Presenters: Dr. Cecilia Shelton (University of Maryland), Dr. Desiree Dighton (East Carolina University), Dr. Ashley Beardsley (Western Illinois University)

When we use the term technical and professional communicator, to whom are we referring? According to the Society of Technical Communication, “Technical communicators research and create information about technical processes or products directed to a targeted audience through various forms of media.” Clearly, this definition would include creators working in social media platforms, but can we include race and ethnicity examples of “technical processes and products?” And if so, does the STC’s definition of a technical communicator already include anyone writing anti-racist activism on popular social platforms such as Twitter and Instagram? The panelists in this session who are blazing more racially and socially just futures of technical and professional communication would respond with a resounding yes. Their research points to ways that the field of TechCom can benefit by engaging the innovative rhetorical moves of activists creating and participating in digital publics.

Cecilia Shelton, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Maryland, launched the panel with #BlackLivesMatter 2.0: The View from the Margins.” Shelton outlined a Black Feminist technical communication methodology that centers Black bodies, histories, desires, and demands at the center of TechCom research and practice. The methodology includes both reclaiming and revising Black histories of TechCom while also developing future-oriented research and pedagogical agendas that systematically integrate Black rhetorical practices as effective ways to do public work. Using a data set of 500 tweets marked by popular hashtags related to the Black Lives Matter movement, Shelton demonstrated how everyday technical communicators leveraged lived racialized experiences as well as cultural arguments to undermine the vicious stereotypes associated with Black bodies. Shelton showcased how Black technical communicators created counterstories of Black identity and representation using the hashtag #iftheygunnedmedown.

Shelton’s slide shows four #iftheygunnedmedown tweets which use juxtaposition to highlight the dissonance between dominant narratives and counterstories of identity and representation.

