Introduction

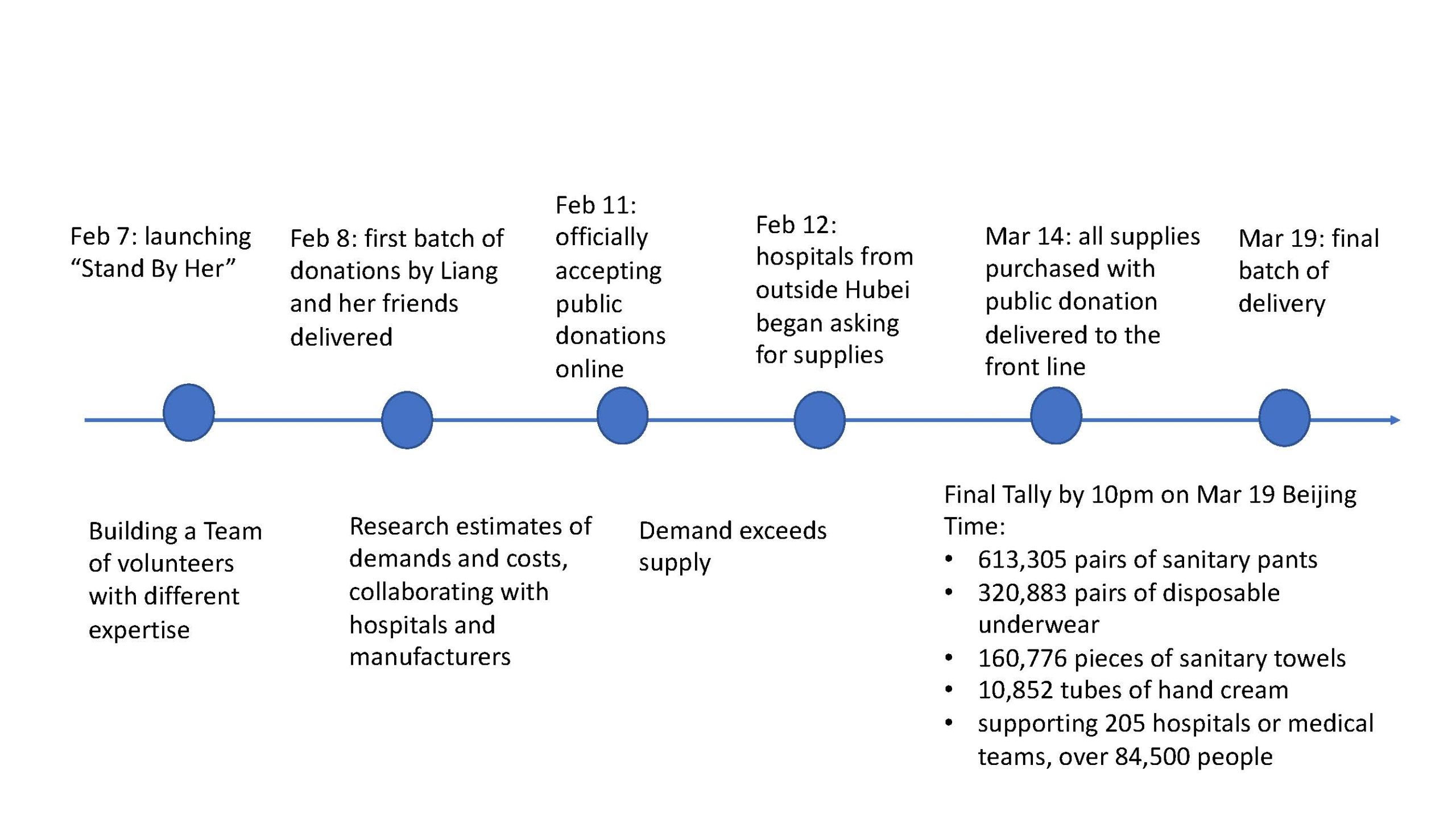

As a response to the fast spread of the novel coronavirus in China, the lockdown quickly implemented in Wuhan on Jan 23 had many ripple effects. Women medical professionals and their needs were especially not heeded even when various medical relief efforts coming from all over China rushed to the epicenter. LIANG Yu (NOTE: I capitalize LIANG here to emphasize it’s her last name. I will use “Liang” later. Her Weibo handle is her Chinese name and English name combined: @粱钰 stacey), is a philanthropist who organized the project “Stand by Her” (姐妹战疫安心行动) to coordinate donation, procurement, and distribution of feminine hygiene products to women medical professionals in the epicenter (see the timeline of the project with highlights in figure 1). While Liang herself is located in Shanghai, hundreds of miles away from the epicenter, she and her team of 91 volunteers from all over China coordinated their efforts completely online to support women medical professionals in Wuhan and other cities in the Hubei province where the outbreak started and was most serious.

Figure 1. A timeline of this project with some significant dates highlighted across 35 days.

Figure 1. A timeline of this project with some significant dates highlighted across 35 days.

