Let’s just get this out of the way. I love maps. My fascination with maps started young, with a single mother determined to help my brother and me see the country, even on a shoestring budget. We’d pack our van with sleeping bags, a loaf of bread that would always get squashed in the middle no matter where we packed it, and some emergency cash hidden in the leg of the van’s table. As the oldest, I became the navigator, quickly learning the benefits of cartographic literacy as it guaranteed me the front seat for most of the trip. Like Bill Bryson (2015), we lived in Iowa, located in what he called “the biggest plain this side of Jupiter,” but while Bryson remembered childhood vacations for “days and days of unrelenting tedium” required to get somewhere other than Iowa (p. 8), I remember the maps and the infinite possibilities they promised.

I read the atlas with the same intensity that other children of that time approached the Christmas edition of the Sears catalog. Our Rand McNally became dogeared with my future travel plans to the green and wild places of the United States. No one who knew me was surprised when I just kept looking at maps, eventually centering them in my dissertation (Santee, 2010). But it wasn’t until some years later that I began seeing the possibilities of using them in my writing pedagogy.

It probably goes without saying that cartographic technologies and the ways we access maps have changed dramatically since my childhood. Though I still can’t resist a free rest area highway map, most navigation now takes place on our phones, which require minimal engagement as they guide us along our routes. However, the relative ease with which maps can now be made has resulted in their increased use in public communication. Whereas map production was previously an expensive and time-consuming endeavor pursued primarily by professional cartographers using specialized tools and technologies, maps can now be made by nearly anyone with internet access and basic computing skills.

Since Barton and Barton’s (1993) foundational work on maps as ideological communication, writing scholars, primarily in technical writing, have studied maps. However, this spatial mode of communication receives far less attention than visual or sonic media in our multimodal pedagogies. The free mapping technologies that have democratized map-making, though, can be deployed to help students learn to read and critically engage with maps, which is especially important given declining map literacy (Speake & Axon, 2012; Ooms, et al., 2016), even while maps proliferate public discourse.

Maps are complex multimodal documents, and while the specific defining features of map literacy are both understudied and contested, partially because of the complexity of maps and the range of map types (Xie, Reader, & Vacher, 2021), one commonly cited definition is “ability to understand and use maps in daily life, for work and in the community” (Clarke, 2003). Guiding students through the process of creating a map helps them develop map literacy and highlights rhetorical possibilities of multimodal new media composition as maps require the composer to make numerous decisions about content and design. Maps can include significant amounts of alphabetic text, making them appropriate for inclusion in writing courses, but they are not read in a linear fashion, necessitating further decision-making about audience needs and expectations.

