Session J.07: Online Social Movements [Saturday, 8:00-9:15am, Feb. 18, 2023, CCCC Chicago]

The panel J.07 Online Social Movement at CCCC 2023 in Chicago looked closely at social media as a platform for activism. As announced in the panel description, attendees (I was one of them) expected “to learn how to resist social media’s algorithmic biases in online social movements, to teach students to analyze online social action movements, and to analyze the profitability of divisiveness in media.” The panel was set up to have two presenters: John Dunn and Heather Lang. Unfortunately, Lang couldn’t make it to the panel. Nevertheless, Dr. John Dunn, Professor of English, who teaches rhetoric, professional writing, and writing studies at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti, Michigan, presented his paper, “Changing the ‘Rules of Hate’: Some Lessons (and Hope) from the New Rhetorics Movements for Reading, Writing, and Teaching Contemporary Public Spheres.”

John Dunn’s Talk

John Dunn begins his talk with reference to a professional journalist Matt Taibbi’s 2019 book Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another. Dunn finds that Taibbi’s book presents an insider’s views on “how economic sides and demands of media have changed the rhetorical moves and appeals that show up in mainstream news coverage.” Dunn thinks it is an opportunity for the instructors like us to help students who look at the world feeling agitated looking at the divisive media saturated world. Therefore, as instructors, we should not only deal with college subjects, credit hours, grades, and academic discourse – but also people’s lives, not just in classroom but as citizens. Considering Taibbi’s book as one of the useful resources, Dunn draws on its second chapter that lists the ten rules of hate that underlie the rhetorical strategies of mainstream media’s news coverage:

Taibbi’s “Tens Rules of Hate” (2019)

- There are only two ideas.

- The two ideas are in permanent conflict.

- Hate people, not institutions.

- Everything’s some else’s fault.

- Nothing is everyone’s fault.

- Root, don’t think.

- No switching teams.

- The other side is literally Hitler.

- In the fight against Hitler, everything is permitted.

- Feel Superior

Fig.1 Text from Dunn’s slide that lists Taibbi’s ten rules of hate that underline media climate.

John continued, as Taibbi argues elsewhere in the book, it has to do with changes in economics of media journalism. So far as competition is out there and social media form other sorts of entertainment or infotainment, journalists have been forced into a series of what we would call rhetorical strategies that are very influential. Taibbi thought it is difficult for a journalist to deviate from such rules. If we follow the news coverage and social media, these things are obvious. Taibbi succinctly boiled down the complexities of media climate to a few recognizable principles. Dunn has used this chapter in his composition class and has observed that students generally find this understandable as they see this in their personal experience.

Why do we care about this? Dunn’s answer is our media climate is likely to remain same for some years or decades and there are consequences of such media climate. Dunn draws upon a now relatively neglected article, “Against Illegeracy: Toward a New Pedagogy of Civic Understanding” by Jeff Smith, published in CCCC in 1994, to suggest how writing instructors interested in political discourse and citizenship can utilize Smith’s still relevant concept of “illegeracy.” Dunn points that the consequence of our media climate characterized by Taibbi can be best explained by Smith’s notion of ”illegeracy” in which citizens and students feel confused being unable to make sense of their cultural situation as they fail to see choices.

Dunn thinks that failure or ability to see choices is important. He often tells his students that rhetoric is an art of seeing choices, recognizing options, and making constructive choices. Even the act of simply realizing that you have a choice whether that is how you write or how you live is empowering. Students may not find that out elsewhere. But taking a writing course — especially a process-based writing course — is going to bring that issue up. Dunn holds that the classical rhetorical tradition of Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian and so on, argues for teaching literacy, writing, and speaking — not necessarily a better writer or a speaker even though there is that opportunity. It is rather geared more to make one a better person or a better citizen by recognizing an agency and choice. And that classical tradition, Dunn thinks, is still quite relevant in our circumstances today.

Advocating one’s political power, Smith was writing in a time when rapid news was high. Dunn highlights a similar concern for an individual’s sense of power in our kind of media environment. When all the agitations happen in social media, and all the wrangles and turmoils that we encounter in our personal relations are enmeshed with political issues, even the sense of getting around and involved for change by voting is very important. Dunn asks: what are our options? What can we do about it? In this climate of confusion based on those ten rules of hate, Dunn locates some options in our field of rhetoric and writing:

Some options

Todd DeStigter (RTE, 2015): via study of argument

David Fleming (CE, 2019) via study of persuasion

Donald Lazere (CCC, 2019): via study of ideology

Skinnell (CCC, 2021): via study of fake news

Fig. 2. Texts from Dunn’s slide that lists some options for reading thorough the divisive media climate.

