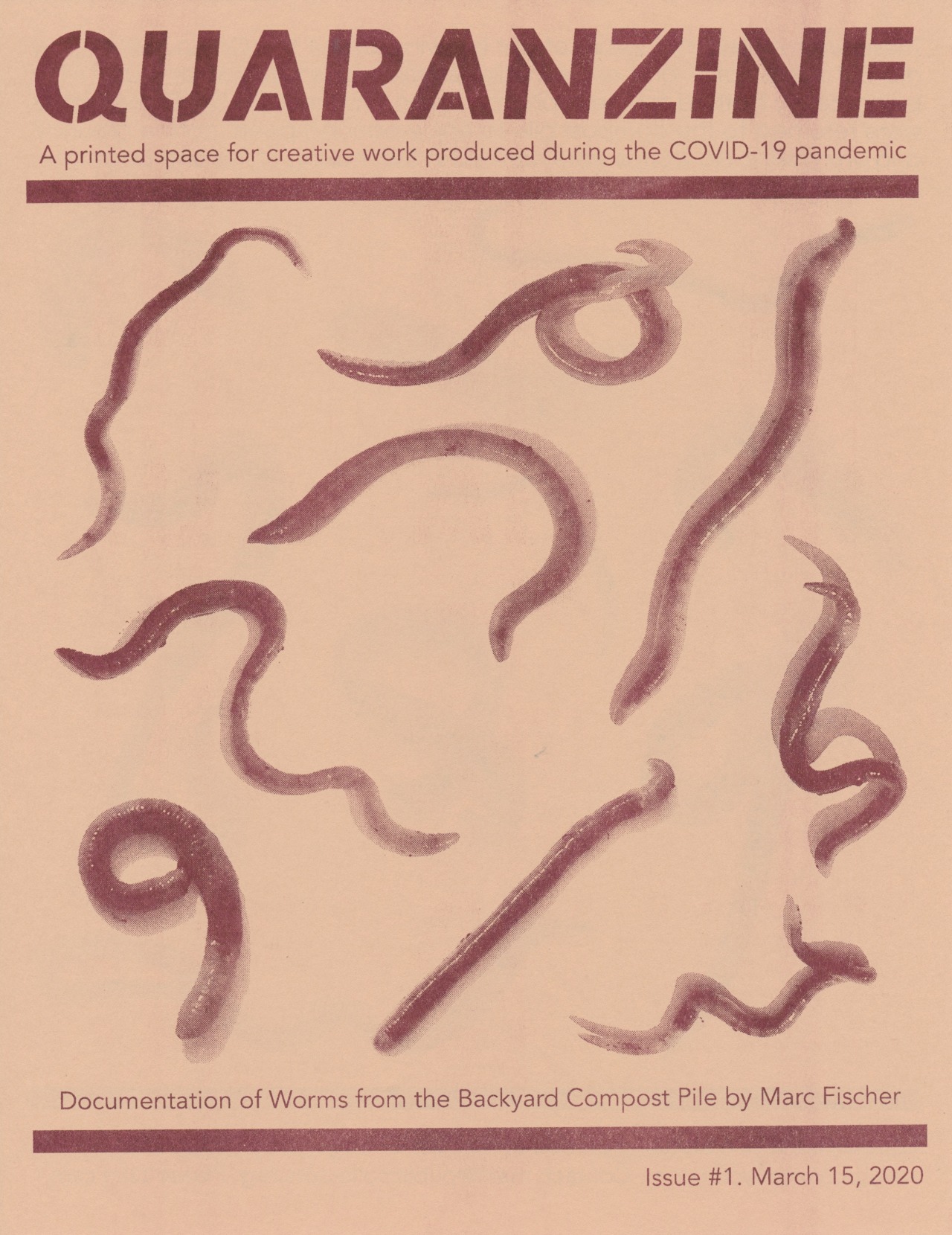

On March 15, as the CDC advised against gatherings of 50 people or more and states like Illinois were banning in-person dining, longtime self-publisher Marc Fischer got to work on his risograph machine, printing 100 copies of the first issue of Quaranzine in his Chicago basement. He was grappling with the gravity of the spreading pandemic and kept busy by photographing and writing about his compost worms. The result — a two-sided, one-page zine — included images of his worms with the text: “These worms have the luxury of not knowing about the Corona virus. They are out there eatin’ and excretin’ like everything is business as usual.”

Fischer would go on to publish 100 issues in 100 days and the rigor quickly required him to tap his social network via “various digital chains” (as he put it to me in an email), recruiting writers, artists, friends, students, and children. These guests, including some who were anonymous, shared essays a variety of work, including: an essay on isolating alone with depression (#2, March 17), a montaged tribute to hand-washing (#11, March 25), instructions on what to do when you get COVID-19 (#14, March 28) and how to build a cat castle (#43, April 26), a plea to keep schools closed (#76, May 30), and “an open letter to the participants in the Black Death Spectacle” (#84, June 6). Fischer plastered issues on neighborhood dumpsters, dropped them in community library boxes, and rolled them to fit through chainlink fences, and added them to his Tumblr account, Public Collectors, tagging each issue “#quaranzine.”

Projects like Fischer’s don’t necessarily tell us anything novel about zines or DIY publishing; however, I open with Quaranzine to show how they amplify what zines already are, or at least can be, in a post-digital mediascape. Indeed, I agree with Rosemary Clark-Parsons (2017) that zines are a digitally networked feminist practice, to the extent that they have “persevere[d], in spite of, but perhaps more accurately because of the meteoric rise of blogging and social media platforms” (558; emphasis in original). I want to further extend Clark-Parsons’s argument here to suggest that the DIY ethos of zines, under the constraints and exigencies of COVID-19, illustrate their rhetorical capacity.