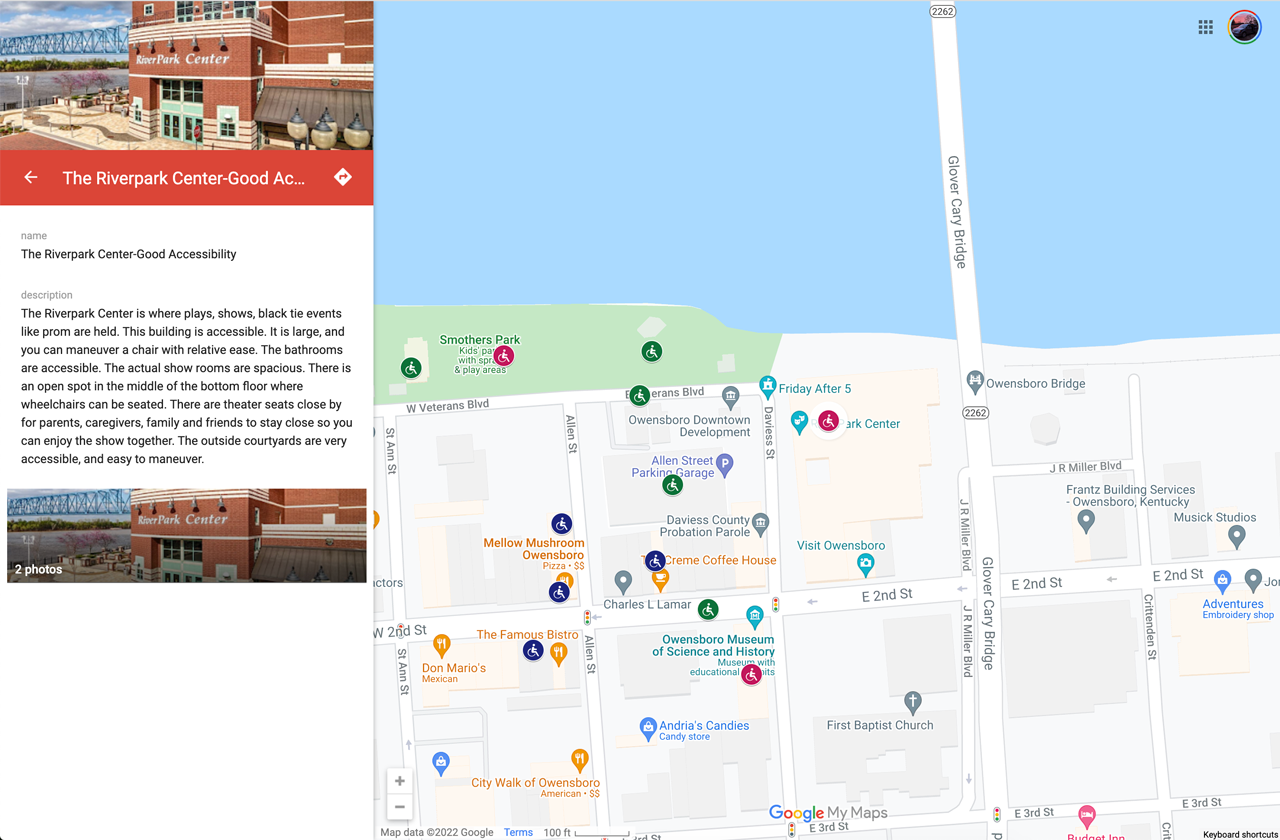

I have used two mapping tools with students to introduce them to map making: Google My Maps and ArcGIS StoryMaps. Both are free web-based tools that provide a significant amount of documentation to help students (and their instructors!) learn to make maps. In the most basic version of a map composition assignment, students can use their local knowledge to curate a set of points with information that could be used by a specific audience for a specific communicative. Google My Maps works well for this purpose given the relatively short time needed to learn the tool and the ease with which students can create a shareable, interactive digital map. In one example below, a student mapped attractions and features in their hometown that were accessible to those using wheelchairs and other mobility devices. This student created the map in response to an official visitor map for the area that failed to give any indication about accessibility, even though the city had worked to create accessible attractions and outdoor spaces, including a wheelchair-accessible playground.