- First option: DeStigter has written about the curriculum of argument that forms the basis for a lot of K12 education. DeStigter is critical of that in his 2015 article in RTE journal as he points that some of our overemphasis on academic arguments has drawn our and our students’ attention away from the large public sphere. Dunn does not find DeStigter’s critique entirely persuasive but concedes that DeStigter makes an important point. And that has to do with the fact that the education policy can influence what goes on in classroom and curriculum.

- Second option: In his award-winning 2019 piece on persuasion published in College English, Fleming draws upon classical rhetoric to argue that persuasion means all three appeals—ethos, logos, and pathos. Fleming argues that we need to address all aspects of rhetorical canons.

- Third option: Lazere argues that ideological attention is necessary to understand what is going on in the public sphere. One challenge Dunn sees in it is sometimes the discussion of ideology is a bit abstract. Dunn thinks the rhetoric and writing bridges between the abstract and the concrete. So, part of the study of rhetoric is that middle space where patterns of discourse that we use individually relate to bigger picture of our social climate.

- Fourth option: Skinnell has a very fascinating piece on fake news, published in 2021 CCCC journal.

After setting up the background thus, Dunn suggests that there is an earlier period in the field of rhetoric and writing known as New Rhetorics era, in the same fashion as we had New Criticism:

Another Possibility: The Era of “New Rhetorics”(1960s to 1990s +/-)

– Daniel Fogarty, Roots for a New Rhetoric (1959).

– Richard Ohmann, “In Lieu of a New Rhetoric. College English (October 1964).

– Wayne C. Booth, “The Revival of Rhetoric.” PMLA (May 1965).

– Martin Steinman (ed.), New Rhetorics (1967).

– David Fleming, “Rhetorical Revival or Process Revolution? Revisiting the Emergence of Composition-Rhetoric as a Discipline” (2009).

Fig. 3. Texts from Dunn’s slide that lists sources on New Rhetorics.

Dunn continues, the phrase ‘New Rhetorics’ was coined by Daniel Fogarty in his Roots for a New Rhetoric (1959). In that period our field of rhetoric and composition saw a slew of scholarly activities coming into the 60s and onwards. They were looking at some ways to teach writing different form old current traditional rhetoric of grammar book instruction and formal pedagogies. Dunn believes that what happened in the 60s was a sort of awareness. Dunn argues that the takeaway from new rhetorics is still relevant. He sees two useful themes:

- First is from Wayne C. Booth’s PMLA article “Revival of the Rhetoric” which provides a good frame to think about how we serve students or adult citizens. What type of theory, understanding or rational could we offer to adult citizens about what is going on in public sphere, whether that be the turmoil of the 60s or the challenges we face today?

- Second theme for Dunn comes from Richard Ohmann who talks about the need of rhetorics to go beyond the classroom to be a part of larger social understanding. Thus, the sense of rhetoric has a social awareness that is not limited to the words on a page.

Additionally, Dunn finds “world-views” more useful than “ideology”. A text we read is not just words on a page, but it implies various world-views. Dunn argues that classical rhetoricians assumed a greater continuity in terms of culture perhaps because they had a much smaller social climate than we have today. Ancient Greece was the size of the present-day suburb of Chicago. It is important to have the recognition of worldview — whether it is a single text, or a particular author, or subgroups, or discourse communities.

Another text Dunn focuses on from this new rhetoric era is Young, Becker and Pike’s Rhetoric: Discovery & Change (1970) which charts a historiography of the field of rhetoric and writing studies. Dunn finds that the book uses one specific linguistic theory called tagmemics, which is one of the innovations of new rhetorics movements. Tagmemics come out of a relatively an obscure area of linguistics. It originated to look at translation issues in world languages. Much of the work in tagmemic linguistics happened in languages very distant from English, in places like New Guinea, Southeast Asia, South America. A takeaway from this is Tagmemics comes down to an insider view of an organized whole. This is very much a kind of anthropological framework which tries to understudy by getting inside someone else’s head: that’s the challenge of a translator going through an indigenous culture without a written language. The aim of Tagmemics is to understand not just the language pattern but also the social context in which the language operates.

