacking/

Wachter-Boettcher, S. (2017). Technically wrong: Sexist apps, biased algorithms, and other threats of toxic tech. WW Norton & Company.

Winner, L. (1980). “Do artifacts have politics?” Daedalus, 109(1),121–36.