Overview

This presentation looked at Covid-19 teaching and its effects on teachers and students, with some clear take-aways about what Covid-19 teaching meant and continues to mean as we “return to normal” (whatever that might be).

Hybrid Strategies for Trauma-Informed Online Writing Instruction: A Course Design

- Kara Mae Brown, University of California Santa Barbara

Kara Mae Brown described her process of reworking an upper division, online writing class at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB), which focused on writing web content, to meet the needs of students who were, and are, experiencing trauma. After a quickly defining trauma-informed teaching and learning, Brown shared “Six Guiding Principles to A Trauma-Informed Approach” from SAMSA. As someone newish to this idea of teaching, it was comforting to read this list and realize that I, and most of the people I know in writing studies, do many of these things. But what Brown talked about next, made me realize how invested and engaged she was in this approach to teaching writing.

Brown mentioned how she had generally redesigned her classes by changing one or two things (a bit of teacher advice I was given three decades ago and have passed onto a couple of generations of teachers myself). However, this time around, Brown completely reworked and reconceptualized her class by moving to labor-based grading contracts, focusing on group work via blogs, and allowing an enormous amount of student choice in terms of how they approached the main assignments of the class. To get a fuller sense of this approach, I recommend that you read her clear and compelling presentation that was presented as a PowerPoint.

The result of this was a class that valued collaboration and individual work—with students doing individual work and teamwork, which she related to the project management idea of sprints (individual work) and scrums (group work). The presentation ended with a quote about the blog work by the student from some reflective writing, and a part of this quote that stayed with me was, “In the future, I won’t despise group work and opt to work independently. Instead, I will take that risk on collaboration because I realized how helpful and efficient it can be. These two skills-concise writing and a new love for collaboration-are the things I am most proud of about this blog project.”

A Lesson of COVID-19: Hybrid Instructional Modalities in Nepali Universities

- Raj Kumar Baral, The University of Texas at El Paso

Raj Kumar Baral reported on a study he conducted in Nepal about the rise of online/hybrid methodologies because of Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT), as well as the apparent after effects of this experience on 22 teachers and 66 students.

After a review of literature and a description of the survey that he administered, Baral laid out his results and conclusions. The most interesting of which were as follows:

- Students in the sample seemed to have to have managed to adapt to the context, but felt like they didn’t have as much interaction with teachers as normally.

- Somme teachers seemed to value learning new technical skills, which they hadn’t used in a classroom context before.

- Some teachers seemed to still appreciate face-to-face classrooms more

- Some teachers seemed to not have gotten the support that they wanted/needed in terms of learning new teaching technologies.

Ultimately, it was interesting to understand that many of the experiences I and others had during ERT were mirrored in Nepal, with some interesting difference. On the whole, Baral concluded that ERT was a time where students and teachers had “an opportunity to learn new technological skills” and that experience was “a lesson for accessible, inclusive, and resilient education, and gave birth to hybrid modalities in Nepali academia.”

Sense of Belonging: Mapping Out the Lived Transnational Experiences of International Students at US Universities During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Jianfen Chen, Purdue University

- Yao Yang, Purdue University

Jiangfen Chen and Yao Yang presented a very interesting study of “lived transnational experiences” of international students who attended “a highly-ranked public research university located in the Midwestern region of the United States.” Not only did Chen and Yao share their slide deck with the audience; they linked out to a whitepaper they wrote for the Center for Intercultural Learning, Mentorship, Assessment, and Research (CILMAR) at Purdue University, and this piece is worth reading.

The study itself was impressive in terms of methodology and its sample size. 103 students were surveyed and 21 interviewed; the sample itself skewed towards graduate students (82.86%) and students from Asian countries (73.53%). This is in no way a critique, particularly considering the national trend of students from China and India making up 53% of all of the international students; this means that the survey an interview data can, and should have, implications for most large R1, public universities.

