From information scavenger to information creator

You may have seen the rise of new note-taking apps that sell themselves as a kind of “second brain” or “all-in-one workspace.” Their primary function is to store and connect notes of all kinds, from tasks and projects to research and meeting notes. Currently, the most popular are:

- Roam Research

- Notion

- Obsidian

- Craft Docs

These apps have revolutionized the way writers think about information management by allowing deeper connections between blocks of information through bidirectional hyperlinks and fluid interfaces.

Content creators, or writers, no longer store ideas and information in these digital spaces. They use these tools to constantly generate new ideas and content.

Bidirectional linking allows author’s to instantly connect notes across the app with a few keystrokes (double brackets being the most common). For example, if I’m writing a note about note-taking that mentions the canon of invention. I can create a note that references all mentions of invention simply by putting double brackets around invention.

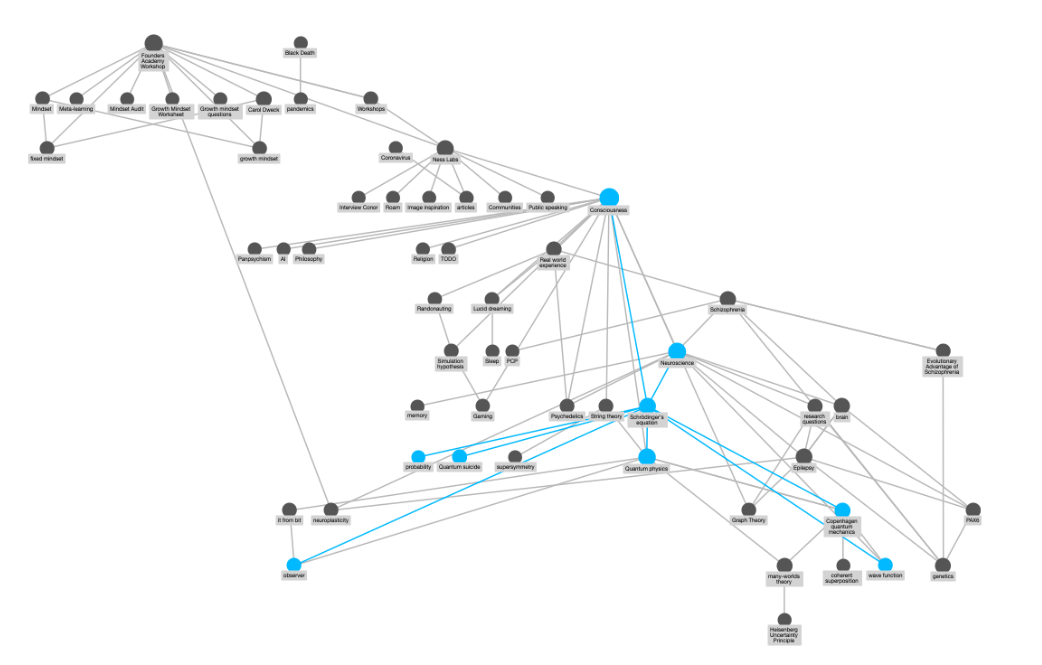

Fluid interfaces allow others to move their ideas and information around in new ways. Think here index cards on steroids. We used to move index cards around to find new connections. Now apps like Roam Research can organize your notes into a graph where writers can explore connections simply by clicking around. Or Craft Docs allows authors to see all the related notes by clicking a toggle.

Both affordances allow writers to leverage associative thinking–a key element to how our brains work when practicing invention in the writing process (Kolb, 2005). Showing these tools in the writing classroom, though, is more than just about coming up with ideas.

For all the great features that apps like Roam Research, Notion, and Craft Docs have to offer the writing classroom, there is one that is easily overlooked—information literacy.

From Scavenger to Creator

According to the Association of College & Research Libraries,

Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

Most students receive little direct instruction in these areas. Yes, we show students how to find sources and evaluate their quality. Maybe we give them some ideas on how to take notes … but we rarely talk about what it takes to create knowledge, not just collect and track ideas.

We train students to gather information like scavengers instead of creating information like scholars.

Integrating these new note-taking apps in the writing classroom can foster an environment that encourages students to develop a deeper understanding of how information and knowledge is created through the writing process.

Though the ACRL has six principles for understanding information literacy, I’m going to focus on number two.

Information creation is a process.

Information is a process, not a thing just out there to be gathered. Sure, creating information involves selecting, organizing, and storing information. But that’s just half the process. To create content, writers must connect, interpret, and share information.

Too often students see information as something you plug and chug into a Word doc. For example, a student might create an outline for a research paper or an argument that they want to make. The teacher requires a certain number of “scholarly sources.” The goal easily becomes about finding a certain number of sources, instead of engaging with new ideas or developing students’ own content.

The student becomes an information scavenger, a writer who collects, but does not create or participate in the information ecology.

Students who think that information is a given will be less likely to revise their information, develop new ideas, or create their own content.

New note-taking apps make this process visible.

Apps like Notion and Roam Research show information creation as a continuous activity, because they encourage the writer to look for new connections. We never know when an old note might connect to a new note, requiring users to carefully construct each note for their future self (or other writers), while also reflecting on how their knowledge database is changing and developing.

Though we can’t force students into a deeper relationship with information, we can spend more time helping students manage information and less time obsessing over grammar or number of citations.

For example, I like to spend at least one class showing students how I manage my own notes. I might show them my most recent note or project and how bidirectional links remind me of connections to previous work. Or how I piece together specific notes to create a first draft of a blog. Then I can have them reflect on their own systems.

Just getting students to reflect on this process is a step in the right direction.

Focus on creating a community database of permanent notes.

Though many of these note-taking apps focus primarily on individual users and many content creators see these as “personal knowledge management systems,” the core technology behind these apps is a wiki … which implies collaborative knowledge management. Having students develop a knowledge management system as a class is one of the best ways to help students experience the information creation process.

For example, I’ve begun having students research the same topic, so that we can build a community of knowledge. Instead of having students just highlight or cut-and-paste notes, I have them write permanent notes in Notion or Roam that incorporate their own thoughts. Based off the Zettlekasten method, this requires students to go beyond writing down information. They must process or engage that information from their own experience. A note is not useful until it’s been integrated into one’s own thinking.

If every student does five notes, you’ll have a hundred useful notes that everyone can use to build new information. Then the writer’s job is to connect these notes in their own way when it comes time to build a paper.

That’s how content creation works online … and that’s how writers become information literate in the classroom.

So how do we teach students to become information creators?

We let them see the information creation process. Though this can be done in many ways, these new “knowledge management systems” provide a high degree of visibility and flexibility. All the other aspects of information literacy often fall into place after this.