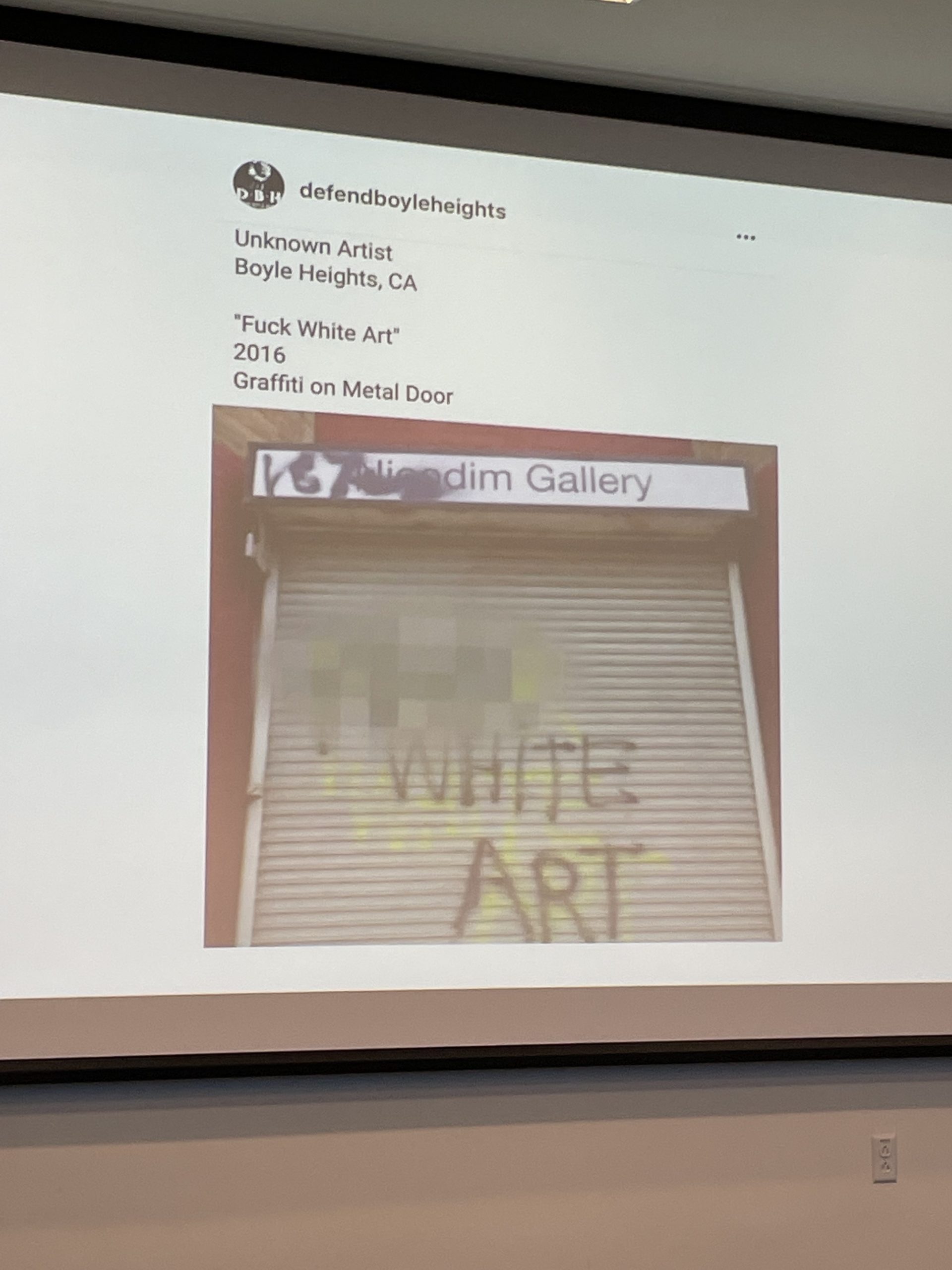

Next, Desiree Dighton, Assistant Professor of Technical Communication at East Carolina University, reiterated the importance of closely examining the in situ practices of rhetorical resistance on Twitter. In the presentation “Encountering Anti-Gentrification Activism’s Uncivil Tongue” Dighton argued that the “civil tongue” of persuasion that we cultivate in our TechCom classrooms assumes a power balance for dialogical engagement; however, these conditions are not typically afforded marginalized activists. Dighton culled over 2.5 mission tweets and their metadata which included the hashtag “gentrification.” An analysis of the most common word pairings revealed how communicators used provocative rhetoric to assemble counter publics to resist gentrification. This large-scale view uncovered national trends; however, Digton also found that the word pairs allowed for closer examination of tweets related to particular locations such a Boyle Heights. Digton explained how assembling select locative data using Carto Map enabled a more human-scale approach to understanding the specificity, materiality, and temporality of everyday digital rhetoric and technical communication.

Ashley Beardsley, Assistant Professor of English Director of the Writing Center Western Illinois University, concluded the presentations with “‘Calling All Bakers, Chefs, Home Bakers & Cooks’: #BakersAgainstRacism and Baking As Digital Social Activist Rhetoric.” Beardsley demonstrated how technical communicators used digital tools to support food activism by announcing their participation in Bakers Against Racism, an initiative that helps bakers organize and participate in selling baked goods to raise funds for anti-racist organizations and initiatives. Taking a McLuhanian view on the centrality of medium to message, Beardsley collected 366 Instagram posts and examined the platform-specific vernaculars that were shared among contributors. Beardsley tracked the frequency of particular icons, such as donut images and anti-racist cakes, as well as the ways that communicators used textual and visual modes (graphics and copy) singularly or in combination to signal participation. In addition, Beardsley’s analysis identified platform-specific citation practices that add to the field’s understanding of how technical communicators acknowledge others’ making, baking, and content creating as well how they establish credibility and context.

During the Q&A period, the presenters responded to the technical difficulties of mining and storing large data sets from social media feeds and the affordances and constraints of tools such as the GW Social Feed Aggregator available to researchers. These conversations quickly turned to ethical concerns in social media research and rejecting harm related to mining, storing, and sharing content out of context. This is particularly salient when writing produced by marginalized people who don’t benefit from the research being conducted becomes data. These concerns will continue to set an agenda for ethics-engaged research as scholars like Shelton, Dighton, and Beardsley expand the possibilities for who and what counts in the study of TechCom. Scholars tacking similar projects might consider the affordances of Shelton and Beardsley’s practices of collecting small(er) data sets and analyzing them via qualitative or “hand” coding; these practice are useful for uncovering nuanced rhetorical moves and relationships among digital images, text, tagging, and hashtagging. In contrast, Dighton’s methods for culling big(er) data sets and using automated text mining with programs such as R package reveals large-scale language-use patterns activists employ around particular topics. As Dighton notes, these data analytics can reveal “intentionally illuminate consequential encounters beyond hashtags” to allow researchers other ways to understand, model, and visualize coordinated social media activism.