In the early days of the pandemic, fear and uncertainty were felt across many sectors. The material impact to healthcare, income, and educational opportunities differed depending on privilege, but empathy gaps were perhaps more easily traversed because of a basis in collective awareness and experience. Therein lies the threat when we emerge on the other side of this pandemic. We need to tackle the truly difficult work of empathy—traversing wide gaps in experience that stem from inequity. Narrowing those gaps in education will require institutional change, but educators on-the-ground plant the seeds.

My goal here is to begin explicating for compositionists how some theoretical threads of the discipline have prepared practitioners for this era and the equally distressing times to follow. Through this examination, I hope to begin getting at the “master narratives” (Doe et al., 2017) of teaching composition and providing academic support for writers through empathetic pedagogies.

Doe et al. (2017) explain that “academic activist project[s]” touch upon “master narratives” and “master passions” that shape the profession:

Master passions motivate us and stick with us as we shape our careers and our institutions. Knowing these master passions and the ways they work can help us to do our work more effectively (p. 226).

To propose leading with empathy in the face of mounting pressures towards standardization and students-as-data-points constitutes an activist project because it resists corporatized scalability models for learning.

Reexamining the roots of the profession to inform empathetic approaches to learning strengthens this resistance. Therefore, I believe it is worthwhile to investigate how empathetic pedagogies may be built from rhetorical traditions. Rhetorically empathetic pedagogies may be understood as the interplay of kairotic moments and enthymematic connections to individualized student needs.

(A note about my approach: I recognize the calls to quit ignoring the contributions of BIPOC scholars to rhetorical scholarship, which my focus on Aristotle does not heed. In this post, I have chosen to place white, European traditions in conversation with progressive feminist and antiracist work. My hope is that this strategy may reveal where parts of the Aristotelian tradition lack insight for developing a rhetorical understanding of empathy and where intersectional rhetorics should be substituted for the over-reliance on white European traditions in composition.)

In the Rhetoric, Aristotle considers the enthymeme, along with other syllogisms, a rhetorical device (McBurney, 1936, p. 62), but the premises of enthymemes uniquely invoke audiences for proof and persuasion, requiring of audiences a basis in common understanding rather than acquiescence to logical argument. McBurney explains in “The Place of the Enthymeme in Rhetorical Theory” that “the premises which compose an enthymeme are usually nothing more than the beliefs of the audience which are used as causes and signs to secure the acceptance of other propositions” (p. 58). In the case of education, learners and learning environments constitute the primary audience with other stakeholders connected to the environment through a shared interest in student learning.

The term of persuasion McBurney (1936) uses to characterize enthymemes, “acceptance,” may seem inappropriate for the dynamics of learning environments. Educators aren’t typically thought of as practicing from pedagogies that students need to accept as arguments; rather, educators work from pedagogies that inform practices to support student learning.

However, “acceptance” could be considered an empathetic concept for pedagogical development. Rather than accepting an argument, acceptance from students may mean they recognize how an educator’s practices work compassionately within their lives. Students accept approaches to learning that account for who and where they are.

“Accounting,” in the sense of Aristotelian rhetoric, plays an important logical role in the functioning of enthymemes. McBurney (1936) explains, “The ratio cognoscendi … is a reason for acknowledging the being of a fact; it attempts to supply a reason which will establish the existence of a fact without any effort to explain what has caused it” (p. 56). When considering classroom practices and the theories that guide them, educators do not require justification beyond what research and their professional experience determine will create supportive learning environments. Educators respond to the collective requirement that educational environments be shaped for the intellectual and emotional needs of stakeholders. Unfortunately, it requires effort to convince some stakeholders that accounting for emotional needs supports intellectual ones.

Although many educators unabashedly communicate how the affective dimensions of the profession influence praxis, they often feel pressured to downplay emotional considerations during discussions in which “emotional realities” (Doe et al., 2017, p. 222) matter most: when arguing for resources and material support for their students’ learning environments and when developing, revising, and applying their pedagogies empathetically in their students’ lives.

Foregrounding feminist principles in advocacy projects may help overcome this reticence and, as Doe et al. write, “bring to light the role of affect in effectiveness” (p. 216). The authors argue, “To claim a need to move beyond emotion is to obscure the role of emotion in social change and erase the material processes that give rise to—and are shaped by—emotional realities” (p. 222). For the post-pandemic project of advocating for empathetic approaches to learning, avoiding emotionality for the sake of a supposed rationality could prove harmful, even deadly.

Besides the practical arguments for acknowledging the affective dimensions of learning, the distinction between arguments based on emotion and those based on logic is not so clearly made in classical rhetoric. While Aristotle’s rhetoric is sometimes understood to distinguish logical arguments from emotional ones, McBurney’s (1936) reading of enthymeme as central to Aristotle’s writings calls into question that distinction. Despite seemingly clear demarcations in Aristotle’s system, the central place of enthymeme hints at an analysis that harmonizes with Doe et al. (2017), wherein the authors interrogate the “emotion/rationality and affect/action binaries,” because even “’cool rationality’ is an emotional style,” after all (Berlant as cited in Doe et al., p. 221).