In this blog post, I will analyze how this activist project used Weibo (a Twitter-like social network site) to coordinate and amplify their efforts, while combating systemic oppressions caused by the interlocking factors of bureaucratic and sexist policy-based challenges, gender-based discriminations in the broader public discourse on Weibo, and state-sanctioned information control and manipulation. My research responds to the call by Royster and Kirsch (2012) for a globalized view of feminist rhetorical practices, bridging the translation gap Wu (2009) lamented. Using the heuristic “positionality, privilege, power” (Walton, Moore, and Jones, 2019), my analysis will show that Liang was able to establish her and her team’s positionality and employ the advantages of the networked media, performing a feminist rhetoric to empower not only people they supported directly but supporters of women and equal gender rights more broadly.

Stand By Her and Fight With Her

“Stand By Her” exemplified a feminist activism grounded in lived experiences of Chinese women, pushing through a sociopolitical context often quite hostile to women and to grassroots organizing. From Liang’s Weibo posts, I learned a lot about the challenges women medical professionals faced since the outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Without sanitary pads or absorbent sanitary pants when confined in hospitals, they used plastic wraps, adult diapers as substitutes, or they often stayed in their PPE for hours without eating, drinking, or going to the bathroom, or they would run out of underwear and would wear PPE directly, sometimes covered in blood. These problems were directly caused by sexist policies which didn’t consider feminine hygiene products as official “emergency relief supplies.”

To deal with the logistic challenges caused by this sexist policy, Liang and her team worked tirelessly to coordinate their work. Using Weibo, she called for both manufacturers who agreed to donate and hospitals who agreed to accept donations to report on how supplies were transported and distributed to people in need. While such public attention could hold them accountable, it was more important that the policy change so that these products could be labeled as “emergency relief supplies” and enjoy the benefits of “green channels” or officially sanctioned logistic networks by the National Health Commission and the State Post Bureau (see Yao, 2020). She also shared ways for the public to use Weibo to amplify this cause and to write directly to government institutions in charge of epidemic relief to call for this policy change. Unfortunately, by March 21, toward the end of this project, this change of policy still seemed to have failed to be either acknowledged or implemented (for more details on the project, see chronicle of the project: “姐妹战疫安心行动” 纪实, written voluntarily by 6 college students from 3 different institutions, and 6 professionals and published on one contributor’s Weibo, including interviews with Liang Yu and details of the project such as various procedural, institutional, and procedural challenges, how they responded to them, and volunteer highlights).

Liang and her team’s positionality was well established through her Weibo posts to ensure transparency and accountability of the project. Starting on Feb 10, Liang provided daily updates on Weibo on the progress of the project including details such as:

- how much money was collected through the donating platform;

- how much supplies were procured;

- which companies donated how many supplies;

- who the receivers were; and the logistical status update of each batch of donations.

She often posted both textual descriptions of this progress, images of documentation and people delivering and receiving donations, as well as overall tallying infographics. The multimodality of her content offered different kinds of evidence of the legitimacy of the project and supported its transparency.

Liang was also intentional with the discursive and design choices of these content. For example, she explained in an interview that their promotional posters and infographics were intentionally designed with a blue background instead of pink because she wanted to tell everyone that blue could also represent women. She was also adamant in choosing a typeface with straight instead of round lines and not including any cutesy iconography often associated with women. She originally wanted to replace the dot on top in the character 心 for “heart” with a sword but then used a red sanitary pad instead to align with the theme of the project. All of these were meant to illustrate and communicate women’s power (Lai, 2020).

Figure 2. Logo of “Stand By Her” (Image source: Lai, 2020).

Finally, another major challenge faced by this project was the information and discourse manipulation on Weibo which took advantage of a discursive environment and social culture where feminist ideals are still much contested. On Weibo “Stand By Her” was not the only hashtag related to supporting women medical professionals during the epidemic. The Chinese name of the project can be literally translated to “Sisters Combating the Epidemic Free from Worries” which reflected a coalitional effort by banding women together as “sisters” and emphasizing the goals of supporting their epidemic-combating work by removing their “worries” such as the lack of feminine hygiene products. In contrast, other hashtags appeared to serve a similar purpose yet only contributed to an empty epideictic rhetoric of heroic narrative that praised women’s sacrifices without actually revealing and rejecting gender-based oppressions. Here are some examples with my English translation:

Table 1. Comparison of Hashtags.

| No. | Hashtag | English Translation | Number of Reads (usually counted as number of shares) |

| 1 | 姐姐妹妹安心战役 by @粱钰stacey (Liang Yu) | Stand By Her (Sisters Combating the Epidemic Free from Worries) | 480 million |

| 2 | 致敬了不起的她 by Fu Lian and Weibo | Paying Respect to the Amazing Her | 1.9 billion |

| 3 | 致敬战役中的她们 by 一手video | Paying Respect to Them (female) Combating the Epidemic | 8.33 million |

| 4 | 致敬抗疫女性力量 by Sina News | Paying Respect to Women’s Power in Combating the Epidemic | 17.32 million |

| 5 | 谢谢你我的女神 by CCTV net | Thank You My Goddess | 7.88 million |

| 6 | 她们撑起战疫半边天 by People’s Daily | They Support Half of the Sky Combating the Epidemic | 30.46 million |

| 7 | 抗疫一线的妇女节 by Sina News | Women’s Day on the Epidemic Relief Front Line | 94.90 million |

| 8 | 晒晒最美的她 by People’s Daily | Publicizing the Most Beautiful Her | 1.7 billion |

| 9 | 看见她力量 by Sina News | See Her Power | 120 million |

| 10 | 奋斗在战疫里的她 by CCTV net | The Epidemic-Fighting Her | 2.25 million |

| 11 | 战疫一线的巾帼英雄 by CCTV News | The Heroine at the Epidemic Fighting Front Line | 28.63 million |