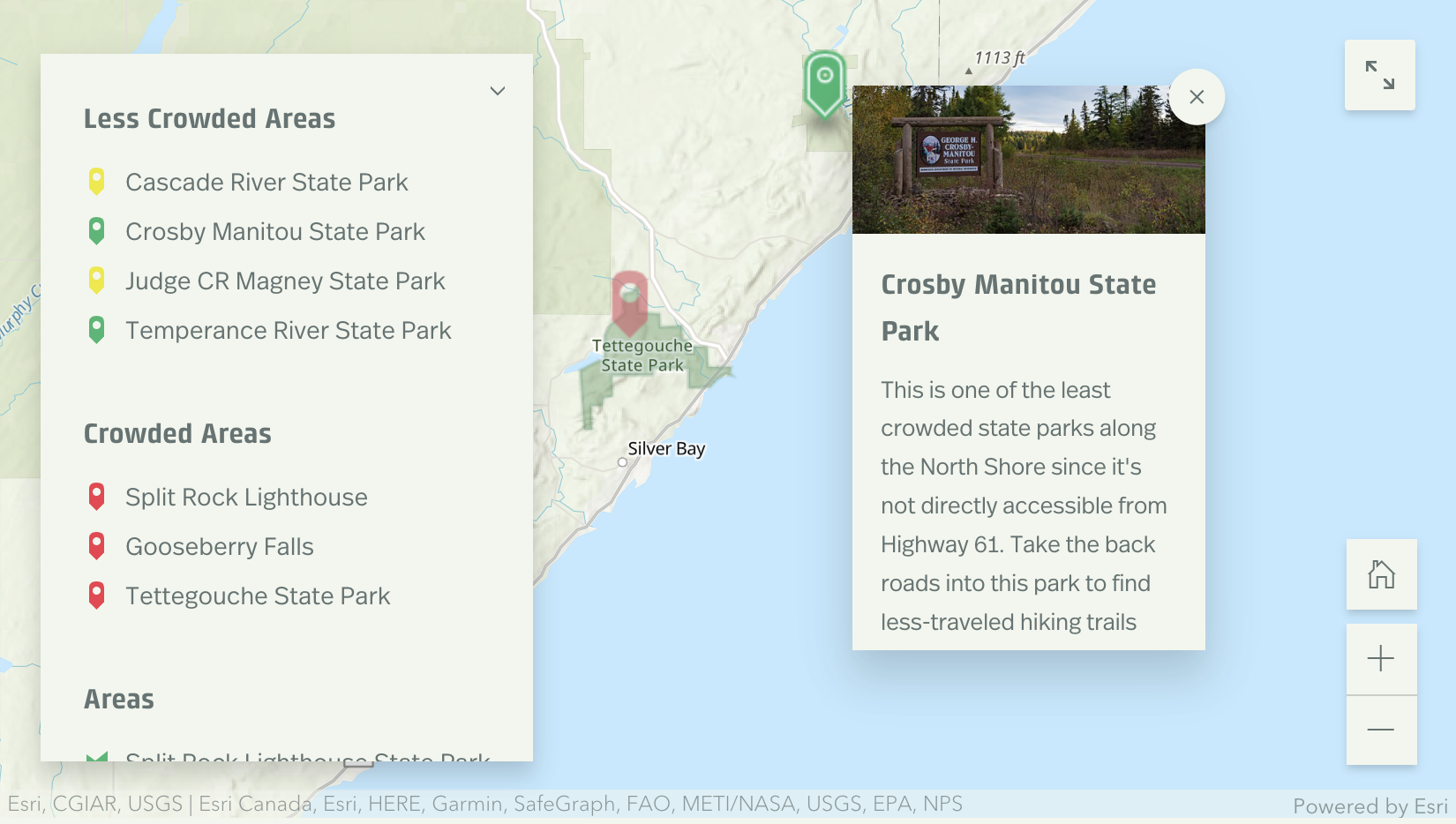

In a more advanced course or for assignments where a map could be used within a larger assignment, ArcGIS StoryMaps provides more flexibility but also more investment to learn to use the tool. Extensive instructional documentation is provided to help students learn the various content and design possibilities within this tool (see Wilber, 2019), and I have found it valuable to devote time to analyzing sample maps created with the tool alongside this documentation to help students make effective rhetorical choices. The example below shows a student’s map of resources for pet owners. This map was created as part of a larger document about ethical pet adoption in an area near the student’s hometown and was intended to provide resources to new pet owners to keep their pet safe and healthy.

At a deeper level and to promote more critical engagement with maps, assignments can be designed to facilitate creation of maps that promote social change or respond to local needs. In an example I created for students (Santee, 2020), the map below was designed to help travelers to a popular tourist area in Northern Minnesota select less-crowded areas to visit during the Covid pandemic.

Students’ projects focused on social change in my classes have included maps that document limitations in local public transportation, argue for improved social services, highlight income-based health care options, and propose locations for mental health services in rural areas.

While my students’ reflections on the maps they create demonstrate a greater understanding of how maps are made and the rhetorical choices that inform what is included and excluded on any given map, one of the bigger questions in my use of cartography assignments in writing classes remains: how do we help students develop rhetorical knowledge that moves from an understanding of the most basic elements of complex media, like interactive digital maps, to critical engagement with those media?

Maps are not the only complex multimodal communication our students will engage with as they progress through their educational and professional journeys. We cannot hope to move them from a lack of awareness about the rhetorical features and functions of a complex genre to nuanced critical understanding in a single assignment. My goal in introducing students to map composition, then, has been modest, focused on creating a foundation of rhetorical appreciation for the choices that go into the creation of a complex document like a map. I hope that this appreciation serves as a base for further study and thoughtful engagement with maps in students’ professional, personal, and civic lives.

The complex, multi-faceted nature of maps means there are nearly limitless possibilities for their integration within our pedagogies, and I hope others will join me in teaching students to make maps both for development of students’ multimodal literacies but also to provide pathways to answering questions about how we move students toward greater critical engagement with complex genres.

References

- Barton, B. F., & Barton, M. S. (1993). Ideology and the map: Toward a postmodern visual design practice. Professional communication: The social perspective, 49-78.

- Bryson, B. (2015). The lost continent: Travels in small-town America. Harper Collins.

- Clarke, D. (2003, August). Are you functionally map literate. In Proceedings of the 21st International Cartographic Conference (ICC) Durban, South Africa (Vol. 10).

- Ooms, K., De Maeyer, P., Dupont, L., Van der Veken, N., Van de Weghe, N., & Verplaetse, S. (2016). Education in cartography: What is the status of young people’s map-reading skills?. Cartography and Geographic Information Science43(2), 134-153

- Santee, J. (2010).Inter-institutional collaboration and the composition of cartographic texts: Mapping the Underground Railroad Bicycle Route (Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University).

- Santee, J. (2020). Protecting yourself and others on the Superior Hiking Trail: Responsible recreation during COVID-19. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/d2fac2061b754e389f23bab056099bde

- Speake, J., & Axon, S. (2012). “I never use ‘maps’ anymore”: Engaging with Sat Nav technologies and the implications for cartographic literacy and spatial awareness. The Cartographic Journal, 49(4), 326-336.

- Wilber, H. (2019, June 16) Planning and outlining your story map: How to set yourself up for success. ESRI ArcGIS Blog, https://www.esri.com/arcgis-blog/products/arcgis-storymaps/sharing-collaboration/planning-and-outlining-your-story-map-how-to-set-yourself-up-for-success/

- Xie, M., Reader, S., & Vacher, H. L. (2021). Rethinking Map Literacy. Springer Nature.