During my formal education as an English and Portuguese language and literature undergraduate major in Brazil, I learned English through traditional methods like timed exams, grammar drills, and textbooks, and was mostly discouraged from using technology. This approach left me feeling inadequate, and I soon internalized that “writing in English was not for me.” Despite teaching English to Brazilians, I never felt confident in my written pieces in English.

Everything changed when I started volunteering at CAPA, the Academic Publishing Advisory Center— a writing center in southern Brazil where I acted as a translator and tutor, translating faculty and graduate students’ manuscripts from Portuguese into English. CAPA’s mission extended beyond publishing and internationalizing local research, as narrated by Martinez (2024). It emphasized the social nature of writing within an academic culture that often viewed it as an isolated act. Being a part of CAPA was challenging at first, but as I went through training sessions and as time went by, I started to feel more confident —most of our tutoring sessions addressed the act of writing even in Portuguese. Due to my translator role, I began to question my previous beliefs about writing and technology. Instead of viewing translation as a mere lexical equivalency, I started seeing it as a complex process of meaning-making across texts, modes, and disciplines. This eventually reflected positively beyond my role in the writing center but in my own writing.

Developing Critical Digital Literacies at the Writing Center…

Since there are multiple definitions of digital literacies (Tham et al., 2021) I draw on the Computers and Composition field to define what I mean by “critical digital literacies.” Thus, I echo Berry et al. (2012)’s understanding of digital literacies in their Transnational Literate Lives in Digital Times as simultaneously globalized and localized, as individual and social. I also resonate with Selber’s definitions of digital literacy, especially “functional” versus “critical” (Selber, 2004). These literacies involve understanding power dynamics, ethics, and socio-cultural impacts of digital technologies. In a world where digital communication is ubiquitous, being digitally literate means more than knowing how to operate technological tools, or what Watkins (2012) would consider tools literacy. It means thinking critically about how and why we use these tools and the broader implications of their use, or Watkins’ design literacy: “tools literacy is foundational; design literacy is transformational.” (Watkins, 2012, p. 9).

At CAPA, I learned that digital literacy goes beyond technical proficiency to encompass critical engagement with digital tools and platforms, and the meaning we make through the process. That is what I mean by Critical digital literacy in my narrative, and this understanding became the foundation for my development as a translator, as a tutor, and as a researcher.

… as a Translator

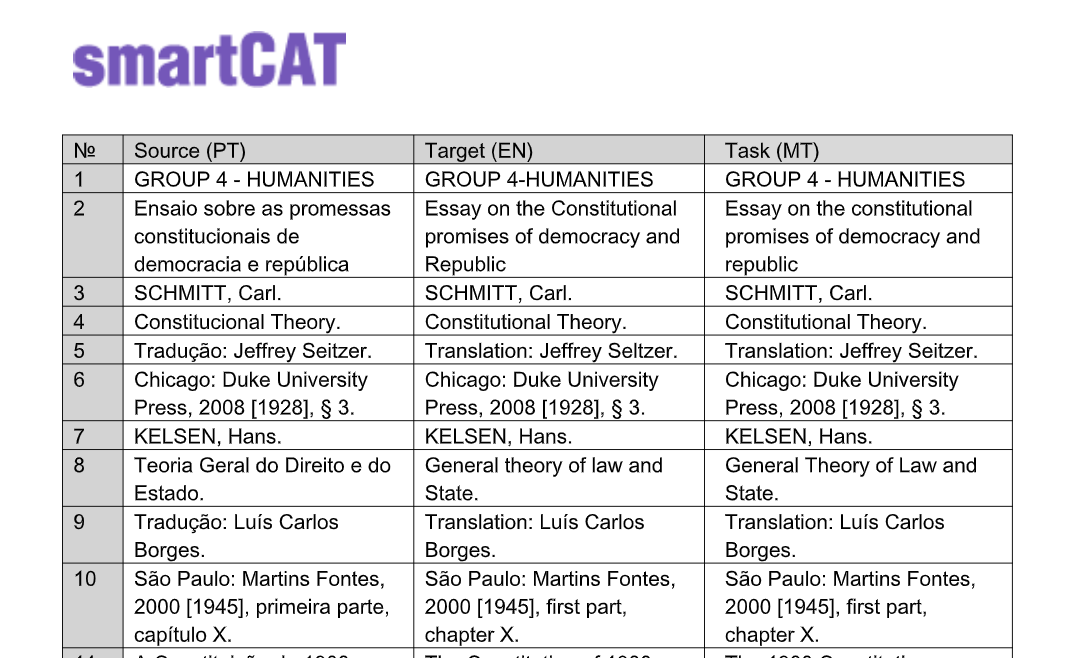

My time at CAPA was a masterclass in collaboration. Working in teams of 2-3 members, we used various platforms to facilitate our translation projects. SmartCAT, a Computer-Assisted Translation software, was our go-to software to collaborate in real-time and share files and translation memories for consistency. The platform had its multiple flaws, as any work tool, but it allowed us to think critically, mostly about embedded biases in the suggested translations.