It’s clear that except for no. 3, all of these hashtag-led discussions were run by State-sanctioned media entities: from Sina Weibo itself, to the newspaper People’s Daily to the Central China Television Station (CCTV), as well as the official State-run women’s rights organization Fu Lian (All-China Women’s Federation), some harnessing more attention than “Stand By Her.” Looking at the hashtags themselves, they often used verbs and verbal phrases such as “paying respect” and “publicizing” or simply emphasizing women’s identity as epidemic fighting warriors and heroines.

These language choices pushed for an empty name recognition and emotionally charging discourse that stopped short at revealing ways that women professionals could really be supported. While it is important to recognize women’s presence in the medical profession, such rhetoric is superficial at best and anti-feminist in its core. I see this as another symptom of the government’s perception of “public reaction as bacteria” that needed to be treated (see Zeng & Liu) by flooding social media with empty rhetoric. Liza Potts (2018) argued that changing hashtags during disaster response could result in “fracturing of the discussion” and causing confusion. Such problems at the minimum can create barriers for people to follow discussion and at the worst, as in this case here, can shift people’s attention away from real meaningful work. Whereas “Stand By Her” served to coordinate the actual efforts to support women medical professionals, these other hashtags had the explicit purpose to manipulate and destabilize the discourse and blackbox it for different ideological purposes, drawing attention away from real activist work.

Conclusion

Since the virus still runs rampant in the U.S. and critiques of inadequate government responses continue, U.S. audiences may be able to resonate and relate to my research here. In particular, unpacking the challenges in this Chinese context reminds us of the sociopolitical and economic nature of digital technologies and platforms. Nevertheless, it is important that analysis from Western perspectives does not only focus on critiquing the problems of Chinese digital and political culture but also recognize how Chinese feminist activists demonstrate their effective digital rhetorical savviness to push back on the oppressions. As a Chinese born scholar living in the U.S., I see it my responsibility to amplify such work. During COVID-19 when Chinese and Asian people at large across the world have experienced much xenophobic discriminations, I want to move away from the victimized portrayal of Chinese people but to highlight their acts of resistance.

The battle against COVID-19 may be a long one, but the battle against gender discrimination and information control is even longer since it’s one that cannot be helped by a vaccine. In this short space I provided a snapshot of the rhetorical success of one project. But there are limitations to my analysis as well given the complexities of Chinese feminist discourses; my naming Liang and her team’s work as feminist rhetorical work doesn’t necessarily mean that she would be labeled as a “feminist” either by herself or others. Without detailed analysis of her full discourse and ethnographic insights on the internal functions of the project, I also wasn’t able to unpack how she gained rhetorical power within her team or how a certain type of fan culture rhetorical phenomenon on Weibo might have contributed to the success of the project. Therefore I hope that my analysis here will also invite people to continue to critically examine Chinese rhetorical feminisms and feminist rhetorics and their complex relationships with digital social networks.

References

Lai, Y.X. (2020, February 22). 一场为女性发起的「战疫」. 人物. https://posts.careerengine.us/p/5e507e9cbec5ba7d33482aa1

Potts, L. (2018). Social media in disaster response: How experience architects can build for participation. Routledge.

Royster, J. J., & Kirsch, G. (2012). Feminist Rhetorical Practices : New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy Studies. Southern Illinois University Press.

姐妹战疫安心行动纪实 (The Chronicle of “Stand By Her” Project). (May 20, 2020). Retrieved from https://card.weibo.com/article/m/show/id/2309404506748722479644?_wb_client_=1

Liang, Y. @粱钰stacey [Weibo account]. Retrieved June 22, 2020 from https://m.weibo.cn/profile/1306934677

Wu, H. (2009). Lost in translation: The modern Chinese conceptualization of rhetoric. College Composition and Communication, 60(4), W87–97.

Yao, X.L. (2020, February 1). 多方联手搭建绿色通道:援助物资是这样运抵抗疫前线的. 澎湃新闻(The Paper). https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_5691009

Zeng, J. Y. & Liu, S-H. (2020, February 20). Epidemic control in China: A conversation with Liu Shao-hua. Made in China Journal. https://madeinchinajournal.com/2020/02/22/epidemic-control-in-china-a-conversation-with-liu-shao-hua/?fbclid=IwAR34Umqh2KxvwiH3u5Z4Ve5CnUU6ou1KQ8HIVXXT5BZP0bx_kQ5NrKD2q-4