Such capacity might be best understood through Casey Boyle’s concept of rhetoric as posthuman practice; such practice considers how bodies form, accrete, dissolve, and reterritorialize with nonhuman entities, including technologies, politics, cultures — and viruses. Humanity, in this way, is not so much determined by the agency achieved via contemplation or reflection (though we could certainly read quaranzines in this way), but how we compose with and through other bodies and information. For this reason, a posthuman practice foregrounds ethics to consider the consequences certain formations have within a changing network or ecology. At a time when traditional humanism would frame agency as individualized, posthumanism shifts our focus away from what rhetors say to what distributed bodies do and how they are always in-formation.

It might seem odd to frame zines through a digital or posthuman lens, especially when many scholars and zinesters have defined their authenticity via print. But their adaptability as an alternative media can also be gauged via the shifting progressive exigencies of DIY culture — whether it is the dis/utopian concerns of hackers, hippies, and makers (i.e. sci-fi zines and Whole Earth Catalog), the class consciousness of anarchism and punk rock (i.e. Punk and Maximumrocknroll), or the identity politics of feminist, queer, and anti-racist movements (i.e. Riot Grrrl). As different bodies have encountered technologies of DIY culture, they have in-formed and been informed by other encounters with other bodies, requiring zine makers to consider “which practices are best fitting for developing sensibilities for an ecology of relations” (14). Quaranzines are but another ethical practice in the ongoing ontology of DIY culture.

Consider All We Have Is Each Other: A Guide to Creating Fabric Masks, one of the many quaranzines covered in this Hyperallergic article that has also been acquired by the Barnard Zine Library. In it, creators Yessi and N share detailed instructions and patterns for sewing masks in both web and print-ready formats, situated in a wider ecology of contingent activism: “if you feel ENTHUSIASTIC and MOTIVATED by the end of this,” they write, “you are invited to create masks based on your personal and collective needs, capacity and interests.”

Aside from the thousands of posts tagged “#quaranzine,” one Instagram account, @the_quaranzine, became a zine of zines: “a collaborative, virtual zine documenting life and thoughts during COVID-19,” ultimately sharing posts from a variety of interested users who DM’d submissions. Similarly on Twitter, @zinesinthedark still retweets zines while soliciting physical copies for future exhibition.

The ethics of fusing these handcrafted and digital bodies has particular currency for scholars of rhetoric and composition. For example, they lead to what Andrew Peck and Katie Day Good (2020) call a vernacular rhetorical strategy, a process that is “potentially empowering for contemporary social movements because it draws on both memetic practices and material-textual traditions, which, in turn, help users cultivate a sense of vernacular authority” (627) — an authority that has become increasingly valuable at a time when public voice necessitates assemblage with corporate and professional bodies. Quaranzine’s handwritten drawings, comics, and inscriptions were tweaked in Photoshop and/or InDesign and are archived on Tumblr (owned by Verizon); “All We Have” is stored on Google Drive; @the_quarazine and @zinesinthedark offer a range of socially-conscious material through their posts — a single-panel comic satirizing mask denialists, a carousel post on self-care, anti-racist drawings of George Floyd — that are stored and shared on Facebook-owned Instagram.

The rapid assemblage of these zines (and the deterritorialization of projects like Fischer’s Quaranzine and @the_quarazine) are an important reminder that whether born digitally or in-print, the afterlife of zines are just as important as their exigences, as they document an ethical perspective that institutional public rhetorics tend to erase or obscure, yet whose infrastructure is often required. As Fischer put it to me in an e-mail:

“[Quaranzine] felt like a very fast, highly condensed version of what I’ve done for about 20 years. The mix of very formal, and quite informal is typical for me.”

Quaranzines, like zines more generally, are rich sites for understanding the evolving, complicated, strategic ethics of social movements and their grassroots or DIY-infused approaches to public rhetoric, however mixed their tools and approaches might be.

Works Cited

Boyle, Casey. Rhetoric as a Posthuman Practice. Ohio State University Press, 2018.

Cheung, Ysabelle. “Enter the ‘Quaranzine’: Zines That Boost Resistance, Mutual Aid, and Self-Care.” Hyperallergic, April 2020, hyperallergic.com/560443/enter-the-quaranzine-zines-that-boost-resistance-mutual-aid-and-self-care.

Clark-Parsons, Rosemary. “Feminist Ephemera in a Digital World: Theorizing Zines as Networked Feminist Practice.” Communication, Culture & Critique, vol. 10, no. 4, 2017, pp. 557–73. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/cccr.12172.

Fischer, Marc. “Re: Quaranzine.” Received by Jason Luther. 3 July 2020.

—. Public Collectors, publiccollectors.tumblr.com. Accessed 6 July 2020.

Peck, Andrew, and Katie Day Good. “When Paper Goes Viral: Handmade Signs as Vernacular Materiality in Digital Space.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 14, no. 0, 0, Jan. 2020, p. 23.

@the_quaranzine. “The Quaranzine.” Instagram, 2020, instagram.com/the_quaranzine.

Yessi, and N. All We Have Is Each Other: A Guide To Creating Fabric Masks. 4 Apr. 2020, drive.google.com/drive/folders/1DAkx_mR2eSs64sGLtBBJ9Hi0oaeuHUVa.

@zinesinthedark. “Zinesindarktimes.” Twitter, 2020, twitter.com/zinesinthedark.