What Cheng and Yang found was that international students in general did well emotionally and academically during the Covid-19 pandemic, and many, “felt a strong sense of belonging to the university and believed that they were valued and supported by the university.” However, they pointed out that, “a significant difference was found between high-achieving and non-high-achieving students in their perceptions of their school experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

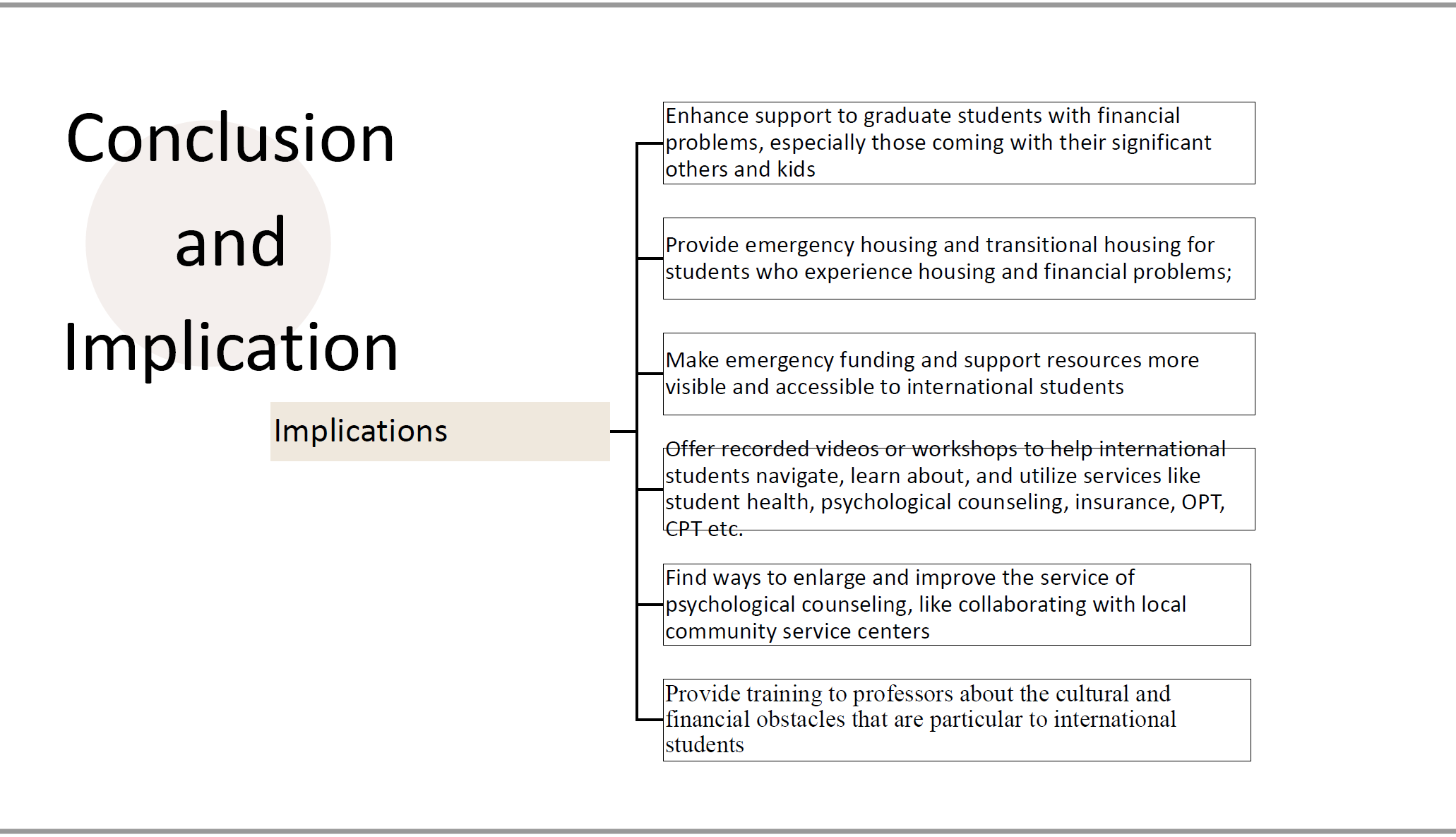

From these results they made a few recommendations, which you can see in the image below:

At the end of this presentation, I, as a teacher who works with many international students, was left thinking about how I might find ways to make clearer to my students that they can access resources, particularly financial resources that match their particular needs.

Takeaways

One of the interesting things about this presentation was its international focus, which resonated pretty deeply with me—as someone at an institution with a good number of international students. Chen and Yang, in particular, gave me (as you can see in the image above) a set of actionable ideas that could help me better serve my international students. Baral also made me consciously think about the Nepali academic context and the possible transnational lessons I could take from his research. Also, my colleague, Kara Mae Brown, helped me think about what a course redesign, with a focus on trauma-informed pedagogy might mean, and she even gave me a way of considering the way that I might think about collaborative and individual student work. All in all, I walked away thinking about my teaching (after 30-years as a teacher) in new ways.