Dunn continues: “We invent our image of the world in the context of using language. That is something students would benefit from recognizing it when they are going through their identity formation—their sense of who they are. It is implicated in the rhetorical theory. In addition to the sense that we [can]see things differently and our different ways has to do with our different ways of using languages. We have an explanation of where that comes from. It comes from the habit around the way we use language, and the ways the segments are experienced.” As a writing program administrator at an access-oriented campus, Dr. Dunn suggests that we probably need to foreground that in terms of what we are making our course about: “We have a good toolbox of strategies for teaching composition. Students who are willing to do the work in a process-oriented composition course get better because they have the teachers like you guys willing to put into effort.” Dunn believes solution lies in rhetorical reading as suggested by Christina Haas and Linda Flower and others. What Dunn does is extending or elaborating their versions of rhetorical reading. Hass and Flower et al. construe rhetorical reading can be done in three ways, which Dunn recommends to us:

- First is to read the content or what part. What’s this text about? What’s the writer’s point or opinion? Majority of people read this way.

- Second one has to do with reading for form or how part. We do some of these in a composition course. We talk about recognizing things like genre conventions. What type of writing or media is this? What are the convention expectations? How do we read this genre successfully? These questions bring us to pay attention things like form, style, rhetorical figures, stance or persona, ethos, logos, pathos.

- Third strategy is the notion of reading for situation—’what change does the writer want the audience to make given the circumstances?’: exigence, audience, and constraints.

Dunn adds a fourth approach:

- For world view (so what/ what’s at stake): “what world view/image of an everyday world does the writer’s patterns of choice imply?” “how does this world view compare with those of rival/competing writers participating in the same public controversy?” & “based on the alternatives available in a given controversy, which world view does a reader choose to accept & why?”

To discuss or interpret worldview, Dunn brings back the notion of tagmemics. Young, Baker and Pike give us heuristics of tagmemic rhetoric that we can use to help students make sense of all. Most famously, they talk about three perspectives that go along with making sense of the theory: seeing things as they were static (particle), seeing things as were dynamic process (wave), and seeing things as a network of relationships or a part of larger network (field). This three-part tagmemic rhetoric argues that understanding of all these aspects is essential to make a sense of the world accurate. One of the things instructors engage in assessment early in the semester is to look at a piece of student writing and track how they use some of these perspectives. Most students can do the particle perspective—focus on something, describe in detailed experience. What they often need help is in describing history or context—how has it changed over time? What are you experiencing is how different than the past? How is it going to be in the future? They also need help in network perspective—network through individual experience to academic activities, through political issues, through the whole meaning of life, and meaning of the universe.

Dunn explains what we find is our own perspectives based around our own priorities. Classical rhetoric talks about the art of making choices—how you make choices makes your priorities. Do I want to buy a piece of artwork which is really expensive? Certain values are at play or are available choices in this case—beauty or money. If I buy it, my priority is beauty; if I don’t buy it, my value of money is greater than beauty. Dunn often tells students that out there are not conflict of just good vs evil, there are also good vs good. The point classical rhetoric makes is a part of one’s identity or character is based upon my habit of making some choices.

Dunn believes there’s an opportunity when working with students to try out some of these implications in a way that the choices they are making in their lives have hierarchy values. And these values relate to who they are, how they see the world, which is essentially what we call education.

Reading for World View: Some Tagmemic Heuristics

Lee Odell, Measuring in Intellectual Process as One Dimension of Growth in Writing (1977):

1. Focus: agent, action, (goal), result (“affected”)

2. Contrast: opposites, actual vs. actual, hypothetical vs. hypothetical

3. Classification: labeling/definition, analogy

4. Sequence: narrative, procedure, cause/effect, Syllogistic progression (cf: F. De’Angelo, 1975: page 45)

5. Physical context

______

6. Hierarchical relation

7. Possibility for change

Fig. 4. Text from Dunn’s slide that outlines some tagmemic heuristics for reading world view.