The “material processes” that Doe et al. bring attention to when arguing for the appropriateness of affectively informed advocacy create an opportunity also for reflecting on the utility of kairos for empathetic pedagogies. As Sheridan et al. (2012) explain,

kairos is not only a function of social concerns (such as the beliefs and attitudes of the audience) or of symbolic concerns (such as the linguistic devices that can best articulate with certain beliefs and attitudes), but is also a function of material considerations. (p. 55)

Material concerns imbue learning environments, and acknowledging the ways in which educators’ practices rely on the affordances and constraints of these environments compels critical analysis of how those material concerns impact students.

These two rhetorical principles—enthymeme and kairos—may thus be seen as interoperable concepts for pedagogies and practices finding their home in a rhetorical empathy. Educators may apply them both formatively and interrogatively:

- How do/will these practices work within the lives of my students in this moment?

- What common understandings does/should my pedagogy assume?

- How have I created/will I create opportunities for me to see and for students to see their lives in the learning environments we collectively build?

- What do/should the emotional realities of these learning environments reveal about the availability and utility of material resources?

On-the-ground educators should not be seen as wholly responsible for building and enacting empathetic practices in the post-pandemic era, however. The questions above also may be used to motivate institutional change when scrutinizing policies and commercial education industries that seemingly respond to post-pandemic exigencies but treat students as abstractions to be surveilled and punished.

An incomplete list of initiatives and products that lack empathy includes

- the invasive and dehumanizing proctoring-surveillance industry;

- mandated application of plagiarism software that forces participant data collection;

- reductive “skills-based” rubrics (see Inoue, 2019; Broad, 2003); and

- misplaced hand-wringing about student progress that lacks focus on economic violence and systemic inequities.

As educators know, laboring for students creates benefits for society far beyond classrooms and LMSes when approaches to learning are guided by empathy and compassion. Sheridan et al. (2012) place this perspective in sharp relief by stating, “The composition classroom is one site where society models and reinforces the kind of rhetorical practices it values” (p. 174). Especially as we work towards the post-pandemic era, developing and sustaining empathetic pedagogies should model a more equitable world for all.

References

Broad, B. (2003). What We Really Value: Beyond Rubrics in Teaching and Assessing Writing. Utah State University Press. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/140/

Doe, S., Maisto, M., & Adsit, J. (2019). What works and what counts: Valuing the affective in non-tenure-track advocacy. In S. Kahn, W. B. Lalicker, & A. Lynch-Biniek (Eds.), Contingency, Exploitation, and Solidarity: Labor and Action in English Composition (pp. 213-234). The WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/contingency/

Inoue, A. B. (2019). Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. The WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/labor/

McBurney, J. H. (1936). The place of the enthymeme in rhetorical theory. Speech Monographs, 3(1), 49-74, https://doi.org/10.1080/03637753609374841

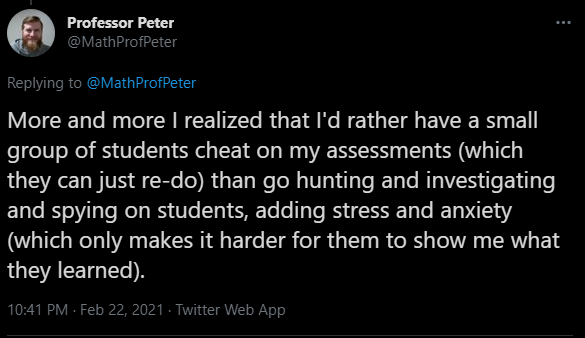

Professor Peter [@MathProfPeter]. (2021, Feb. 22). In my in-person sessions with students today (for my hybrid courses), they were telling me about their experience using proctoring software [Tweet].https://twitter.com/MathProfPeter/status/1364072924550991873?s=20

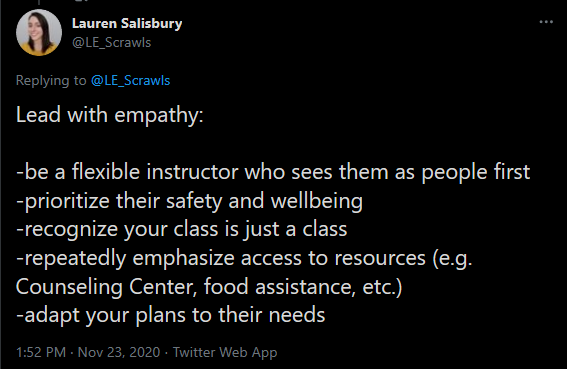

Salisbury, L. [@LE_Scrawls]. (2020, Nov. 23). Your students are having a hard time. A really hard time [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/LE_Scrawls/status/1330961546537742337?s=20 Sheridan, D., Ridolfo, J., & Michel A. J. (2012). The Available Means of Persuasion. Parlor Press.