Our weekly meetings stand out to me as the moments when I grew the most. In our groups, we had to discuss specific translation choices and argue why we believed a certain term or collocation would best serve us in that context. We grappled with our disagreements and tried to research specific disciplinary discourses and rhetorical moves that were common for a specific manuscript. The discomfort of negotiating and not finding an easy answer fascinated me in translation and later, reading about collaborative Multilingual Translation (Gonzales, 2022), I saw most of my concerns and experiences reflected in TPC scholarship.

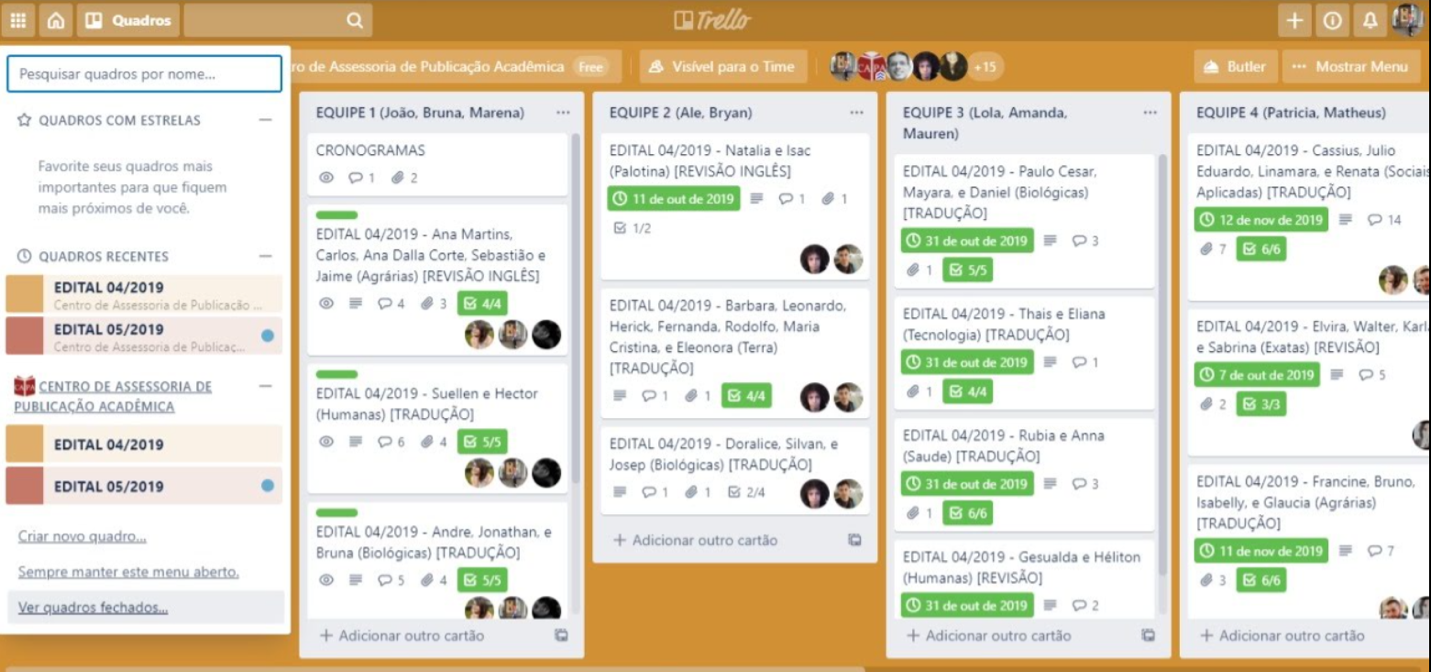

We also used AntConc, a corpus analysis software, to build glossaries and analyze language patterns; Google Docs facilitated real-time comments, edits, and collaboration, and Trello helped us organize and assign tasks, set deadlines, and manage our progress. I had to learn (and fail) on the job how to use each of those tools—some of them I use to this day. These experiences allowed me to open my own translation company and collaborate for 4 years with multiple authors before starting my PhD.

… as a Tutor

As a tutor at CAPA, I was introduced to the dialogue about writing—and that dialogue was always mediated through a screen, either in person or online. Working with students and faculty during our tutoring sessions, we discussed their manuscripts, made comments, and dealt with primarily digital genres such as emails, calls for proposals, journal articles, guidelines, and digital archives. I often used Google Docs to conduct collaborative writing sessions. This platform allowed for real-time feedback and editing, helping writers see the immediate impact of revisions and understand the collaborative nature of writing.