This is a typology based on Lee Odell’s attempt of measuring changes in intellectual process in the writings (of students). What Odell has done is to take tagmemic theory and look at specific kinds of intellectual processes, strategies, or rhetorical moves. The point Odell makes is these habits of thinking show on the page. Therefore, Dunn suggests, when we are working with student writing, we want to think beyond sentence corrections or paragraphs, and think about what sort of intellectual work the sentences are doing. In particular, Odell points out five to seven categories of strategies. Most important one is the first one—focus. Any writing is about a general subject, but immediately we are making choices about the specific aspect/s of the subject. And of course, by implications, some aspects get ignored or lack the focus. Young, Becker and Pike call them focus and peripheral focus. This will show up in the sentences students write. When we read those sentences, we want to think about not just words and sentences, but also the broader world view. When students write about a subject, they focus on some specific aspect; when instructors give feedback— it can change their focus. Dunn’s point here is that we are shifting from writing to thinking. Another interesting thing for student to ponder is: where does that come from, how do I see things? If we focus on something or several things, we can think about how they relate—an essential feature is contrast. Once we specify contrast, we can classify them, and then attend to sequence, and physical context. According to this tagmemic theory, all these things have to be in play. In fact — strong writing, so to speak — is often the writing that involves all these strategies. What it allows us is to use vocabulary to talk about what we are trying to do in a composition course.

Dunn suggests that we can do it upon the public discourse around us. He gives an example from the Tribune Content Agency (TCA). One of the features TCA offers is opinion columns. A dozen or so opinion columnists of Tribune are divided across political spectrum—left, right, and independent. Dunn gave a couple of examples of opinion pieces (which he handed to session attendees at the beginning) that focused on the purchase of Twitter by Elon Musk at the end of 2021. This generated a fair number of opinions. If one is interested in this genre of opinion column, there is a lot to say about incorporating them into composition curriculum, not just research papers.

Opinion Columns: Rhetoric, Genre, & Appeals

– Richard Fulkerson, “Newsweek ‘My Turn Columns and the Concept of Rhetorical Genre: A Preliminary Study” (1993).

– Roger Gilles, “Richard Weaver Revisited: Rhetoric Left, Right, and Middle” (RR, 1996).

– Douglas Hesse & Barbara Gebhardt, “Nonacademic Publication as Scholarship” (1997).

– Robert Root, Working at Writing: Columnists and Critics Composing (1991).

– Robert Scott & James Klumpp, “A Dear Searcher into Comparisons: The Rhetoric of Ellen Goodman” (QJS, 1984).

– Gregory Shaffer, “Trespassers No More: Students as Columnists” (EJ, 2015).

Fig. 5. Text of Dunn’s slide listing the literature that deal with the genre of opinion columns.

After touching briefly on these sources, Dunn proceedes to discuss the two opinion pieces on Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter. That purchase raised strong arguments–What’s going to happen with Twitter? What is Musk going to do?—on both left (liberal) and right (conservative).

His students highlighted or marked some of the points in the texts that represent these intellectual strategies and tried to see if these fit together. They were trying to understand the world-views that these authors are sharing. They used tagmemic strategies to think about how the authors are doing it. Dunn usually asks his students read these texts and think in terms of intellectual process. Dunn points that readers can see two writers—Reich (Liberal) and Marsden (Conservative)—start out with the same subject: the purchase of Twitter by Elon Musk, and they go into different directions. Dunn asks, how do we understand that and the nature of worldview that is implied in each of their pieces? Based on the highlighted and marked sections in both articles, Dunn shows how they tried to bring that together in a sort of a systematic understanding.

A Tagmemic Analysis of World Views

Particle: appearance (via focus, contrast, & classification)

Particle: appearance (via focus, contrast, & classification)

Wave: prediction of change (via cause and possibility)

Liberal/Reich

/economic system\

– workers vs management

– old workers

=> new workers

new workers

management

new workers

\

Twitter’s future

Conservative/Marsden

/political system\

– censorship vs free speech

– social media vs policy

Policy

social media

social media

\

Republican’s future

Fig. 6. Dunn’s slide with an analysis of Reich’s and Marsden’s articles.

Dunn continues: How the world works? What can we anticipate from it? We can see that further from the field perspective, there is a sense of preference. Reich, the author of “Musk’s Humongous Mistake,” prefers new workers over the management. He basically says Musk is struggling because he is not valuing his workers who made Twitter what it is. Therefore, it is more important than the traditional management style that he might have used elsewhere his industrial empire. On the other side, Marsden’s “Republican Policy Failure Is Harming Free Speech and Their Own Chances” prefers policy over social media. Marsden argues that Republicans are wasting their time debating about Twitter and complaining about it. Dunn asks, how do both authors try to predict how things are going to change? In both cases, we see negative predictions.

Dunn believes that this sort of perspective is implied in the rhetorical moves happening on the page. And therefore, our goal is to alert the students with the questions like: So what? Who cares? What does it lead to? Dunn adds that it leads to a way to help students decide how to choose things and decide how they are making wrong choices of things like politics.

