Each winter, a layer of snow envelops various cities across the planet. While most view the snow as travel obstructions, a movement on social media has reconceptualized snowfall not only as a traffic concern but rather an indicator of poor urban design. Across Twitter, the hashtag #sneckdown is used by people in the US, as well as other countries, to create a unified public that calls for the expansion of sidewalks and other public areas by documenting sections of the street where accumulated snow is left untouched by moving vehicles. In doing so, a unique community is formed – one that is simultaneously anchored in both physical and digital spaces as well as an opportunity for everyday citizens to participate in local beautification and traffic improvement efforts.

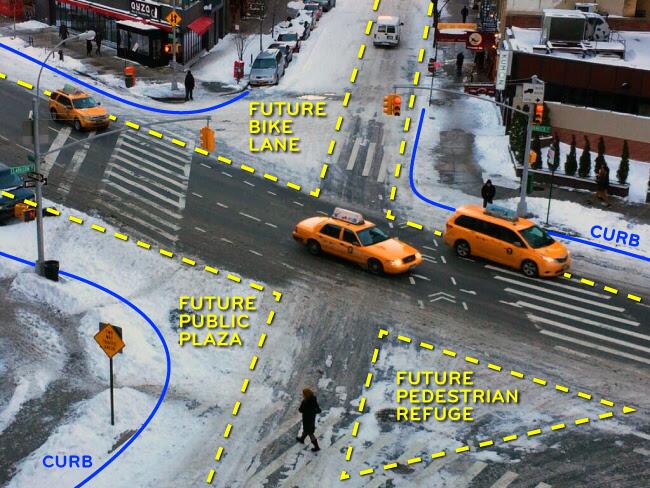

Popularized by a 2011 documentary published on the blog Streetfilms, the word sneckdown is a combination of “snow” and “neckdown,” a term used in urban planning to describe the curb extensions at intersections that reduce the roadway width from curb to curb. There are various advantages to neckdowns, particularly in opening up pedestrian foot traffic. The narrowing of roads around intersections also forces drivers to slow down while turning, thus adding safety benefits for pedestrians as well. Thus, a “sneckdown” is a naturally-manifested neckdown that emerges out of the vehicle traffic occurring after snowstorms. The fallen snow acts as tracing paper, marking the path that cars travel on the road. More importantly, it reveals the parts of the road where cars are not traveling – essentially wasted public spaces where sidewalks could be extended and medians could be built.

#Sneckdown participants walk their local streets, photographing these snowy formations, and post their images alongside the hashtag, thereby contributing data to an ever-growing archive. Though each post may slightly differ in content and style, the hashtag on each post connects individuals as well as their respective regions to one another. The resulting digital community is thus rooted in the different-yet-similar environments that each participant is located within; a Twitter user documenting a sneckdown in Oklahoma City is addressing the same concerns about traffic and pedestrian safety as someone in New York City. #Sneckdown participants therefore not only highlight the traffic-related problems in their local contexts but, through the use of a shared hashtag, also generate awareness on a global scale.

Look how much space cars don’t need. This junction near Canonbury station could, and should, be redesigned. #sneckdown pic.twitter.com/uOHTXMbUWp

— Ben Addy (@BenjaminAddy) February 28, 2018

Church St junction showing how much street space currently is being wasted #sneckdown pic.twitter.com/EGErGQInTH

— space4people ByresRd (@PeopleByresRoad) March 1, 2018

The #sneckdown movement also represents a vital call for the creation of more public spaces in our communities. Sidewalks and streets have always been an integral site for citizens and their everyday lives. Under typical circumstances, sidewalks are what Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Renia Ehrenfeucht consider “sites of socialization and pleasure” (3), connecting neighborhoods and their residents, both metaphorically and literally. However, in times of social unrest, sidewalks double as sites where power dynamics are articulated and played out; “public-space historians have shown that [sidewalks]were also contested sites where rights and access were not guaranteed. Urban streets and sidewalks also have been locations of intervention for reformers and public health advocates” (5). During uprisings like Occupy Wall Street and, more recently, the Hong Kong protests, the sidewalk becomes an aggregator, as “people still take to the streets and feel united with those they find there” (265). Thus, sidewalks function as public spaces that shape (and are shaped by) power relations and their accessibility will always be highly valued in the eyes of the common citizen.

As a digital community, participants in the #sneckdown movement can directly intervene in the power relations of their local neighborhoods. They act as a collective of “citizen ethnographers,” coined by Tatiana Mazali as “users [who]become critical investigators of their own community…narrators of their experiences and broadcasters of their own stories” (292). For #sneckdown participants, there is a sense of pride and duty in bringing awareness to the unused spaces within their locality. Stephan Schmidt and Jeremy Németh argue that “marginal, vacant, under-utilized or abandoned spaces…can be reclaimed as recreational space, community gardens, temporary performance space, or even urban beaches” (455). This idea is expanded upon by Loukaitou-Sideris and Ehrenfeucht, who state that “access to public spaces…is a mechanism by which urban dwellers assert their right to participate in society, and these struggles over the right to use public spaces take different forms” (7). In other words, community members are not only obligated to take back and optimize the places that have been ignored by the state, but they have an inherent right to define the usage of those places. Therefore, it is no surprise that several public sneckdown-centered events have already occurred in various cities. One example involves activist Jon Geeting, who wrote an extensive analysis of sneckdowns in Philadelphia for the blog ThisOldCity.com that went on to be circulated by 1,700 Twitter users and shared by 40,000 Facebook users. The post was published in February 2014, and just one month later, residents, planners, and concerned citizens participated in “Streetfilms, Sneckdowns & the Pedestrian,” an event organized by Geeting and ThisOldCity.com founder Geoff Kees Thompson. Attendees included not only members of the #sneckdown community but also representatives from the city government, such as 1st District Councilman Mark Squilla and the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities’ Andrew Stober. Recently, in 2018, one of the sneckdowns Geeting identified at the intersection of 12th and Morris in South Philadelphia was transformed into a permanent concrete fixture by the city. Ultimately, events such as these demonstrate that those involved in the #sneckdown movement are not just identifying a problem in their community but capable of creating tangible solutions.

Participating in the #sneckdown movement is not as simple as adding a hashtag to the end of a Twitter post; it requires individuals to survey their local landscapes, document their research, and circulate their findings to other concerned community members across the globe. This ethnographer-archiver-analyst disposition is demanding on the individual citizen, but as the recent changes in Philadelphia demonstrate, involvement can lead to actual, physical change, built from the snow up.

Works cited:

Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia, and Renia Ehrenfeucht. Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space. MIT Press, 2012.

Mazali, Tatiana. “Social Media as a New Public Sphere.” Leonardo, vol. 44, no. 3, 2011, pp. 290–291. MIT Press Journals, doi: 10.1162/LEON_a_00195.

Schmidt, Stephan, and Jeremy Németh. “Space, Place and the City: Emerging Research on Public Space Design and Planning.” Journal of Urban Design, vol. 15, no. 4, 2010, pp. 453–457. Taylor and Francis Online, doi: 10.1080/13574809.2010.502331.