At CAPA, our tutor identities were based on acting as literacy brokers (Lillis & Curry, 2006), i. e., mediators of academic discourses. Considering how many of our writers had no writing-intensive courses or first-year composition training, the tutoring sessions were often the space to introduce essential digital tools and resources to the writing process. This included guiding them through library websites and databases, such as Google Scholar and Scielo, our predominant database in Latin America, in addition to institutional webpages, thesis and dissertations databases, and grant writing resources. For those writing in English, we would often recommend second-language glossaries, thesaurus and corpus tools like SkeLL for analyzing collocations. We also discussed digital genre conventions and adequacy, such as a draft of an email to an advisor or a Statement of Purpose for a study abroad fellowship. These sessions went beyond negotiating writers’ technical skills (or functional literacies), aiming to build their confidence in navigating digital resources and in the writing process.

… and as a Researcher

As I recently discussed elsewhere (Cons & Rezende, 2024), I believe the writing center should always encourage its members to become researchers. That belief comes from my personal experience since I carried out my Master’s research at CAPA with the support of our administrators. That is where I truly developed my critical digital literacies, or my design literacies according to Watkins’ framework. I learned to see the academic discourses and digital tools not as something detached from the individuals and practices at the writing center, but as intrinsically connected to the meaning-making of these communities.

In my current role as a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition, I frequently draw on research knowledge and platforms to conduct research, collaborate with colleagues, and communicate about the process. Even some of the qualitative software I have used in recent research projects, I have learned from a tutoring session. All my roles have been invaluable in helping me navigate these multiple identities and digital technologies thoughtfully and ethically, which ultimately culminated in my scholarly identity in the field of Writing Studies.

Implications and Lessons Learned

One key lesson for me from my time at CAPA was the importance of collaboration across the digital platforms. The ability to work in teams, communicate openly, and negotiate meanings in a collaborative project is transferable across multiple settings, not only in higher education but in other professional and personal contexts. Administrators should allow opportunities for tutors and writing center staff to collaborate organically and learn from the process with competent mediation.

Another key lesson is the value of critical thinking and ethical considerations in digital literacy practices. While wearing my translator, tutor, and researcher hats, I had to critically evaluate sources, engage with digital tools and platforms thoughtfully, and consider the ethical implications of my actions. In today’s context, where Generative AI is increasingly popular, these skills are more relevant than ever. We must dialogue and stimulate our writers to develop Critical AI Literacy (Gupta et al., 2022), encouraging them to critically engage with AI tools and understand their ethical implications.

Finally, the experiences at CAPA highlight the need for ongoing reflection and adaptation in our exponentially growing world of digital technologies. Since our realities are constantly changing, the ability to adapt and be critical in response to these changes is a key aspect of our roles and empowers our writers and members of our communities. As much as I initially felt that “writing in English was not for me” due to traditional drills and IELTS writing tasks, our writers might feel more encouraged if we teach them how to use Digital tools, including Generative AI, critically and ethically, rather than discouraging their use. This approach aligns with the development of digital literacy which is critical and inclusive.

References

Berry, P., Hawisher, G., & Selfe, C. (2012). Transnational literate lives in digital times. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press.

Cons, T. R., & Rezende, C. R. A. (2024). Brazil’s First Writing Center: Promoting Global Access and Enacting Local Change. The Peer Review, 8(1).

Gonzales, L. (2022). Designing Multilingual Experiences in Technical Communication. University Press of Colorado.

Gupta, A., Atef, Y., Mills, A., & Bali, M. (2024). Assistant, parrot, or colonizing loudspeaker? ChatGPT metaphors for developing critical AI Literacies. Open Praxis, 16(1), 37-53.

Lillis, T., & Curry, M. J. (2006). Professional academic writing by multilingual scholars: Interactions with literacy brokers in the production of English-medium texts. Written communication, 23(1), 3-35.

Martinez, R. (2024). The idea of a writing center in Brazil: A different beat. Writing Center Journal, 41(3), 9.

Selber, S. A. (2004). Multiliteracies for a digital age. SIU Press.

Tham, J. C. K., Burnham, K. D., Hocutt, D. L., Ranade, N., Misak, J., Duin, A. H., … & Campbell, J. L. (2021). Metaphors, mental models, and multiplicity: Understanding student perception of digital literacy. Computers and Composition, 59, 102628.

Watkins, S. C. (2012). Digital divide: Navigating the digital edge. International Journal of Learning and Media, 3(2).