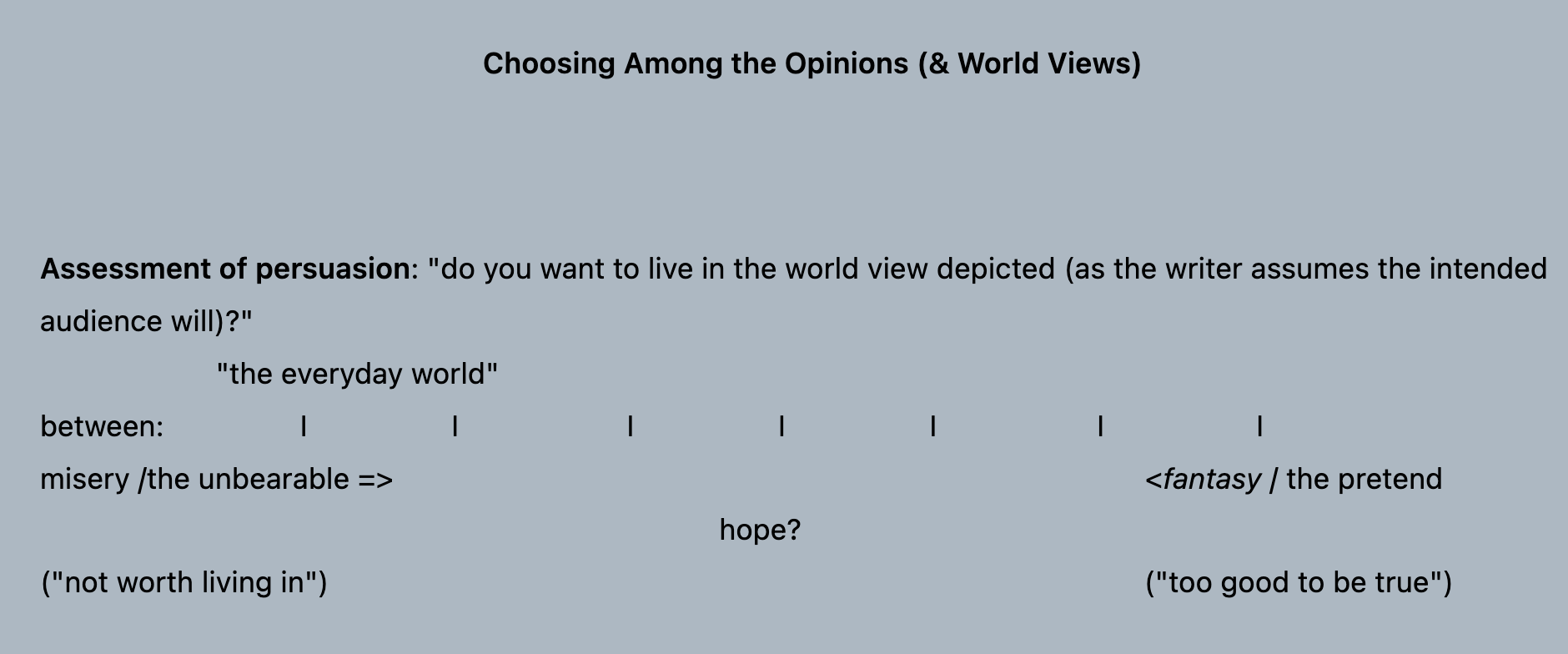

Dunn suggests that when we are persuasive, deciding on what we agree or disagree with, we are depending not only on the arguments in terms of claims and support, but we are also, in fact, influenced by the broader notion of worldview. Dunn thinks the best form of assessing persuasion engages the question: do you want to live in a worldview depicted in a particular piece which author or writer of the piece assumes the intended audience does? This is how people identify themselves. For instance, if you are conservative, you may want to live in the worldview of Marsden’s, or if you are liberal — in Reich’s. We need to decide based on not just texts, but also on our perspective. Where do Reich’s and Marsden’s pieces fall? In everyday world, they fall between two extremes. One extreme is misery, a world in that way is not livable and one doesn’t want to be a part of it; they are not persuaded by it. On the other end of the spectrum on the right side, it is too stupid to be true. Dunn asks, how does it work? He says, ultimately, what instructors and what students decide is suggesting that middle which Dunn terms the “everyday world.”

Fig. 7. Dunn’s slide showing the two extremes of the world views.

Dunn finds hope in the middle ground of “everyday world” which can keep us from the sense of misery. He points that sense of empathy can be a helpful to see through the divisive ecology our ‘age of isms.’

(Rhetorical) Empathy in Our “Age of Isms”

“Empathy is the process of imaginatively entering into the personality of another in order to understand the way he interprets experience, to understand his beliefs, desires, fears, joys, sorrows – something that we can all do (…) ” – page 289.

“One way of explaining the process is to say that we come to understand the internal states of other people by first observing their behavior and then making inferences based on our memory of similar behavior of our own and of the internal states that produced our behavior” – page 289.

“Another explanation is that we imaginatively put ourselves into the shoes of another: in our minds we play the part of another, trying to see the world as the other person sees it and to respond to it as he responds.”- pages 289-290.

=> “As an exercise in understanding, select from a newspaper or magazine a letter to the editor that presents an argument with which you strongly disagree and try to empathize with its writer. Do you notice a change in your own attitudes toward the argument and the writer?” – Richard Young, Alton Becker, & Kenneth Pike, Rhetoric: Discovery & Change (1970): page 290.

Fig. 8. Texts from Dunn’s slide suggesting the strategies for “(Rhetorical) Empathy in our ‘Age of Isms’”

Discussion and Takeaway

One of the attendees in the session asked: “How would you recommend engaging and trying to combat propaganda?” She gave a poignant example of one of her friends’ parents who literally believed the propaganda coming from Russia that said Russia should be all and control everything and that Ukraine is being rescued. It is so pervasive that it separated the family.

In his response to the question, John Dunn acknowledges the gravity of the situation and suggests that attending to the classification can be helpful. He shares his own experience of asking question in another session on fake news and propaganda. His question was: how we make distinctions matters because labeling something as propaganda and fake news, we might lose some folks. He adds, thinking about a continuum or spectrum might make more sense in such a case. What is important, Dunn believed, is not saying one category or the other, but pointing out the intellectual moves taking place. For instance, there are some classifications involving the Ukraine crisis: Is it an invasion? Is it a resistance to oppression? When analyzing the available classifications or categorizations, Dunn would begin with the analysis part, not the point of disagreement. How does the person who speaks from Russian perspective see the world? Unpacking this question may reveal what they focus on and how narrow or specific part of the history they rely on to justify their support for Russia. After recognizing the focus, Dunn suggests, we may want to attend to the nature of the contrast—what exactly is different about Russia and Ukraine, Russia and the West?

As writing instructors, we often address such questions when we ask students to revise their writing by pointing out the things the student-writer has not mentioned or taken for granted. Helpful questions can be: Where does this contrast come from? Why are you making this? What are other options or alternatives? In line with Young, Becker and Pike, Dunn purports that rhetoric can play a necessary role to mediate when people feel strongly, and their opinions are passionate. We need resources to recognize what’s going on and think about the eventual way out or “how that is going to work out.” But that may take a long time.

The questioner chimes in with a follow up question: what if the people (like her friend’s parents) are following are purposefully gaslighting? Her friend’s parents moved to Russia to support Putin even though their other daughter, who was living in one of the cities being bombed, came to the US to escape the atrocities. In such a situation, is there any point in relating to other people who hold very dissimilar viewpoints? Dunn replies, “At the moment, No.” He saw the usefulness of Rogerian argument in such a tensed situation. The whole point of the Rogerian argument is to keep the dialogue going. At a given moment, when passions are high and events out there are tragic and people are denying truths, immediate breakthrough is not possible. Things may work out not today, not tomorrow, maybe not next year, but maybe five or ten years from now. Even though immediacy is very appealing in our kind of society, in terms of what is doable in a case like that of the questioner’s Ukrainian friend, there is bound to be a sort of stasis for the time being.

That is why Dunn reasons, it is important to tell students what is possible in terms of rhetoric. One argument does not change the world because it often gets ignored. However, multiple arguments over a longer period slowly shift people’s perspectives. Dunn’s suggestion is not to focus on an individual argument, but on shifting the worldview. Dunn points out that social movement rhetoric gives us a bigger perspective. He believes that a typical argument curriculum is a bit imaginary if one assumes that one argument is going to change everybody’s mind. It will not work that way. However, dozens and hundreds of arguments do. As instructors who are relatively more experienced than our writing students, we have seen a host of issues different now than they were a few years back. The idea of being able to help see where the changes in worldview come from goes back to Smith’s “illegeracy” concept.

Reviewer

Sarbagya Kafle